Earl Doherty and Richard Carrier have suggested that there is an ancient text outside the Bible that stands as direct evidence for some early Christians believing Asc. Isa.), believed to be a composite document whose earliest parts were quite likely authored as early as the late first century.

Scholarly work on Asc. Isa. has been on the move. 1995 saw two pivotal Italian works that have paved the way for a new consensus. Enrico Norelli has been a key player in this research.

- Ascensio Isaiae: Textus, ed. P. Bettiolo, A. Giambelluca Kossova, E. Norelli, and L. Perrone (CCSA, 7; Turnhout, 1995);

- E. Norelli, Ascensio Isaiae: Commentarius (CCSA, 8; Turnhout, 1995).

These were both included in volumes 7 and 8 of the Corpus Christianorum Series Apocryphorum in 1995.

I don’t have access to those but yesterday a copy of Norelli’s 1993 Ascension du prophète Isaïe arrived in the mail.

I have only struggled through chapter 2 with my very rusty French so far but it is already clear that the old views are being challenged.

Here are the highlights:

- The work is not nearly so fragmented as earlier studies have believed. Both the first part, chapters 1 to 5, depicting the martyrdom of Isaiah, and the second part, chapters 6 to 11, portraying Isaiah’s vision of the descent of the Christ figure (the Beloved) down through the seven heavens to be crucified, harrow hell and return to sit beside God again, are Christian works.

- The Christian sect responsible for the Asc. Isa. (all of it) was exalted revelations through visions and saw themselves competing with rival sects, each blaming and persecuting the other as false prophets.

- The account of the birth of the Beloved to Mary in Bethlehem is not a late addition but was original to the vision chapters (6-11). That means The Beloved did indeed descend to earth and was crucified on earth — unrecognized by the demons.

- The details of the nativity scene draw on a source also known to the evangelist responsible for the Gospel of Matthew. The Asc. Isa. does not know the canonical gospel but both are using a common source. The two nativity versions — Matthew’s and the Asc. Isa.‘s — represent competing theologies. That is, the Asc. Isa. was (and several reasons are given for this conclusion) written around the same time or environment that produced the Gospel of Matthew.

- The reason for the Beloved appearing to be flesh and dying was to save humanity by means of conquering their demonic rulers.

To me this is fairly mind-blowing stuff if true. We would need to account for a view of the “gospel” that stood in stark contrast to all the assumptions and “traditions” behind Matthew appearing on the scene at around the same time. That question alone poses enormous questions for the traditional view of gospel origins, surely.

Further, if we accept Norelli’s revisions to our understanding of the Asc. Isa. then it would appear that the Asc. Isa. might support in part Roger Parvus’s interpretation of the original (“mythicist”) gospel: that Jesus descended to earth to be crucified before ascending again. Except that Roger, I think, argued for Christ only appearing for a short time on earth for this purpose. The Asc. Isa. has the Beloved hiding his identity from the demons by means of slipping into the world through Mary.

Okay, my head is still spinning. Keep in mind that the above is my impression as discerned through some very fuzzy memories of my French. I would like to roughly paraphrase (not translate!) the different sections of chapter 2 to share with others here over the coming weeks.

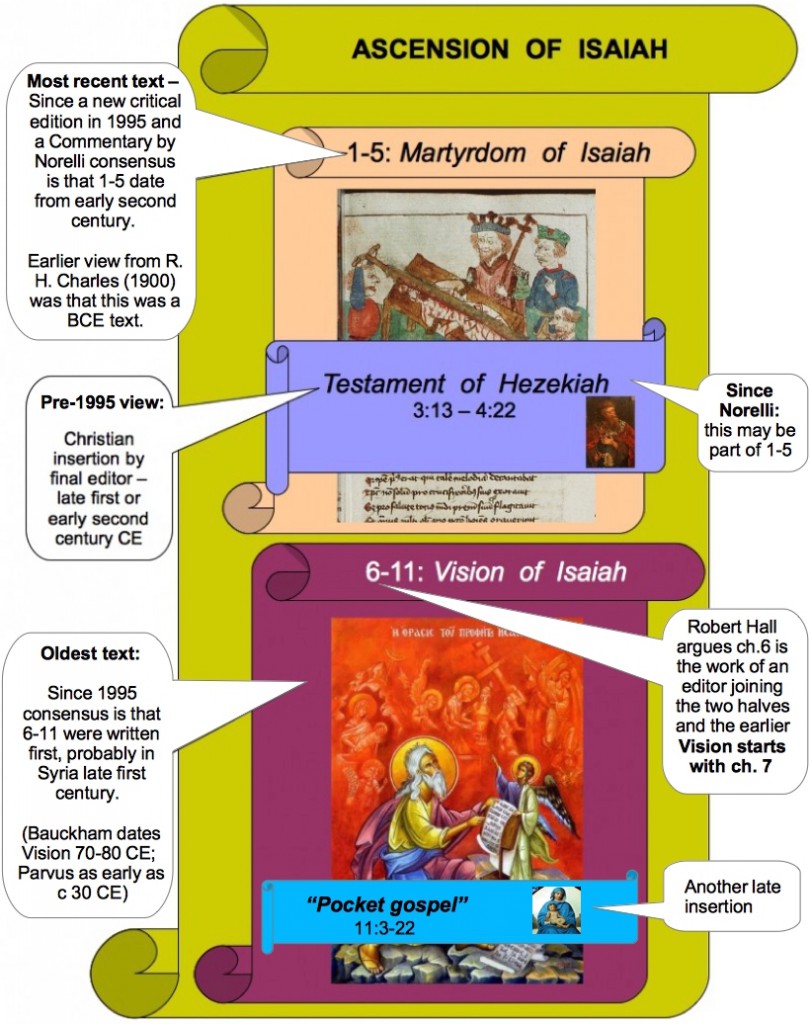

Meanwhile, here is a diagram I prepared for an older post of mine (before I had a copy of Norelli’s book) that shows something of the complexities of the history of interpretations of the Asc. Isa.:

P.S. If anyone capable is interested in translating the chapter let me know in case I am able to forward a copy of the chapter.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Has a date range of composition been proposed or is he just saying contemporaneous with Matthew whenever that was composed?

If Norelli is right, does this undercut a lot of the support Asc. Isa. is supposed to give for Doherty/Carrier-style mythicism? They of course have a lot of evidence other than Asc. Isa. but would Asc. Isa. in any case be taken out of the mix, since it would no longer seem to be a case of an early Christian text showing Christ existing solely celestially?

If you take Asc. Isa. out of the mix, you have no good, tangible evidence that a celestial-Christ-only sect existed. Docetism cannot be roped in, because its logic is not that Christ didn’t come to Earth, but that he wasn’t the human he appeared to be while on Earth.

I wouldn’t say Asc. Isa. itself is tangible evidence that a celestial-Christ-only sect existed. The two extant versions of Chapter 11 are completely different (the terse S/L2 and the verbose E/L1) but they both say in so many words that Christ lived on earth, and they both strongly imply docetism. The terse version states “he dwelt with men in the world”. You are completely right that docetism is not a “celestial-Christ-only sect”.

Note that docetism is compatible with Parvus’ take on the Ascension of Isaiah, since unlike Carrier and Doherty, Parvus argues that Asc. Isa. is docetist originally: it originally described the Christ killed in human form while on a brief visit to earth. Indeed, the terse version of chapter 11 does not contradict Parvus, although he believes there was once a much longer version that is no longer extant.

What I meant is that Asc. Isa. can be construed as tangible evidence for the celestial Christ theory if one accepts the Carrier/Doherty approach to the verses about dwelling on Earth (and, for that matter, the nativity story).

Very interesting. I don’t think that proving Jesus never existed depends on proving that the earliest form of Christ worship espoused a celestial crucifixion, but a celestial crucifixion sure makes the case easier to make.

Still I think Jesus is different from Isaiah in this regard. Because the role of Isaiah was to confront the followers of Beliar, but the role of Jesus was to destroy the material world and create a new immaterial world in heaven.

This means that the task of Isaiah had to be done on earth, where the followers of Beliar were, but the task of Jesus is different. The task of Jesus is to destroy the material world.

Thus, there are reasons that Isaiah would have come to earth that are different than the motives for the actions of Jesus.

My view of the early Jesus is EITHER that the early Jesus could never have been imagines to be material or to have come to earth, because Jesus was to be a superior immaterial messiah who was uncorrupted by the evil material world, OR Jesus had to have come to earth and become material and have his material flesh destroyed mirroring his destruction of the material world.

In other words, as far as the early theology goes I can see how Jesus become material could make sense, if his becoming material, being killed, and then being raised immaterial was supposed to mirror his task of killing the material world and raising a new immaterial world.

But one could also argue that the task of creating a perfect immaterial world could only be taken on by a messiah who had never been corrupted by becoming flesh himself.

Either way, however, we are still dealing with myth, and I don’t think anyone would argue that the Isaiah of the Ascension narrative was a real person. Indeed I would say that the case for Isaiah having ventured to earth via Mary being original further boosts mysticism, because it provides a model for an earthly mythical Jesus.

The problem now is that we’ve somewhat staked the mythicist position on the idea that the first conception of Jesus was that he was totally heavenly and never ventured to earth.

What this interpretation of Asc. Isa. does is provide a model for an earthly mythical savior.

As for the question of dating, I can only say at this stage that Norelli places the Asc. Isa.Asc. Isa.Asc. Isa.vvv distinctly earlier than many of the concepts that we see from early or mid-second century on.

As for the question of mythicism, while the Doherty-Carrier view has become the most well-publicized view it has never been the only (nor always the most “popular”) Christ Myth hypothesis. The argument for it is indeed strong and stands quite apart from the Asc. Isa.. Only those who have never read Doherty or Carrier but only the works of critics who likewise have only skimmed their works and constructed straw-man versions of their theses would think removing the Asc. Isa. undercuts their arguments.

What interests me the most about Norelli’s apparent argument is the nature of the rival Christian group alongside the one that produced the Gospel of Matthew. The argument for mythicism is not undercut by Norelli but Norelli’s understanding of the Asc. Isa. may take the argument in a different direction from what has been considered before. (Of course I do not for a moment suspect Norelli is himself a mythicist.)

I’ll comment further as I take more time to post paraphrases of chapter 2 here.

The Christian sect responsible for the Asc. Isa. (all of it) was exalted revelations through visions and saw themselves competing with rival sects, each blaming and persecuting the other as false prophets.

Interesting. Of course, this would certainly cause the Roman authorities to classify the whole lot as a dangerous and lethal superstition ( exitiablilis superstitio and outlaw it.

The account of the birth of the Beloved to Mary in Bethlehem is not a late addition but was original to the vision chapters (6-11). That means The Beloved did indeed descend to earth and was crucified on earth — unrecognized by the demons.

Well no historical character I know of ever had a magic birth!

Perhaps. My own initial view, for what it’s worth, is that such visionaries were not really different from a number of other Jewish (and non-Jewish) mystical sects,

How can this jive with the Marcan gospel explicitly claiming that the demons did, in fact, recognize Jesus? (Mk 1:23-24, etc.).

Awkwardly. Looks like Mark has transferred the ignorance motif from the demons to the humans.

Fascinating article by George T. Zervos (UNC), referencing Norelli, comparing/contrasting Asc. Isa. to Matthew, and proposing a source (Genesis Marias) common to Asc. Isa. and Protevangelium of James for the Marian material.

Seeking the Source of the Marian Myth:

Have We Found the Missing Link?

Thanks for that link. I may address it when I come to posting the relevant section of Norelli’s summary. Another commentary on the “recent” scholarship on the Asc. Isa. is from Richard Bauckham in The Fate of the Dead: Studies on the Jewish and Christian Apocalypses. From pages 363-365:

And two paragraphs from Richard Bauckham’s review of a collection of essays on the Asc. Isa. by Norelli that were produced as a companion to his larger commentary:

I’ve commented on Norelli’s conclusion that the Asc. Isa. drew upon a tradition also known to Matthew; Bauckham’s second point points to one of the features that early Christianity shared with other mystery religions.

Neil: “Bauckham’s second point points to one of the features that early Christianity shared with other mystery religions.”

and your other comment above: “Perhaps. My own initial view, for what it’s worth, is that such visionaries were not really different from a number of other Jewish (and non-Jewish) mystical sects,”

No doubt. For instance, I’m reminded of Merkabah mysticism and the divine throne theme also found in Asc. Isa., along with singing praises.

Yes, and interestingly, Zervos does bring into discussion ideas of Bauckham, Knight, and Hall.

Hi Neil,

I have a copy of Norelli’s Ascension d’Isaïe and I consulted it when I wrote parts 7 through 9 of my blog series on a Simonian origin for Christianity. In part 7 of the series I noted in passing that Norelli put the date of composition for the Vision of Isaiah at the end of the first century. And in post 8, as part of my Jan. 30, 2014 response to George Hall, I quoted from page 52-53 of Norelli’s book.

However, just judging from this one book of Norelli’s, I’m skeptical that his work will prove to be, as Bauckham says, “definitive.” And I don’t see that Bauckham himself really considers it all that definitive either for, as I recall, Bauckham argues that Norelli is wrong about assigning a different author to each of the two parts of the Asc. Isa. and about Norelli’s dating of the second part (the Vision of Isaiah) earlier than the first (chapters 1-5).

In regard to the Asc. Isa.‘s chapter 11 “pocket gospel:” I explain in post 8 my reasons for questioning whether it was part of the original Vision. As you know, I share Carrier’s and Doherty’s suspicions that it was not, but we have different guesses about what was originally there. I proposed that some kind of early passion narrative like the one now found in gMark would fit in better with the rest of the Vision

I think that Asc. Isa. has marcionite influence and then it’s later middle II CE. The only reason for a mythical heartly Jesus is hate of world as creation of Demiurg. The author of Asc. Isa.I, if I follow Norelli’s reconstruction of original text, is a JudeoChristian from the same sect of Revelation (in Revelation there is a woman and a birth, too) with the intention to identify the Demiurg with Satan and not with the God of Jews (against Marcion).

I read that the Asc. Isa. III 13.18 bears ”angelic Marcionite elements, such as the light metaphors, the angels, and the glory and brightness of the Risen.” However, it also ”shows clear emphasis on realism. It sets great store on the facticity of the Resurrection. It is neither a mystery hidden out of time, nor an inner experience conveyable only to perfect insiders, but a knowable event.”

It would be interesting to know the Roger’s view on this aspect.

What evidence is there that “light metaphors, the angels, and the glory and brightness of the Risen” are angelic elements that are distinctively Marcionite? And even assuming they were, I don’t see any reference to “light” or “glory” or “brightness” in 3: 13-18 of the Asc. Isa.. What translation are you using? There are angels in the passage, but I am not aware that “Michael, the chief of the holy angels” (Asc. Isa. 3:16) was any kind of a favorite with Marcion. Do you know of some particular patristic passage that says Michael had a role in Marcion’s gospel?

To me, the passage looks Jewish Christian, not Marcionite.

excuse me, Roger, I have not explained well my view. I think that all these elements (…“light metaphors, the angels, and the glory and brightness of the Risen”…) show a marcionite influence on a Jewish Christian sect basically hostile to Marcion – and then a sect who writes basically in reaction, but under influence too, against Marcion.

Obviously it’s only a possibility. But if Norelli is right on the presence of birth in Asc. Isa.I (and I don’t know if he is), I can only imagine that Asc. Isa. was written after Marcion and before GMatthew. A birth is necessary for the Son only for who polemizes against Marcion.

A question: in Jewish-Christian Revelation (last I CE) there is a woman, too, and a birth. It’s all allegorical? Or is it an element of original myth of Pillars?

My guess would be that the woman is allegorical. Revelation was written by a prophet who saw himself as belonging to some kind of band of “brother prophets” (Rev. 22:9). The woman is perhaps an allegorical stand-in for that prophetic movement that gave birth to Christianity. Through them the existence and entrance into the world of the “son … who will rule all the nations with an iron rod” (Rev. 12:5) was made known. In that sense they gave birth to him. That birth brings them to the attention of the Dragon and he pursues them.

There is, by the way, some resemblance between this and the Asc. Isa.. There we again have a band of prophets who are distinct from the rest of the believers. And Beliar gets “very angry with Isaiah because of the vision… that through him there had been revealed the coming of the Beloved from the seventh heaven, and his transformation, and his descent, and the form into which he must be transformed, (namely) the form of a man…” (Asc. Isa. 3:13).

Michael, defined in the Book of Daniel, is totally incompatible with Marcion, whose Jesus is explicitly not the messiah of Daniel.

Intriguing stuff this time.

Of course, the point made here: “to save humanity by means of conquering their demonic rulers” shows that the group associated with this part (or all) of Ascension of Isaiah were still working from the same ideas as Gnostics.

There’s also the point that it used material in common with Matthew without quoting or using Matthew.

Here’s a suggestion…might The Ascension of Isaiah have been closer to the Gospel of the Hebrews? And perhaps more so than the Irenaean version of Matthew?

By the way, Neil, have you done any more research on Hegessipus? I remember from last year you were going to be doing a post on that.

I’m still intrigued at the fact there was someone going around in the mid-second century trying to style himself a Christian Josephus and I’m curious as to how much of real Josephus he used. Would we consider such a Pseudo-Josephus a forger? And what sort of impact would he have had on the churches or early fathers of the mid-second century?

Then again, I’m aways wondering why Josephus was chosen by Christians of the earliest centuries to use for reference instead of the other noted historian, Justus, secretary of Agrippa II…though the early chapters of Acts seems to answer that in an oblique way.

No I haven’t, George. Too many other interesting things keep Hegessipus a few points down on my priority list.

I read:

The text insists that Jesus really died, leaving open to question the manner of his earthly appearance but insisting nonetheless that the humanity is real. The Christology is, if anything, more obviously anti-docetic than docetic in terms of what is said about the passion in 3.13, 18 and 11.19-20.

..

In the wake of the present study, it emerges that the authors stand much closer to Ignatius than has been realized.

(from J. Knight, The Christology of the Ascension of Isaiah, in The Open Mind, 2015)

Surprendent idea:

And if the Ascension of Isaiah (like Revelation, too) was only one of first various Judeo-christian attempts of response and reaction against the gnostic first introduction of Messiah’s death?

In such case one possible scenario may be similar to this:

1) 70-90 CE: some Jew preachers/Spirit-possessed predicted the imminent future arrival of Messiah ‘Joshua’ (Didache, Enochic leterature) meaning generic ‘salvation’.

2) 90-110 CE: the first Gnostics among them (Simon Magus? Cerinthus?) invented the idea of a (only apparent) Messiah Jesus dying by hand of ‘Jews’ on earth and ascending up to heaven.

3) 110-120 CE: the same Jews of point 1, instead of rejecting the entire concept of Messiah’s death on earth as basically alien to their beliefs, incorporated it into Jewish sacrificial system (Revelation, Hebrews, Barnabas, Odes of Solomon, Ascension of Isaiah…) and linking that death to fall of Temple.

4) 120-140 CE: The Marcionites attempted to armonize Jews and Gnostics with their fictitious leterature (”Paul”) and their Earliest Gospel.

5) 140-200 CE: But the proto-orthodox Judaizers prevailed after splitting Mcn in our four canonical Gospels.

I believe that, only if you reject a priori as mere apologetical armonization any scholar suggestion about a presumed basically Jewishness of concept of a dying messiah, then the only possible conclusion is that above.

Giuseppe

Maybe after Jesus was killed on a “tree” its curse was removed among his followers by reflection on e.g. Isaiah 53.3 and Daniel 9.26. The gospel “chronology” seems to be fitted into the prophecy in Daniel.

Neil I didn’t read all the comments after your post but above I did notice your moment of humility, questioning your French. But rest assured. You have Norelli’s thesis about right and seem to have understood the book. This view is characteristic of the Italian school—it was not too well known to Jonathan Knight in his 1995-1996 books, but it forms the basis of subsequent scholarship on the Asc. Isa. (unlike Knight, who regularly gets short shrift). Cheers, Matt

So you would say there has long been a general divide between European and “English speaking”(?) scholarship on the Asc. Isa. or is that reading too much into your comment?

P.S. I like the diagram.

Not possible for the original to have included 11:2-22. The demons lay their hands on the beloved in the firmament, so he cannot be an unknown crucified in Jerusalem.

My feeling is that the original Vision included ii cor. 2:9, which Paul quotes as scripture, and that the Pauline citation “and he ascended on the third day, according to the scriptures” (i cor 15) are from the Vision, which was regarded as genuinely Isaiahan by a protochristian group. (“the mystery kept secret for long ages” etc.) The solitary possibility for a scriptural quote mentioning resurrection on the third day otherwise comes from a single verse in Hosea, which is about revival, not resurrection or ascension and uses the first person plural so could not be understood to refer to a solitary person with heavenly origins.

I agree with Roger Parvus that L2 reflects the original, for a close reading of Charles demonstrates its more primitive, less embellished character.

I’ll be posting again on Asc. Isa. soon. Will look at some of these basics through Norelli’s eyes.