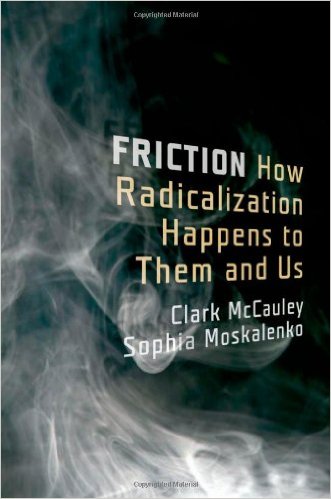

Not every book I discuss here I would recommend but I am about to post on chapters in Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us by Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko and this one I do recommend. It is a quick yet grounded introduction to a range of factors that turn people towards radical action against state powers, extremist violence and terrorism. Each chapter looks at one of twelve contributing factors through biographical case studies accompanied by descriptions of scientific research into the relevant human behaviour.

Not every book I discuss here I would recommend but I am about to post on chapters in Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us by Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko and this one I do recommend. It is a quick yet grounded introduction to a range of factors that turn people towards radical action against state powers, extremist violence and terrorism. Each chapter looks at one of twelve contributing factors through biographical case studies accompanied by descriptions of scientific research into the relevant human behaviour.

Some of the mechanisms for radicalization operate at an individual level; others involve the dynamics of small group and mass social psychology.

Not only do we read about “them” but we also learn what motivates “us” to fully support our governments to launch campaigns of state terrorism — war, torture, extra-judicial murder.

Sometimes it appears just one factor is enough to propel people to extremist violence; more often several factors come into play. Friction concludes with a look at the life of Osama bin Laden to demonstrate how a range of triggers and conditions coalesced in one person to lead to 9/11.

The message conveyed is that there is rarely a single simple explanation for why people become involved in extremist violence and terrorism.

Over the next several weeks/months I hope to address each of the twelve dynamics covered by McCauley and Moskalenko. The table below lists the topics to be covered.

| Type of mechanism | Mechanism | Case studies |

| Individual | Personal Grievance | Andrei Zhelyabov Fadela Amara |

| Individual | Group Grievance | Vera Zazulich Theodore Kaczynski (Unabomber) John Allen Muhammad (Washington sniper) Clayton Waagner (abortion providers) Ayman Al-Zawahiri Bin Laden |

| Individual | Slippery Slope | Adrian Michailov Omar Hammami (Abu Mansoor Al-Amriki) Bin Laden |

| Individual | Love | Sophia (Sonia) Perovskaya & Andrei Zhelyabov Amrozi bin Nurhasyim (smiling terrorist) Bin Laden |

| Individual | Risk and Status | Alexander Barannikov Leon Mirsky Ahmad Fadeel al-Nazal (Abu-Musab al-Zarqawi) Bin Laden |

| Individual | Unfreezing | Sophia Andreevna Ivanova (Vanechka) Muhammad Bouyeri |

| Group | Group Polarization | |

| Group | Group Competition | |

| Group | Group Isolation | |

| Mass | Jutitsu Politics | |

| Mass | Hatred | |

| Mass | Martyrdom |

.

Personal Grievance

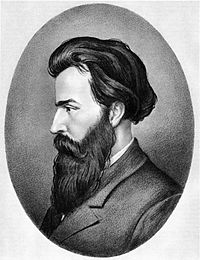

Andrei Zhelyabov (link is to Wikipedia article where the political careers of each person can be read. I won’t repeat the details here.)

Zhelyabov wanted revenge against the landowner who had raped his aunt; later, when local landowners blocked the case against the rapist, he wanted revenge against landowners as a class. His life as a terrorist can be understood as motivated by a powerful confluence of personal revenge with abstract ideas of justice for serfs that were held by many university students.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 368-371). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

.

Fadela Amara (not a terrorist but a radicalized Muslim — showing that personal grievance leading to political radicalization does not have to lead to violence)

Amara, [a Muslim] reacts first to victimization of her mother, but soon the target of her hostility is expanded from racist policemen to anyone—including immigrant men—who disrespects immigrant women, and her identification with her mother expanded to identification with the welfare of all Muslim immigrant women.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 674-676). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Zhelyabov (nineteenth century Russia) and Amara (twentieth/twenty first century France) turned personal grievances into broader political action. The former faced government repression and turned to terrorist tactics. The latter engaged in illegal activity but without state repression she was able to transition her radical opposition into a successful political career. Radicalization does not necessarily lead to violence.

Why do some people turn their personal grievance into a political cause against an entire group on behalf of another group?

Contrast, for example, the 9/11 terrorists with Joseph Stack.

In contrast, there are occasions in which a personal grievance stays personal, and the victim acts for revenge against a particular perpetrator. In February 2010, Joseph Stack, a 53-year-old software engineer, flew his Piper Cherokee into an IRS office building in Austin, Texas. He left behind a manifesto detailing his anger against the IRS . . There was no obvious positive identification with a group of similar victims, and the personal did not become political as it had for Zhelyabov and Amara.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 433-434). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

.

Mass radicalization from personal grievance:

The experience is not limited to individuals. Nineteen Arab Muslims caused many of us to turn in anger against all Arabs and Muslims.

A Western democracy, proud of its tradition of personal freedoms and human rights, has a history of international interventions to restore peace and stop atrocities. One day ethnic fanatics attack the country’s largest city, killing or injuring thousands. Shock and disbelief evolve into grief and outrage. Hundreds of ethnic immigrants are rounded up on suspicion of being related to the attack, and are detained without access to the legal system. To get information from individuals suspected of militant activities, the government issues a secret mandate to torture them. The government’s violations of internationally recognized standards of human rights are exposed by the media. Nevertheless, the government is reelected by a majority of its citizens.

This transition took place in the United States after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Americans embraced the unthinkable in search of retribution and security. We were radicalized: our feelings, beliefs, and behaviors all moved toward increased support for violence against perceived enemies, including sometimes Arab and Muslim Americans. We idealized American values, gave increased power to American leaders, and became more ready to punish anyone seen as challenging patriotic norms. More generally, radicalization is the development of beliefs, feelings, and actions in support of any group or cause in conflict.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 146-156). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

.

To understand why some people turn a personal grievance against one or a few persons into a hostility against an entire class of people on behalf or another class of people

we need a theory that describe when and how individual events are interpreted in terms of social conflict between groups.

Moreover, emotional heat is transitory, as psychologists know. Political action on behalf of “abstract categories of people”, on the other hand, can be undertaken over many years. So how can short term emotions over personal grievance explain long-term actions against classes of people for the benefit of other classes?

The psychological mechanisms that change some people’s outrage over a personal offence into political action for a wider interest are explored in the next chapter of Friction dealing with group grievance.

The next post is now published at How Terrorists Are Made: Part 2, Group Grievance

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

So pleased that you’re finding this recommendation so rewarding – it’s a highly informative, accessible and succint book. Really great. And it’s reading things like ‘Friction’ that makes me pull my hair out when there’s another conversation about extremist behaviour and someone simply bangs on about beliefs – there’s so much more, and much more interesting, stuff to be talking about. Yet it’s so hard to convince people who HAVEN’T read this stuff that they’d do well to do so. What’s so massively galling is that these people often seem completely unmotivated to engage with works like ‘Friction’. I cannot understand it. But it’s deeply annoying.

On a less negative note, I think bringing the ideas and arguments of ‘Friction’ to your readers is a great thing to do – hope you get the appreciation you deserve for performing this service.

[This is just for Neil: And finally, Scott Atran unfortunately couldn’t make it to the conference I went to in Oxford on ‘Going To Extremes’ (and where I spoke about identity fusion) as he was ill – but there were lots of other fascinating speakers, and I came away buzzing with thoughts. It was noteworthy that the kinds of ideas peddled by Harris and Coyne were nowhere to be heard, in any corner or from any mouth. As you might expect from a group of experts, it was all a bit more complicated.]

Dan, was there a recording of the conference you went to that we can listen/watch? Thanks.

Unfortunately not. I was going to film the event, but it was too much to be a speaker and attendee as well as videographer. There are plans, however, for people to write up their talks for publication. I’ll keep Neil posted, and maybe he can link to any resulting papers in the future. In the meantime, you can find out more about identity fusion, the topic of my talk, in these papers by Bill Swann, who developed the idea:

http://homepage.psy.utexas.edu/homepage/faculty/swann/docu/swann-buhrmester%20Current%20Directions%20.pdf

And

http://homepage.psy.utexas.edu/homepage/faculty/swann/docu/buhr-swann,emerging%20trends.pdf

Thanks for the links Dan, I don’t have much knowledge in this area but it does intrigue me, so it would be nice if you and Neilk could keep us updated.

“We were radicalized: our feelings, beliefs, and behaviors all moved toward increased support for violence against perceived enemies, including sometimes Arab and Muslim Americans.”

-Is there any evidence at all for this? I recall polls generally showing an increase in positive feelings towards Muslim Americans in the aftermath of 9/11.

What was rightly observed by many commentators at the time was that much of the world had an immediate sympathy with America but that that sympathy was lost when the US responded with its own terror campaign of war in retaliation.

Really, that’s your recollection? In 2002, “The FBI’s annual hate crimes report found that incidents targeting people, institutions and businesses identified with the Islamic faith increased from 28 in 2000 to 481 in 2001 – a jump of 1,600 percent. Muslims previously had been among the least-targeted religious groups.” There is a caveat to these statistics: “The statistics did not specify how many of the 481 occurred after Sept. 11, 2001.” I wish the report had spelled this out. However, the idea that the worst attack on America since Pearl Harbor, carried out by Muslims, had nothing to do with a 1,600% rise in anti-Muslim hate crimes stretches credulity. And today anti-Muslim hate crimes

And also, you may recall that after 9/11, the US and coalition forces invaded Iraq, then Afghanistan. The terror attacks and the foreign policy decisions were not unconnected. You don’t have to be Noam Chomsky to think that maybe these were quite extreme reactions to what was, undoubtedly, a tragedy that shook the psyche of the nation. In fact, it seems like the psychological shock of 9/11, more than the facts on the ground, is what influenced these disastrous foreign policy decisions.

One final thing: do you post quite frequently over at Why Evolution Is True? I thought I recognized your name, and I see from your blog that you like at least some of Coyne’s post (notably a one showing how everything bad in America is correlated with religion). I also see that you’re a big Sam Harris fan, describing him as “one the finest anti-religious authors of our generation”, so I can’t imagine you’re going to be very receptive to the discussions being held here. Perhaps that explains why your comments are so oddly focused on very small points, and ignore the larger point of the posts you’re ostensibly replying to. Neil has written an interesting post on a fascinating book, but instead of engaging with this, you come back with …. well, what you came back with! Way to look parochial…

-Where’d I do that? I might have done so, but I can’t find it on Google. I post occasionally on WEIT, not very frequently. I do, indeed, admire Jerry Coyne’s necessary corrective to the anti-atheist bias prevailing in the media, and I consider him to be a great advocate for atheism. I like most of his posts.

Your points aren’t inconsistent with my claim. American opinion regarding Muslim-Americans in the aftermath of 9/11 became generally more polarized -both negative and positive opinions towards Muslim Americans became stronger.

“And today anti-Muslim hate crimes”

-???

“And also, you may recall that after 9/11, the US and coalition forces invaded Iraq, then Afghanistan.”

-Uh, no, it was Afghanistan, then Iraq.

“In fact, it seems like the psychological shock of 9/11, more than the facts on the ground, is what influenced these disastrous foreign policy decisions.”

-Maybe so, but I don’t think the Saddam-9/11 connection hysteria ever reached the most informed part of the populace.

Doh, you’re right to pick me up on my silly Iraq-Afghanistan switcheroo – that is a bit embarrassing! And also I left a sentence hanging (thought I’d deleted it – the perils of dashing off things in a hurry). Re: the Harris assessment I ascribed to you, it’s the roll-over description you gave for him when he’s listed on your roll-call of blogs you like. But look, we’re getting into stuff that’s irrelevant to me really, so I’m out.

Found the evidence!

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/06/03/ratings-of-muslims-in-france-and-us/

“Justice is conscience, not a personal conscience but the conscience of the whole of humanity. Those who clearly recognize the voice of their own conscience usually recognize also the voice of justice. ”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

To seek justice is admirable–even noble—but Justice that is not balanced by compassion and mercy leads to injustice….