Continuing my posts on Shelly Matthews’ 2017 article. . . .

I am one of those who have leaned favourably towards arguments that our canonical form of the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts were early to mid second century attempts to take on Marcionism. See my series on Joseph B. Tyson’s Marcion and Luke-Acts: A Defining Struggle for instance. Others who have raised similar arguments in recent years are Matthias Klinghardt and Markus Vincent; further, Jason BeDuhn and Dieter T. Roth have produced new reconstructions of Marcion’s gospel.

If Marcionites believed in a Jesus who was not literally flesh and blood like us but only appeared to be so, then it has been argued that Luke (I’ll use that as the name of the author of the Gospel of Luke in its final canonical form) introduced details of how Jesus was very much a fleshly body when he was resurrected and showing himself to his followers. See the previous post for the details.

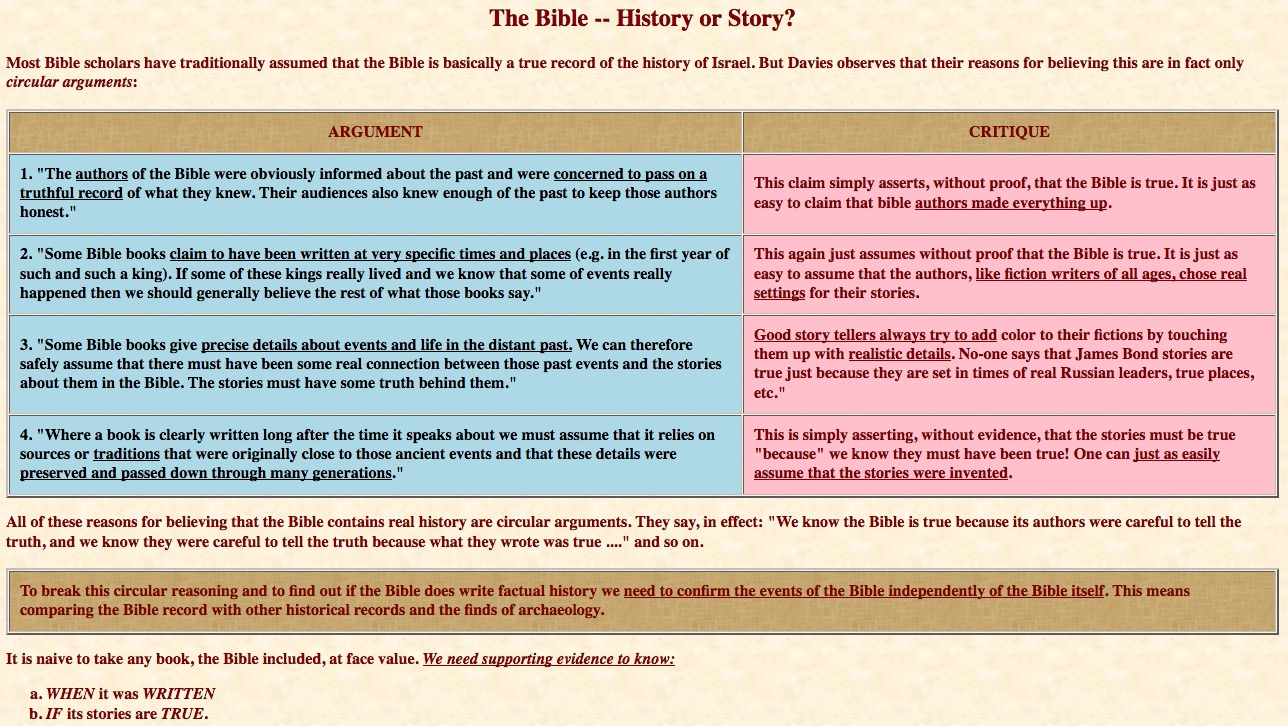

Resurrection accounts overlap

Matthews draws attention to a problem with this view. The “problem” is that all reconstructions of Marcion’s gospel (even BeDuhn’s and Roth’s) include at least significant sections of Luke’s fleshly portrayal of the resurrected Jesus. Jesus says in Luke 24:39 and in Marcion’s gospel according to all reconstructions:

Look at my hands and my feet. . . . . a ghost does not have . . . bones, as you see I have.

Marcion’s Jesus also eats just as Luke’s Jesus does in the same chapter. BeDuhn gives Marcion the following and Roth suggests it is at least close to Marcion’s text.

41 And while they still did not believe [were distressed] . . . , he asked them, “Do you have anything here to eat?” 42 They gave him a piece of broiled fish, 43 and he took it and ate it in their presence. . . .

So Marcion’s Jesus, it seems, also had bones and was able to eat fish. Given that that was what Marcion read in his own gospel how can we interpret Luke’s details as an attempt to refute Marcionism, Matthew’s asks. (Not that this “problem” has not been noticed by scholars like Tyson but Matthews is proposing a different way of looking at the data.)

Neither Luke’s Nor Marcion’s Jesus Truly Suffers

Luke’s Jesus may bear a body of flesh, even after the resurrection, but this flesh is not the ordinary flesh of humankind, which agonizes when threatened, writhes when tortured, and decays in death. (p. 180)

Matthews sets aside as an interpolation Luke 22:43-44 that so graphically pictures Jesus in agony sweating great drops of blood in Gethsemane. Shelly Matthews explains:

For persuasive arguments that Luke 22:43-44 is a secondary insertion motivated by concern that Jesus be depicted as suffering anguish in Gethsemane, see Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament, rev. and enl. ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 220-27.

Another difficulty that Matthews’ sees for the view that our Gospel of Luke was finalized as a rebuttal to Marcionism is its portrayal of Jesus “suffering”. I use scare-quotes because Luke’s Jesus does not appear to suffer at all and so looks very much the sort of figure we would expect to see in Marcion’s gospel. In Luke there is no hint that Jesus on his way to the cross or hanging from the cross is in any sort of torment or agony. Luke’s Jesus is totally impassive.

Indeed, on the question of whether Jesus experienced torment either in Gethsemane or on Golgotha, Luke’s passion narrative can be read as an argument for an answer in the negative, as the later interpolator who felt the need to add the pericope of Jesus sweating drops of blood in Gethsemane surely sensed. (p. 180)

Matthews continues:

The Lukan Jesus does employ the verb πάσχω both in predicting his fate (9:22,17:25,22:15) and in reflecting on that suffering as a component of prophecy fulfillment (24:26,46; cf. Acts 1:3, 3:18,17:3).44 Yet, as is well known, narratives of Jesus’s comportment both on the way to Golgotha and on the cross itself suggests that his “suffering” does not include human experiences of physical agony or emotional distress.45

44 As Joel B. Green notes, the phrase “to suffer” in Luke is used to evoke the totality of the passion (The Gospel of Luke, NICNT [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997], 856).

45 Jerome H. Neyrey, “The Absence of Jesus’ Emotions: The Lucan Redaction of Lk 22:39- 46,” Bib 61 (1980): 153-71; John S. Kloppenborg, “Exitus clari viri: The Death of Jesus in Luke,” TJT 8 (1992): 106-20.

(I located each of Matthews’ references [Green and Neyrey] intending to add more detailed explanation from them but not wanting to take unplanned hours to finish this post have decided to leave those details for another day.)

For Luke, then, Jesus’ flesh is not like our flesh. It is not the sort of body that naturally recoils in anguish at pain or even threats of pain. It does not even decay when it dies.

Acts 2:31 Seeing what was to come, he spoke of the resurrection of the Messiah, that he was not abandoned to the realm of the dead, nor did his body see decay.

Acts 13:37 But the one whom God raised from the dead did not see decay.

The idea that flesh of certain persons could in fact be immortal was part of common Greek cultural belief. Matthews cites Greek Resurrection Beliefs for those who are unaware of this fact. (Perhaps that’s another topic I can post about one day. I have touched on it a number of times incidentally with particular reference to Gregory Riley’s Resurrection Reconsidered, as for instance in this post.)

In this post I have addressed some of the areas that would appear to make the Gospel of Luke in close agreement with Marcion’s gospel rather than a direct rebuttal of it.

Furthermore there are other features of Luke-Acts that appear to be directed at extant ideas or disputes that had nothing at all to do with Marcionism as far as we know. Those are for the next post.

Matthews, S. (2017). Fleshly Resurrection, Authority Claims, and the Scriptural Practices of Lukan Christianity. Journal of Biblical Literature, 136(1), 163–183.

Like this:

Like Loading...