Christianity and slavery: why does it matter?

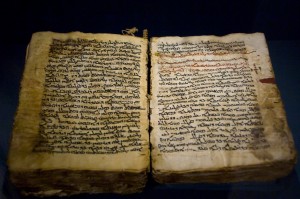

As I made clear early on in this series, I contend that the institution of slavery in the Greco-Roman world was more terrible than we can imagine. In addition, we can’t deny the evidence that early Christians were generally ambivalent about it, or at worst, condoned it. Moreover, rich Christians continued to own slaves after they converted. We can, in fact, corroborate these assertions not only from ancient writings, but from certain artifacts that still survive.

Investigation of current Christian attitudes toward ancient slavery reveals a surprising number of people who prefer to remain in a state of denial. Recall from part one Thomas Madden’s unsubstantiated assertion that “Christianity . . . considered slavery — the institution of slavery — to be inherently wrong.” Not only can we find no clear written evidence from the New Testament or patristic literature to confirm his claim, but we have solid written and archaeological evidence that disproves it.

The crime of running away

Jennifer Glancy begins her book, Slavery in Christianity, with the following few sentences that, for Christians (and ex-Christians like myself) are as sobering as an ice-cold shower:

Sometime in the fourth or fifth century, a Christian man ordered a bronze collar to encircle the neck of one of his slaves. The inscription on the collar reads: “I am the slave of the archdeacon Felix. Hold me so that I do not flee.” Although the collar purports to speak in the first person for a nameless slave, the voice we hear is not that of the slave but that of the slaveholder. Felix, enraged by a slave’s previous attempts to escape, ordered the collar both to humiliate and to restrain another human being, whom the law classified as his property. The chance survival of this artifact of the early church recalls the overwhelming element of compulsion that operated within the system of slavery, with its use of brute paraphernalia for corporal control. (p. 9, emphasis mine)

The words “chance survival” might lead the reader to think such collars — which gave license to the finder to detain the slave by any brutal means necessary, and which were lovingly adorned with crosses and chi-rhos — were rare. But they weren’t. True to form, some scholars have decided to interpret the existence of such collars as a good thing. They posit that it means Christian slaveholders stopped the practice of facial tattooing. In other words, “Baby steps.”

However, in the (ridiculously overpriced) book, Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275-425, Kyle Harper notes:

Continue reading ““With All Fear”: Christianity and Slavery (Part 4)”