A number of readers have questioned my own questioning of a popular belief and claim by Richard Carrier that

Palestine in the early first century CE was experiencing a rash of messianism.

I suggest on the contrary that evidence for popular messianism does not appear until the Jewish War in the latter half of the first century. See post + comment + comment and links within those comments to earlier posts. Certainly popular counter-cultural leaders prior to that time (but still well after the time of Jesus) did not imitate any known Danielic or Davidic notion of a messiah expected to challenge Rome.

In this post I will address some general background information that we have about popular messianic movements. If we are to be good Bayesian thinkers then we need to set out as much background knowledge as we can before we begin. This post will put two or three items on the table for starters. Other background data has been covered to some extent in the above linked “comment(s)” and “post”.

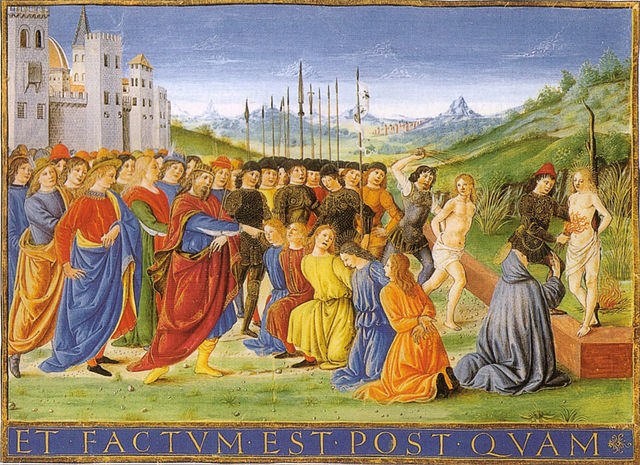

Medieval Messianism

A classic study of popular millennial movements is Norman Cohn’s The Pursuit of the Millennium . After surveying such movements in the Middle Ages Cohn concludes:

A classic study of popular millennial movements is Norman Cohn’s The Pursuit of the Millennium . After surveying such movements in the Middle Ages Cohn concludes:

“They occurred in a world where peasant revolts and urban insurrections were very common and moreover were often successful. . . .

“Revolutionary millenarianism drew its strength from a population living on the margin of society – peasants without land or with too little land even for subsistence; journeymen and unskilled workers living under the continuous threat of unemployment; beggars and vagabonds – in fact from the amorphous mass of people who were not simply poor but who could find no assured and recognized place in society at all. These people lacked the material and emotional support afforded by traditional social groups; their kinship-groups had disintegrated and they were not effectively organized in village communities or in guilds; for them there existed no regular, institutionalized methods of voicing their grievances or pressing their claims. Instead they waited for a propheta to bind them together in a group of their own.

“Because these people found themselves in such an exposed and defenceless position they were liable to react very sharply to any disruption of the normal, familiar, pattern of life. Again and again one finds that a particular outbreak of revolutionary millenarianism took place against a background of disaster . . . ”Excerpt From: Cohn, Norman. “The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages.” iBooks. (My own bolded highlighting)

Examples of those camel back-breaking disasters and related messianic movements:

- Plague –> the First Crusade and the flagellant movements of 1260, 1348-9, 1391 and 1400;

- Famines –> First and Second Crusades and the popular crusading movements of 1309-20, the flagellant movement of 1296, the movements around Eon and the pseudo-Baldwin;

- Spectacular rise in prices –> the revolution at Münster.

- Black Death –> The greatest wave of millenarian excitement, one which swept through the whole of society . . . and here again it was in the lower social strata that the excitement lasted longest and that it expressed itself in violence and massacre.

Islamic Messianism

Continue reading “Historical Conditions for Popular Messianism — Christian, Muslim and Palestinian”