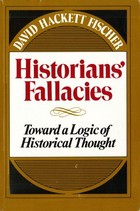

For the ordinary lay person who does not have the background to draw upon to enable a confident “vetting” the arguments of a consensus, I thought the three-part conditions set out by Avazier Tucker were a good rule of thumb for when to justify appeal to a consensus. It certainly provides a good answer to anti-vaxxers. Similarly, it offers good guidance to conspiracy theorists of various types. (Not that many of them would be convinced, of course, but it is nonetheless good to have “an answer” out there for those who are ready to change their minds.)

Richard Carrier thought Tuckers’ three part program was no answer at all to the problems he raised. It’s my fault entirely. I sneakily hid Tucker’s antidotes to the very problems Carrier raised in between the title and the last line of the post so anyone can be excused for missing them.

Carrier wrote,

These conditions cannot be met in captured fields (e.g. you will never ever see a “consensus” in biblical studies by this definition that Jesus did not rise from the dead and is not God or the literal Son of God), so it is not useful as a metric.

Oh dear — my fault entirely. I should not have hidden the fact that Tucker’s three point proposition is explaining exactly why what is regarded as a consensus in biblical studies is not a justifiable or trustworthy consensus. I really do have to stop hiding the main points of my posts beneath their titles.

But more to the point, and by way of demonstrating how biblical studies fails on Tucker’s point 2 — the issues of Thomas Thompson and Thomas Brodie certainly illustrated the failure of Tucker’s points 1 (coercion) and 3 (coercion but also alert to the public about the heterogeneous character of the opposition to the consensus) in the field of biblical studies — more to the point, as I said, I must point to a work by Michael Alter published in the SHERM journal, Dataset Analysis of English Texts Written on the Topic of Jesus’ Resurrection: A Statistical Critique of Minimal Facts Apologetics —

This article’s abstract:

This article collects and examines data relating to the authors of English-language texts written and published during the past 500 years on the subject of Jesus’ resurrection and then compares this data to Gary R. Habermas’ 2005 and 2012 publication on the subject. To date, there has been no such inquiry. This present article identifies 735 texts spanning five centuries (from approximately 1500 to 2020). The data reveals 680 Pro-Resurrection books by 601 authors (204 by ministers, 146 by priests, 249 by people associated with seminaries, 70 by laypersons, and 22 by women). This article also reveals that a remarkably high proportion of the English-language books written about Jesus’ resurrection were by members of the clergy or people linked to seminaries, which means any so-called scholarly consensus on the subject of Jesus’ resurrection is wildly inflated due to a biased sample of authors who have a professional and personal interest in the subject matter. Pro-Resurrection authors outnumber Contra-Resurrection authors by a factor of about twelve-to-one. In contrast, the 55 Contra-Resurrection books, representing 7.48% of the total 735 books, were by 42 authors (28 having no relevant degrees at the time of publication). The 42 contra authors represent only 6.99% of all authors writing on the subject.

The article is available at the link above. The book referred to with the complete study is A Thematic Access-Oriented Bibliography of Jesus’s Resurrection. I don’t know how Michael had the stamina to undertake such a study, but again, it’s good to have things like this done and available.

On the other hand, some questions are more pressing. Even not making a decision is still a decision. When I think of life-or-death decisions that demand a choice, I can’t help but recall the series

On the other hand, some questions are more pressing. Even not making a decision is still a decision. When I think of life-or-death decisions that demand a choice, I can’t help but recall the series