Last month I posted Another Pointer Towards a Late Date for the Gospel of Mark? but this morning I was reminded of an article I read and posted about some years back that surely calls for a date soon after 70 CE. That article does not address the date per se but it does raise difficulties for a date very much later than the days of Vespasian’s reign: 69-79.

The article is Spit in Your Eye: The Blind Man of Bethsaida and the Blind Man of Alexandria by Eric Eve (if a nearby library subscribes to Proquest you might be able to access it at no cost there) and my derivative post is Jesus out-spitting the emperor. I won’t repeat the details I set out there except where they overlap with a few points I will highlight here. (See that earlier post for the extracts from Suetonius and Tacitus describing Vespasian’s healing miracles.)

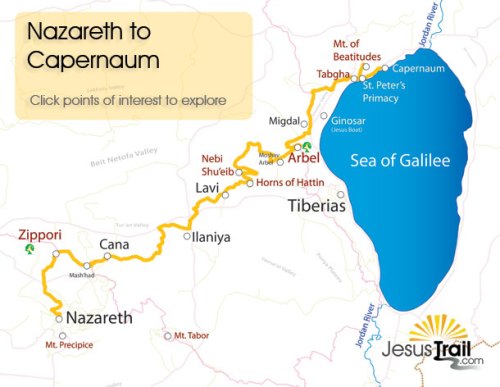

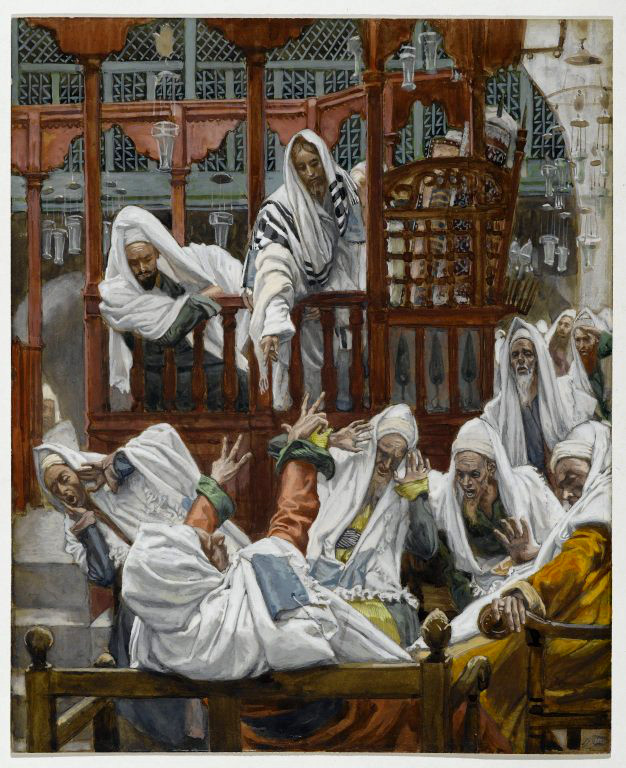

In short, the core of Eric Eve’s thesis is that the author of the Gospel of Mark was responding to Vespasian propaganda that promoted him as a healer and as such either possessed by or strongly favoured by the god Serapis to be the rightful ruler of the world. Vespasian, you might recall (the details are in the earlier post), is known to have “miraculously” healed a blind man through the use of spittle while he was in Egypt and preparing to return to Rome to claim the emperorship.

Since Vespasian was not from the Roman aristocracy he relied heavily on propaganda programs to justify his aspirations to replace Nero and subsequent short-lived rulers. Roman historians, especially Tacitus, inform us that

while Vespasian was waiting at Alexandria. . . many marvels occurred to mark the favour of heaven and a certain partiality of the gods toward him (Hist. IV. 81)

The god Serapis was a composite deity constructed some generations earlier by Egypt’s post-Alexander Hellenistic rulers to encourage the unification of different peoples: (you will note the similarity with other posts suggesting the reason for the creation of Jesus was likewise to encourage a certain unity of Jews and gentiles in another context …. but we leave that for another discussion)

The Egyptian cult involved the worship of the sacred bull Osiris-Apis, or Osarapis, which became Sarapis in Greek translation. It may have been this god’s connections with the underworld and agricultural fertility that made him appear particularly suitable for the grafting on of Hellenistic elements. Sarapis took on the attributes of a number of Greek deities including first Dionysus and Hades, and subsequently Zeus, Helios and Asclepius [my note: Asclepius was the god of healing]. He may originally have been intended as a patron deity for the Greek citizens of Ptolemaic Alexandria, but he became particularly associated with the royal family, and thus, perhaps, with a ruler cult. Although Sarapis was probably intended to unite the Greek and Egyptian populations (of Alexandria, if not of Egypt), he failed in this purpose, since he never caught on with the native Egyptian population. He proved more popular with the Greek inhabitants, although his popularity declined towards the end of the Ptolemaic period. By the Roman period, Sarapis’s popularity seems to have been on the rise once more, and his cult had long since spread well beyond Egypt, aided, no doubt, by the fact that he was the consort of Isis; both deities had cults in Rome by the time of the late republic. That said, the major rise of the cult of Serapis was to come about through Flavian interest in the god. Vespasian arrived in Alexandria at a time when association with an aspiring emperor could benefit an aspiring god as much as the other way round; the Sarapis cult’s support for Vespasian helped both parties, and that may well have motivated the priests of Sarapis to play their part in the Flavian propaganda campaign.

The healings carried out by Vespasian seem designed to demonstrate the close association between the new emperor and the god. Healing was one of the powers long attributed to Sarapis, and the first healing miracle to be attributed to him was restoring sight to a blind man, one Demetrius of Phaleron, an Athenian politician. . . . In some minds Vespasian’s two healings might be taken as a sign, not simply that Vespasian enjoyed Sarapis’s blessing, but that he was in some sense to be identified with the god. This is in part suggested by the ancient Egyptian myth that the kings of Egypt were sons of Re, the sun-god, and is further borne out by the fact that Vespasian was saluted as ‘son of Ammon’ as well as ‘Caesar, god’ when he visited the hippodrome only a short while later.

Presumably the main targets of this propaganda were the population of Alexandria and the two legions stationed there, whose support Vespasian clearly needed to retain. No doubt different people will have understood this cluster of events in different ways. Some may have seen Vespasian as quasi-divine, others as a divinely aided thaumaturge and others as an exceptionally lucky man smiled on by fortuna and the gods. In any case the healing miracles and their association with Sarapis seem to have been designed more for eastern than western consumption.

The classicist and specialist in Suetonius, David Wardle, is more direct with the reason for Vespasian’s miracles: Continue reading “Spit at a Late Date for the Gospel of Mark?”