Creative Commons Attribution

That the gospels recycled themes, motifs, sayings, can be found across the Middle East from Mesopotamia to Egypt and stretching back millennia to before the Neo Babylonian empire and even before the time of any Jewish Scriptures will be of no surprise to anyone who has read The Messiah Myth by Thomas L. Thompson.

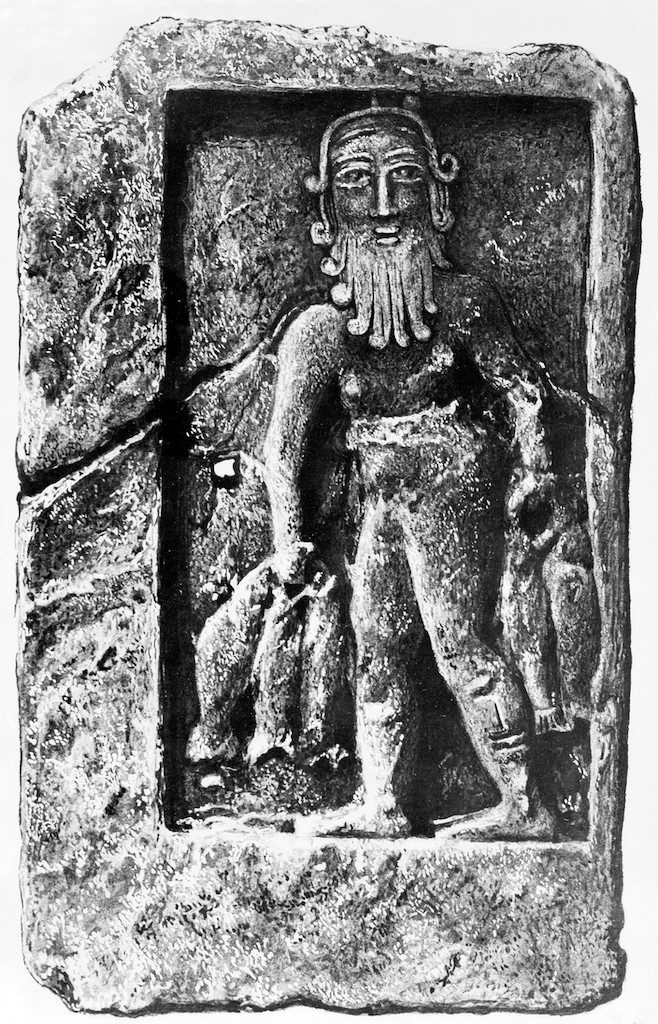

Of the myth of Adapa and the South Wind “the earliest known version is a Sumerian text from Old Babylonian Tell Haddad”, made available by Cavigneaux in 2014. I have part translated, part paraphrased the opening section of Cavigneaux’s French translation of the often broken Sumerian text, and added a distinctive note on one comment that I found particularly interesting.

In those distant days …

After the Flood had swept over,

and brought about the destruction of the land …

The world is reborn

A seed of humanity had been preserved …

Four legged animals once again widely dispersed …

Fish and birds repopulated the ponds and reedbeds …

Herbs and aromatic plants flowered on the high steppe …

The state is born

An and Enlil organized the world …

The city of Kish became a pillar of the country …

Etana becomes king

Then the elected shepherd …

Founded a house …

The South Wind during his reign brought blessings …

Humanity without a guide

Humanity did not have a directive …

[Nobody knew how to give or follow orders]

The Story of Adapa begins

[A loyal devotee of Enki he goes fishing in the quay to supply his master’s temple in Eridu.]

In later exorcistic texts … the quay (Akk. kārum) is a trope for the liminal space between worlds.

At the New Moon he went up to go fishing

Without rudder he let the boat go with the flow

Without pole he went up the stream

On the vast lagoon …

[He is capsized by the South Wind]

He curses the South Wind …

And broke the wings of the South Wind …

The narrative is thus a reference to the destruction of the old world and the restoration of the new, through a Flood or through water bringing about the end of one world and nourishing the emergence of the new. As Thompson observes in The Mythic Past new worlds emerge through parting waters (Creation, Noah, Exodus, Elijah-Elisha, Jesus’ Baptism/heavens divided).

Adapa has a special gift. Though mortal, he has power over words, or rather his words have power over the world. Adapa will become the great mythical sage of scribes, of all who can with the magic of words change the face of the earth and the organization of society: engineers, architects, legislators, ….

We are familiar with astronomy and astrology being all one branch of knowledge in these times; similarly magic and medicine were indistinguishable at this stage. The skills of the scribes, the amazing feats they accomplished with words, appear to have been supernatural gifts.

After Adapa by merely speaking causes the wind to cease the supreme god is astonished and invites him up to heaven. Adapa’s personal god, however, warns Adapa not to accept certain gifts [bread, drink, a coat] that will be offered to him there but to only accept an anointing. The chief god laughingly tells Adapa that he has just refused the gifts that would have given him eternal life.

And so forth.

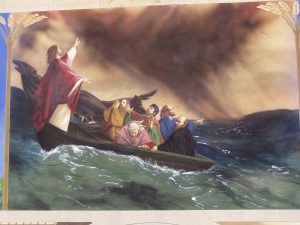

We see here a story opening with the water, a flood, separating the old and the new. We see the wise hero wielding power over the elements, even stilling a “storm”, by his mere commands. Others are amazed at his ability. In this case, it is the gods who are amazed.

The plot of the story begins with the sage “going fishing”, a scene that is found to have mythical or metaphorical significance of life and death, entering a space between two worlds.

I find such literary comparisons interesting. I’m not saying the evangelists were adapting the myth of Adapa, of course. I am thinking about the way certain mythical tropes have been recycled and refashioned through changing human circumstances and experiences.

Cavigneaux, Antoine. 2014. “Une Version Sumérienne de La Légende d’Adapa (Textes de Tell Haddad X).” Zeitschrift Für Assyriologie Und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 104 (1): 1–41. https://www.academia.edu/26276183/Une_version_sum%C3%A9rienne_de_la_l%C3%A9gende_d_Adapa_Textes_de_Tell_Haddad_X_

Sanders, Seth L. 2017. From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. 42