In foreign policy, the United States — especially in the last hundred years or so — has tried to have it both ways: assiduously following the Constitution and domestic law, as well as keeping within the dictates of international agreements, while at the same time aggressively maintaining an empire with far-reaching hegemony. In doing so, the executive branch often finds itself carrying out actions that conform to the letter of the law, but would seem to violate its spirit.

The Duck Test

War and diplomacy, domains in which precision in word choice matters, are fertile grounds for Newspeak. Consider, for example, the frequent use of the words “conflict” and “police action” after World War II. The U.S. government has tended to avoid the word “war,” because it has a definite meaning, a specific basis in law. For the U.S., it means that Congress has approved a formal declaration of war against another sovereign state or group of states. The new terms play a role in American “freedom of action” (viz., the use of violence and the constant threat of violence to advance policy) while apparently staying within the boundaries of the law.

Consider, as well, President John F. Kennedy‘s use of the term “quarantine” during the Cuban Missile Crisis, deftly avoiding the word “blockade,” which is a legal term that signifies an act of war. The administration called it a quarantine for diplomatic purposes; however for the purpose of exercising power, it did the job equally well. It quacked like a duck and walked like a duck, but calling it a duck might have precipitated World War III. (As it was, we were closer to doomsday than we realized.)

Finally, consider the terms “detainee” and “unlawful combatant” as used by American administrations in the wars that followed the September 11 terror attacks on U.S. soil. “Prisoners of war” have a distinct status in international law, and all signatories to the Geneva Conventions have agreed to treat those prisoners according to a detailed set of protocols. Yet the Bush administration said that despite the all the quacking and the cloud of feathers, those waddling birds were not ducks.

Terms of Art

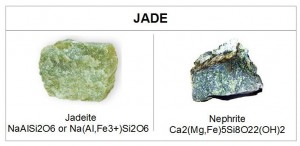

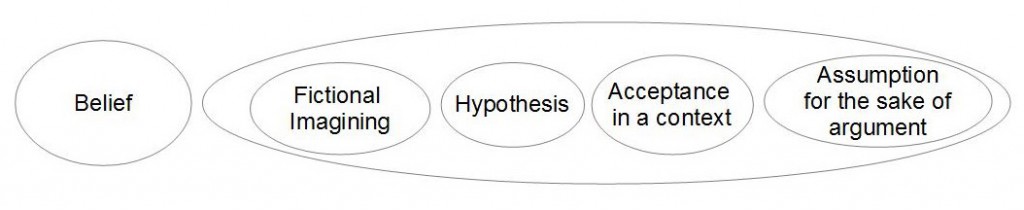

In the social sciences as well, we have terms of art that refer to specifically defined concepts, conditions, events, etc. It drives experts in psychology, well, a bit mad when authors in popular media incorrectly use terms like schizophrenia. Notice that I deliberately avoided the word “insane,” since that’s a term of art in both the clinic and the courtroom. It is especially important when writing about a particular subject matter to use terms of art only for their intended purpose. Moreover, if you (unadvisedly) choose to redefine a well-established term of art, then you should clearly state what you’re doing up front.

The realm of memory theory, including the psychological study of personal memory and the sociological study of group memory, has its own terms of art. I offer the following examples.

- False memory

- Counter-memory

I present these two here because I have lately seen Memory Mavens misuse them in the similar ways. Specifically, they incorrectly use a term of art to describe a general condition or event. Doing so muddies the water; it confuses the experts who know how the term ought to be used, and it misinforms the general public who trust scholars and expect them to know what they’re writing about. Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 7: When Terms Matter”