I’ve been re-reading Propp’s work on the structure of folk tales (Morphology of the Folktale) and this passage struck me this time:

[I]f all fairy tales are so similar in form, does this not mean that they all originate from a single source? The morphologist does not have the right to answer this question. At this point he hands over his conclusions to a historian or should himself become a historian. Our answer, although in the form of a supposition, is that this appears to be so. However, the question of sources should not be posed merely in a narrowly geographic sense. “A single source” does not positively signify, as some assume, that all tales came, for example, from India, and that they spread from there throughout the entire world, assuming various forms in the process of their migration.

Propp, V. (2010-06-03). Morphology of the Folk Tale (Kindle Locations 2049-2053). University of Texas Press. Kindle Edition.

Propp then goes on to raise our awareness of other possible common sources:

The single source may also be a psychological one.

Family life is one such possible single source. Daily living another.

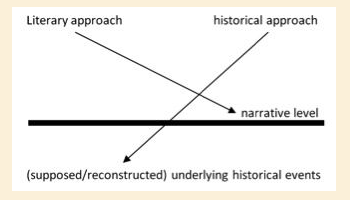

This passage jumped out at me probably because not long before I was re-reading parts of Childs’ book The Myth of the Historical Jesus, in particular his criticism of the assumptions of scholars who study the historical Jesus. He uses Crossan as a typical example:

[I]n a 1998 article, Crossan seems intent on finding and locating a kind of “cause,” or at least the source, for multiform manifest versions of Jesus’ sayings in the original voice of Jesus. He proposes the “criterion of adequacy” to replace the criterion of dissimilarity as the first principle in historical Jesus research. He defines it thus: “that is original which best explains the multiplicity engendered in the tradition. What original datum from the historical Jesus must we envisage to explain adequately the full spectrum of primitive Christian response. (p. 50)

Childs later suggests:

Crossan . . . seems to verge on what is a kind of concretistic historical fallacy in assuming that “the full spectrum of primitive Christian response” can only have its origin in, and therefore must be traced to, the original words and deeds of Jesus. Continue reading “From a single source? Disguising hermeneutics as history?”