Continuing the series on Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us by Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko. Previous post: How Terrorists… 1 – Personal Grievance.

This post looks at the psychological mechanisms at work among those who are radicalized and turn to terrorist acts in response to threats or harm inflicted on a group of cause they care about.

.

Vera Zazulich (alt Zasulich. Link is to Wikipedia article)

Nineteenth century Russia was a time of social turmoil. Vera Zazulich, from a modest noble family, became involved in student activist circles. She was arrested and exiled to a remote village in 1869 but returned to mix with a new student group.

Zasulich became outraged over an event she read about in the newspapers — the flogging of a political prisoner. The Governor of St Petersburg, Trepov, had passed the prisoner twice; the first time the prisoner removed his hat but not the second time. Trepov ordered him to be flogged. Zasulich did not know the prisoner, was not herself threatened in any way, but according to her own testimony at her trial she decided to risk her own life to follow her conscience and attempt deliver justice upon cruel government officials for their mistreatment of student activists. (Zasulich had planned with a friend to kill two government officials and drew lots to decide their respective targets.)

Their motivation was to see justice done. It was entirely altruistic. They had nothing to gain; Zasulich was acting on behalf of people she did not know against others she did not know personally. Her actions and testimony following her crime (she did not attempt to hide and said she was prepared to face any penalty the court decided) make it clear that she had nothing to gain for herself.

.

Theodore Kaczynski (the Unabomber)

Kaczynski gave up his academic position at the University of California and sought to punish those he believed were leading social technological-industrial changes that denied the needs of human nature and were harmful to humanity.

Again, he had nothing to gain and was acting on behalf of others when he sent bombs that killed three and wounded twenty-three.

Kaczynski’s ideas drew on critics of the twentieth century’s Brave New World.

.

John Allen Muhammad (the Washington sniper)

According to his accomplice, Muhammad (a Gulf War veteran and “a convert to Islam and black separatism”) who shot dead ten people and wounded two

hoped to extort several million dollars from the U.S. government and use the money to found a pure black community in Canada. Muhammad was not forthcoming about the origins of this plan, but it appears that he reacted to what he saw as the victimization of black people in the United States.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 527-529). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Muhammad’s political ideas appear to have been related to his time in the Nation of Islam.

.

In 1999 Waagner admitted to police he was planning on murder abortion providers with the illegal firearms found in his car. (As a convicted felon — theft, burglary, attempted robbery — he was forbidden from possessing firearms.) After escaping from prison he sent hundreds of letters as anthrax hoaxes to abortion clinics causing many to shut down. The criminal activities “showed planfulness bordering on genius”.

Clayton Waagner may have begun as a petty criminal, but he ended with what he saw as a God-given mission to make war on those “who make war on the unborn.”

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 545-546). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Waagner’s (attempted/threatened) political violence appears to have been fueled through web sites of antiabortion groups such as the Army of God.

.

Though acting as “lone-wolf terrorists” they nonetheless had connections with wider political ideas. But among “lone wolves” there is a higher chance of psychopathology being a factor in their actions. Kaczynski was said to have suffered from paranoid schizophrenia. (More recently the Sydney hostage-taker, Man Haron Monis, has been associated with mental disorder.)

Not all such terrorists are acting out their inner demons, however. Vera Zasulich, John Allen Muhammad and Clayton Waagner had no signs of mental problems.

.

Altruism and Strong Reciprocity

Humans are among the more social animals that experience the clear benefits of group cooperation. McCauley and Moskalenko [M&M] remind us of the classical example of the hunter who shares his catch today in the expectation that when he is less lucky others will share their food with him.

The problem is that there are always cheaters. If cheaters succeed then others are likely to follow and eventually all cooperation ceases. What keeps the cooperative life of the group alive is the presence of members who are willing to punish the cheaters.

A group can reap the benefits of altruism if it has members willing to carry out justice at a price to themselves. Altruism can succeed if there are enough individuals who respond in kind—tit-for-tat—to both cooperation and cheating. Strong reciprocity describes this combination of two tendencies, to cooperate and to punish. The combination can be successful where the tendency to cooperate, taken alone, would disappear under the costs of cheaters.

Psychologists use various games such as variants of the Prisoner’s Dilemma to study this attribute among humans.

In some PD [Prisoner Dilemma] games, participants are offered a chance to use some of their own winnings in order to “punish” defectors—paying to reduce the payment to those who do not reciprocate cooperation. . . .

Results of PD games show that most individuals begin by trying to cooperate and that most individuals are ready to pay extra to punish those who do not cooperate. Importantly, it is not just those who suffer the defection who are ready to pay to punish the defector. A third party is often willing to pay to punish a defector despite the fact that the one punishing did not suffer personally any loss to the defector. Not only will we pay to punish those who spit on us in response to our kindness, we will even pay to punish those who spit on others. Even in these simple games, then, individuals are willing to pay personal costs to punish bad behavior that does not affect them personally.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 579-587). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition. — My own bolding in all quotations.

The findings are cross-cultural. M&M tell us that in tests across many cultures 40% to 60% of game players are willing to pay to punish defectors.

Zasulich is a clear illustration of a third party willing to pay a cost to carry out justice for her group.

If we are ready to generalize from bad individuals to bad groups—a projection not yet studied in the game theory literature—then Muhammad and Waagner can also be seen as extreme examples of individuals incurring personal costs to punish perceived malefactors.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 590-592). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Presumably the number of people willing to pay a price to punish others depends upon the price required. The higher the cost required to carry out justice the fewer there would be willing to pay.

There is another way to understand third-party punishments.

Group Identification

Identification with another means caring about the other person’s welfare. Positive identification means we feel good when the other is safe, prospering, or growing, but we feel bad when the other is in danger, failing, or diminished. Negative identification is an inverse concern for the welfare of another: negative identification means we feel good when the other is in trouble, and we feel bad when the other is safe and prospering.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 598-601). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

M&M’s examples of positive group identification (our caring about groups we are not a part of) include:

- causes for Tibet’s welfare

- deep interest in popular entertainers (I’d add the royal family)

- sporting teams

- fictional characters

- companion animals

In all of these cases, our concern for the welfare of the other goes beyond any economic value to the self. That is, our own material welfare is not significantly improved by raising the welfare of Tibetans, Britney Spears, the Dallas Cowboys, Tiny Tim, Hero, or Shoesy. Nevertheless we invest real money, real time, real anxiety, real tears, real pride, and real joy in the ups and downs of others whom we care about. And when what we care about is threatened, conflict is likely to ensue.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 604-607). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

People are quite capable of making real sacrifices for groups we identify with. Most people will feel sympathy when their group interest is harmed but there are some who are willing to sacrifice their own self-interests for the other, and the higher the sacrifice the fewer there will be — but they are found. Of the many who sympathized with the student who refused to raise his hat to the governor only two (Zasulich and her friend) were willing to sacrifice their lives to see justice done. Many feel exasperated over the plight of African Americans but there has only been one John Muhammad. Many view abortion as murder, but not many Clayton Waagners have emerged.

Why only these three — Zasulich, Muhammad and Waagner? Is there a common personality type? Not likely: we have “a tender-hearted secretary, a macho ex-soldier, and a criminal turned crusader”.

Our three examples of normal individuals turning to radical individual action for a cause suggest the difficulty of specifying a personality predictor or profile for this rare form of radicalization. We turn now to try the relevance of our analysis for a modern example of radicalization by political grievance.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 620-622). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

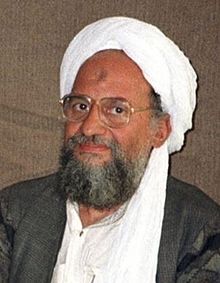

Ayman Al-Zawahiri — from Intellectual to Terrorist

Ayman Al-Zawahiri (Link to Wikipedia)

Look first at the Egyptian family from which Ayman came

| Father’s side of his family | Mother’s side |

| The more scholarly . . . | The richer and more political . . . |

| Father (Dr Mohammad Rabie al-Zawahiri) was a professor of pharmacology | Mother (Umayma Azzam) had a great uncle married to daughter of Libyan resistance leader who had fought against the Italians |

| Uncle a dermatologist | Great uncle became first secretary-general of Arab League, given title of Pasha by Egyptian government |

| More than two dozen physicians, chemists or pharmacists | Her father studied in London; became dean of School of Literature at Cairo University |

| More than forty physicians counting relations by descent and marriage | Father later was ambassador to Saudi Arabia and Pakistan |

| Despite the above tradition in medicine, the family was more famous for its religious scholars — one was rector of Al-Azhar University, the most prestigious post in the most prestigious centre of Islamic learning in the world. | Father became first administrator of Riyadh University in Saudi Arabia |

.

Ayman was strongly influenced by his maternal uncle, Mahfouz Azzam.

The following biographical notes lead us to explore the dynamics of personal grievance and political motives/group grievance coming together.

- 1936, Mahfouz Azzam, in third grade, was taught Arabic by Sayyid Qutb. The two formed a close and lasting bond.

- After one stretch in jail Qutb published Milestones, “which remains today an inspiration for those Muslims who would replace secular government with an Islamic state.”

- Egypt Government condemned Qutb to death for Milestones

- 1966, Mahfouz had become Qutb’s lawyer and visited Qutb just before his execution. Qutb gave Mahfouz “a martyr’s parting gift” of his inscribed copy of the Koran.

- Ayman was fifteen years old at the time.

From Qutb to Mahfouz and from Mahfouz to Ayman came a radical critique of the Egyptian government as hopelessly corrupt and a radical alternative in the purity of government by Sharia. Along with the radical vision came a radicalizing personal experience of suffering at the hands of the government. The government had twice jailed Ayman’s uncle and had jailed, tortured, and finally executed his uncle’s dearest friend and mentor.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 641-644). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Ayman himself was not naturally inclined to leading the life of a political protestor, being described as a child as “religious, bookish, a lover of poetry, and uninterested in sports.”

In the year Qutb was executed (1966, Ayman being 15 years old) Ayman helped to form an underground cell to spread Qutb’s ideas.

In the 1970s his cell joined with several others to form Jamaat al-Jihad.

Ayman completed his medical studies; served as a surgeon in the Egyptian Army for three years; opened his own clinic; married; worked for the Red Crescent in Pakistan to treat refugees from from the Russian conflict in Afghanistan. . . . returned to an Egypt in turmoil. . . .

1979, an Islamic state was established in Iran. This was what Qutb had hoped to see and what Ayman had hoped to see in Egypt.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat responded by banning and jailing many Islamic groups. A military cell within Jamaat al-Jihad assassinated Sadat. Ayman was among those subsequently arrested by Sadat’s successor, Mubarak.

The common fate of suspected conspirators in Egyptian prisons was humiliation and torture. By several accounts Ayman broke under torture and cooperated with security forces in a trap set for Essam al-Qamari, a charismatic Army officer who had planned with Ayman to bring down the government with a bomb attack on Sadat’s funeral. In his memoir, Knights under the Banner of the Prophet, Ayman was probably referring to his own experience in this passage: “The toughest thing about captivity is forcing the mujahid, under the force of torture, to confess about his colleagues, to destroy his movement with his own hands, and offer his and his colleagues’ secrets to the enemy.”

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 657-661). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Ayman al-Zawahiri left prison “a hardened extremist for whom death was not horror but release.” Earlier he had grieved over the hurt to loved ones, his uncle and his uncle’s friend Qutb, and now he had suffered physically as well as suffering the humiliation of having betrayed a friend. He looked back on his years with al-Jihad as amateurish and bungling.

Ayman al-Zawahiri left prison with these personal grievances framed as part of a larger victimization of devout Muslims, that is, with a sense of grievance that integrated revenge with jihad.

Synergism of Personal and Group Grievance

In the case studies we have seen so far the personal and group grievance are very often found together.

Radicalization seems to happen when the two grievances combine.

We saw in the previous post that the personal grievances of Zhelyabov and Amara soon directed their hostility towards landowners in general (not just the one responsible for the rape of his aunt or those who facilitated in the ensuing injustice) and towards all expressions of racism (not only towards certain racist police). They acted not just for an aunt or a mother, but for serfs in general and for all Muslim immigrant women. Their personal grievances became politicized.

Zasulich and Waagner also had personally experienced the prison and justice systems they later came to despise and with which they had lost all confidence to deliver true justice.

The blending of personal and political is most pronounced in the case of al-Zawahiri. He hears first about the suffering of his uncle and his uncle’s mentor Qutb at the hands of the Egyptian government, but from the very beginning their experience is interpreted for him as the suffering of devout Muslims trying to replace secular injustice with Sharia justice. After Qutb is hanged, Zawahiri’s antigovernment activity brings him up-close and personal experience of the victimization of Islamists in Egyptian prisons. He leaves prison a hardened terrorist, as ready to accept death as to mete out death to the enemy.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 681-685). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Making sense of the anger lasting only minutes but the planning going on for years

We can now further begin to understand the paradox of, on the one hand, grievances producing strong emotions that according to psychological research last only minutes, while on the other, the actions of revenge and justice that are stimulated by those transient emotions are planned over weeks or years.

To the extent that grievance depends on identification, however, it can be steadier than the vagaries of strong emotion.

An individual is usually radicalized when there is a blending of personal and group grievances.

Personal tends to mean that one has a negative identification with the group seen as the perpetrator of injustice and a positive identification with the group seen as the victims of injustice.

These reciprocal positive and negative identifications provide stable incentives for intergroup conflict, as successes of the positive-identification group are rewarding and successes of the negative-identification group are punishing.

The stability of group identifications can explain the stability of intergroup conflict, revenge, and justice-seeking despite the brevity of emotions of anger and outrage.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 697-700). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Is there then “a predictor for this rare form of radicalization”? If so, M&M suggest it is to be found in those who feel the most strongly for a group or cause. Studies in altruism have demonstrated the importance of sympathy and empathy in predicting help for a stranger in distress. That’s not the same as predicting aggression towards the one responsible for the stranger’s distress, but it would seem to follow.

If both personality and personal experience are necessary for lone-wolf terrorism, then attempts to profile this combination must face considerable complexity. Although it offers no easy answers for security services concerned with lone-wolf terrorism, our perspective is consistent with a well-established finding in psychological research: individual behavior depends, not separately on person or situation, but on their interaction.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 712-715). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

.

Next, Slippery Slope. . . .

.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I’d like to thank Neil Godfrey for this excellent series on a historical and biographical and psychological look at the makings of terrorist extremism. I find they have begun to help me think through and grasp a little more clearly my own reading on the subject. This second post is perhaps a little amateurish but in a discussion on another forum I did have cause to reflect upon the main theme being presented here and the argument became a lot clearer in my mind. As Chomsky and probably others, too, have said, we don’t really know what we’re thinking until we write it down or say it.

If we are asked in the above case studies what role religious beliefs played in causing terrorism, we’d be forced to take a step back and reconsider the whole study. Beliefs in a better or more moral way of life were at the upper consciousness of all those cited here — from wanting a more just secular society, to wanting a more just approach to the unborn, to wanting a more natural and free existence, to wanting a more holy life — all opposed to injustice, cruelty, etc.

We don’t all agree on the specific visions in each case, but we all do share the vision of a better society and are opposed to the “systematic injustices” that stand in the way of it. (Or most or many of us probably do.)

So the question is why do only a few, such a tiny few, turn to extremist violence in these causes? For some people, for a tiny few, we have seen what those factors can be. Can we really blame the vision itself for the violence? The answer is in the post. Many, for example, do believe abortion is murder. Some even speak of a holocaust. But only a handful…..

“Synergism of Personal and Group Grievance”

very interesting—–

…many years ago, a look at Irish terrorism had come to a similar conclusion…If I remember correctly……