Larry Hurtado’s ongoing attempts to defend the reasons biblical scholars opt to ignore the arguments of the Christ Myth theory reinforce fundamental points in my original post, Reply to Larry Hurtado: “Why the “Mythical Jesus” Claim Has No Traction with Scholars”. Hurtado’s latest response is Focus, Focus, Focus. Some excerpts and my comments:

The question is whether the Gospels are best accounted for as literary productions that incorporate a body of prior traditions about Jesus of Nazareth, and on that question scholars over 250 years have broadly agreed that they do. The earmarks of the traditions are there all over their texts. The Gospel writers weren’t inventing a human figure, but composing biographical narratives of a figure who had been central from the beginning of the Jesus-movement. The Gospels mark a development in the literary history of the first-century Jesus movement, appropriating the emergent biographical genre. But they were essentially placing Jesus-tradition in this literary form.

That the gospels are “biographies” is not a fact but an interpretation, based most often on Richard Burridge’s What Are the Gospels? A number of scholars have found reasons to be critical of Burridge’s arguments, however, as have I. Both Tim and I have discussed Burridge’s book and some of the scholarly criticisms several times now as well as having written more studies on gospel genre generally, introducing a range of scholarly inputs on that question. But let’s stay focused. A “biographical” genre by itself does not mean that the person written about was historical. The ancient times saw a number of “biographies” written about persons we know to have been fictitious, even though the tone and style indicate to a less informed reader that they are about a “true” person. I have discussed several of these in the links above.

Scholars who pay attention to literary studies of the ancient world also know that ancient writers were trained to create details of verisimilitude to make their compositions (letters, novellas, speeches, poems) sound authentic or plausible.

Further, the claim that the gospels “incorporate a body of prior traditions about Jesus of Nazareth” is, in fact, an assumption that is generally “supported” by appeals to details in the text of the gospels that too often are in fact circular. The process is very often an exercise in the fallacy of confirmation bias. The assumption that oral tradition is behind the gospel narratives is the eyepiece through which the gospels are read, and lo and behold, the evidence expected is indeed found to be there. The method has too rarely been checked by controls. A few scholars have applied controls to these arguments, however, and have found that in several cases the evidence that was claimed to be support for oral tradition is, in fact, more directly found to be a sign of literary borrowing. Take, for example, the “rule of three”. Words, motifs, incidents in folktales are often repeated three times and this is said to be an aid to memory. Fine. But what is overlooked is that we find the “rule of three” also liberally populating very literary works with other literary influences.

Yes, I am very aware of studies on oral traditions in the Balkans and Africa and have addressed several of these in posts on this blog. Unfortunately, I have also found that in too many cases a scholar has quote-mined such a study and misapplied its statements to support an otherwise gratuitous claim about gospel origins.

The applicability of those oral tradition studies have been found by a number of scholars not to be applicable to the data we find in our canonical gospels. Again, see some of the posts on Vridar for references to some of the scholarly works addressing this question. I will be posting more in future.

Hurtado continues:

Another reader seems greatly exercised over how much of the Jesus-tradition Paul recounts in his letters, and how much Paul may have known. Scholars have probed these questions, too, for a loooong time. E.g., David L. Dungan, The Sayings of Jesus in the Churches of Paul (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971). But, in any case, this isn’t the issue of my posting, or even essential to the “mythical Jesus” question.

Yes, and indeed it is “many scholars” who also write in their publications of Paul’s virtually complete lack of interest or even knowledge of the human Jesus. Unfortunately, Hurtado appears to have chosen not to even consider or read any of the criticisms of those arguments that bypass certain critical problems with those common assumptions about Paul’s supposed references to the “historical Jesus”. Again, the works available, by both mainstream scholars and Christ Myth theorists, are abundant and discussed in past posts.

The Pauline question is whether his letters treat Jesus as a real historical figure, indeed a near contemporary, and the answer is actually rather clear, as indicated in my posting. Paul ascribes to Jesus a human birth, a ministry among fellow Jews, an execution specifically by Roman crucifixion, named/known siblings, and other named individuals who were Jesus’ original companions (e.g., Kephas/Peter, John Zebedee). Indeed, in Paul’s view, it was essential that Jesus is a real human, for the resurrected Jesus is Paul’s model and proto-type of the final redemption that Paul believes God will bestow on all who align themselves with Jesus. In Paul’s view, what God did to/for Jesus is what God will do for Paul and others who respond to the gospel.

Here Hurtado is glossing over a number of peer-reviewed scholarly studies that contradict some of his points. That conservative scholars choose to ignore these studies does not change the fact that they exist and stand as challenges to the claims by Hurtado here. See, for example, posts discussing the scholarly debate over a passage in 1 Thessalonians that speaks of Jews in Judea being responsible for Jesus’ death, discussions on the passage in Galatians that speaks of Jesus being “born of a woman”, and even my most recent summary of some (only some) of the points relating to the question of James being a “brother of the Lord”.

Hurtado’s assertions are not facts; they are interpretations that are indeed debated in the scholarly literature. Yes, conservative scholarship might dominate the guild today, and minority views might be ignored. But they do exist and ought to be considered fairly.

Of course, with the Jesus movement of his time more widely, Paul also ascribed to Jesus a post-resurrection heavenly status and regal role as God’s plenipotentiary, and likewise (and on the basis of Jesus’ heavenly exaltation) a “pre-existence”. But for Paul and earliest believers it wasn’t a “zero-sum game,” in which Jesus could only be either a human/historical figure or a heavenly king. For them, the one didn’t cancel out the other.

Hurtado here conflates “human” with “historical”. I suggest the equation is not necessarily valid given that the world has seen perhaps as many fictitious humans in its cultural history as non-human ones. Some Christ Myth theorists propose that Jesus was always entirely non-human. My own interests are in a different area, but as far as I understand, it makes no difference to the historicity question if Jesus was thought to appear as a human for a few hours, days, or even years, or even having “slipped through” the womb of Mary in order to be “human”. Let’s stay focused.

The earliest circles of the Jesus movement ransacked their scriptures to try to understand the events of Jesus, especially his execution and (in their conviction) his resurrection. But it was these historical events that drove the process.

Again, this is mere assertion, an assumption, for which there is no independent evidence. The justifications for the claim derive from circular reasoning, I suggest. Or at least they are simply begging the question of the existence of Jesus. The evidence that is before us allows for quite another interpretation: that the early Christians derived their knowledge of Jesus from revelation, including the revelation of scriptures. Again, such viewpoints have been discussed at length many times on this blog.

Finally, this discussion is about history, not theology or faith. What you make of early Christian claims about Jesus’ significance, how you view traditional Christian faith, etc., are all quite separate matters from the historical judgement that Jesus of Nazareth was a real early first-century Jew from Galilee.

Oh that that were true! The Christian faith, it must be kept in mind, is faith that a certain event in the past was more than just theological; it was historical. Faith in the historicity of the event is what Christianity is all about for most conservative Christians.

A handful of Christians I know of have found a way to move beyond such an earthly bound faith (as Schweitzer himself believers them to do) and have found a way to remain Christian even without belief in a historical Jesus. (Not that Schweitzer did not believe in a historical Jesus; he did. But that was not his spiritual message. See Schweitzer in context)

So, let’s stay focused, folks.

Indeed. Focused, but not blinkered.

Like this:

Like Loading...

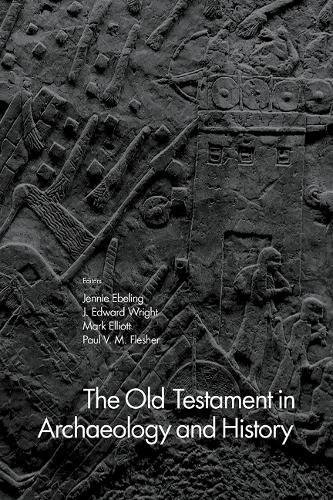

These posts for most part are following the argument of Wright, Elliott and Flesher in “Israel In and Out of Egypt”, a chapter in The Old Testament in Archaeology and History (2017), edited by Jennie Ebelilng, J. Edward Wright, Mark Elliott and Paul V.M. Flesher.

These posts for most part are following the argument of Wright, Elliott and Flesher in “Israel In and Out of Egypt”, a chapter in The Old Testament in Archaeology and History (2017), edited by Jennie Ebelilng, J. Edward Wright, Mark Elliott and Paul V.M. Flesher.