On another forum lately there has appeared the question of why there are so many Marys in the gospels and why Jesus’ mother is given that name. With the partial exception of Jesus’ mother, they have no significant plot function at all. They appear then disappear with no obvious narrative role. What’s going on? These questions have arisen coincidentally at a time when I have returned to exploring the gospels as midrash, that is, as writings similar to the Jewish technique of creating new stories by rearranging passages from here and there in their Scriptures. So with the above questions in mind — why is Jesus’ mother named Mary and why so many Marys in the gospels — consider some of the early Jewish beliefs about Miriam, the sister of Moses and Aaron. The stories as we know them all post-date the gospels.

This post is part one.

Prophet and leader of Israel

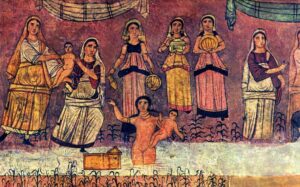

Then Miriam the prophet, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women followed her, with timbrels and dancing. – Exodus 15:20

Miriam and Aaron began to speak . . . “Has the Lord spoken only through Moses?” they asked. “Hasn’t he also spoken through us?” – Numbers 12:1-2

I sent Moses to lead you, also Aaron and Miriam. – Micah 6:4

As a prophet, Miriam was said to have predicted that the saviour of the people of Israel would be born to Amram and Jochebed, her parents.

When Pharaoh issued his decree to slay all newborn male children of the Hebrews, Amram, said to be a leading figure among the Israelites, announced that it would be better to divorce his wife to ensure Pharaoh’s will could not be carried out. The rest of the Israelite men followed his example and divorced their wives. Miriam, his daughter, was outraged against her father and sharply chastised him for neglecting his higher duty to God and the future of Israel: a saviour to deliver them had yet to be born, after all. More specifically, Miriam prophesied that her mother would give birth to a saviour who would rescue them all from Egypt.

Amram was humbled and remarried his wife. Meanwhile, God had restored Jochebed to her youthful state so she was, in effect, a virgin when she remarried her husband.

And a man went from the house of Levi” (Exod. 2:1). Where did he go? Rabbi Yehudah son of Zevinah said: He followed the advice of his daughter. A tannaitic source states: Amram was the greatest man of his generation. When evil Pharaoh decreed: “Every son that is born shall be thrown into the river” (Exod. 1:22), he said: We are toiling in vain. He got up and divorced his wife. They all got up and divorced their wives. His daughter said to him: Father, your decree is harsher than Pharaoh’s, for Pharaoh decreed only concerning the males, and you have decreed concerning the males and the females; Pharaoh decreed only in this world, and you, in this world and for the world to come; evil Pharaoh—perhaps his decree shall be fulfilled, perhaps it shall not be fulfilled, but you are righteous—certainly your decree shall be fulfilled. . . . He got up and brought back his wife. They all got up and brought back their wives. . . . (Sotah 12b)

. . . . —is it possible that she [Jochebed] was a hundred thirty years old and it calls her a daughter [young girl]? . . . Rabbi Yehudah said: Because signs of youth were generated in her. (Sotah 12a)

Then when Moses was born, Amram kissed his daughter in gratitude that her prophecy had been fulfilled. But when Moses was placed in the river Amram lost heart and slapped her on the head for prophesying falsely.

And Miriam the prophetess, the sister of Aaron, took.. . .” (Exod. 15:20). The sister of Aaron, and not the sister of Moses? . . . : This teaches us that she used to prophesy when she was the sister of Aaron and say: In the future my mother will give birth to a son who will redeem Israel. And when Moses was born the entire house was filled with light. Her father stood and kissed her on the head. He said: My daughter, your prophecy has been fulfilled. And when they threw him into the river, her father stood and slapped her on the head. He said to her: My daughter, where is your prophecy? And thus it is written: “And his sister stood from afar in order to know what would be done to him” (Exod. 2:4)—to know what would come of her prophecy. (Sotah 12b-13a)

Yet Miriam did not lose faith and “stood afar off” watching over Moses to ensure his safety. We know how it ended. Miriam managed to retrieve Moses from the Egyptian princess so that his own mother could nurse him.

Miriam is, therefore, the one who prophesied the birth of the saviour of Israel, the one who forbade her father to divorce his wife (or at least to remarry her), the one who protected Moses and ensured his entry into the world. (Similarities and overlaps with any other Christian narrative are surely entirely coincidental.)

God rewarded Miriam for her courage and faithfulness: she was to become the ancestress of the kingship of Israel.

Ancestor of David

In the Talmud (Sotah 11b) it is explained that the names used in I Chronicles (2:18) for Caleb’s wives Azubah and Ephrath are one or the other a pseudonym for Miriam. — Moshe Reiss, p. 190 n.13

Caleb son of Hezron had children by his wife Azubah (and by Jerioth). These were her sons: Jesher, Shobab and Ardon. When Azubah died, Caleb married Ephrath, who bore him Hur. Hur was the father of Uri, and Uri the father of Bezalel. — 1 Chronicles 2:18-20

To return to that Sotah 11b passage cited by Moshe Reiss, here is the relevant section:

David, who also comes from Miriam, as it is written: “And Azubah,” the wife of Caleb, “died, and Caleb took to him Ephrath, who bore him Hur” (I Chronicles 2:19) and, as will be explained further, Ephrath is Miriam. And it is written: “David was the son of that Ephrathite of Bethlehem in Judah” (I Samuel 17:12). Therefore, he was a descendant of Miriam.

The midrashic explanation goes back to the opening chapters of Exodus and the story of the two midwives who delivered the Israelite babies. Pharaoh, again we know the story, ordered the midwives to kill every newborn male but the midwives responded by pleading that the Israelite women were popping them out so fast that it was impossible to reach any of them in time to kill the infant. God was pleased so we read,

And it came to pass, since the midwives feared God, He made houses for them — Exod. 1:21

You don’t know what “made houses” means? Did God come down and make them each a bungalow? Rabbis debated the mystery line, too. One of those midwives, you guessed it, was Miriam albeit by another name. Miriam’s cipher was Puah (Exodus 1:15), the reasons offered being many: one, she cooed at the babies (pu pu…); another, that the word suggesting weeping and wailing over the threat to Moses’ life; yet another drawing upon an indication that the word meant defiant resistance, her attitude against Pharaoh. (By this time you will not be the least surprised to learn that the other midwife was Miriam’s mother, Jochebed, but we’ll leave that explanation aside for now.)

So back to the reward:

Rav and Shmuel disagree. One said: Priestly houses, and one said: Royal houses. According to him who said priestly houses, this refers to Aaron and Moses, and according to him who said royal houses, David also came from Miriam, as it is written: “And Azubah died, and Caleb took Ephrath, and she bore Hur to him” (1 Chron. 2:19). And it is written: “And David was the son of that Ephrathite . . .” (1 Sam. 17:12). — Sotah 11b

And so it was.

Mother of a martyr

Josephus writes that Hur, the one who, with Aaron, held up Moses’ hands to defeat the Amalekites (Exodus 17:10-13), was Miriam’s husband (Antiquities III, 2, 4) but another view appears in later rabbinic literature: Miriam was the mother of Hur. From this perspective, we re-read 1 Chronicles 2 (quoted above) and notice that Hur was said to be the son of Caleb and Ephrath, the alternative name for Miriam.

Hur was said to be murdered by the worshippers of the Golden Calf. Here is one of the rabbinical passages explaining what happened:

When Moses had gone up [Mount Sinai], he had agreed with Israel to come down at the end of forty days. When he delayed coming down, all Israel came together to the elders. . . . They said to them, Moses agreed with us that he would come down in forty days. Now here it is forty days and he has not come down. And in addition, six hours more [have passed] . . . yet we do not know what has happened to him. So (in the words of Exod. 32:1 cont.) ‘Arise and make a god for us.’” When [the elders] heard that, [the elders] said to them, “Why are you angering Him, you for whom He performed all the miracles and wonders?” [But] they did not heed them and killed them. Then because Hur had stood . . . up to them with harsh words, they . . . rose up against him and killed him [as well]. Then all of Israel gathered around Aaron . . . — Midrash Tanchuma 3

And so they threatened Aaron unless he made the golden calf.

Grandmother of craftsman of the Tabernacle

Following the genealogy of the tradition above, Bezalel, “filled with the spirit”, the skilled craftsman responsible for all the decoration and furnishings of the Tabernacle, was the grandson of Miriam.

Then the Lord said to Moses, “See, I have chosen Bezalel son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah, and I have filled him with the Spirit of God, with wisdom, with understanding, with knowledge and with all kinds of skills— to make artistic designs for work in gold, silver and bronze, to cut and set stones, to work in wood, and to engage in all kinds of crafts. . . . — Exodus 31:1-5

We can’t prove a connection but it is interesting to wonder here about Jesus, son of Mary, a carpenter and builder of the church which in Christian literature was symbolized by the Tabernacle and Temple.

Miriam’s well

Again in Midrash Tanchuma Buber Bamidbar 2, we see that the rock that miraculously supplied water for Israel accompanied Israel in the wilderness because of Miriam. When Miriam died the same rock ceased to supply water. The original narrative may not have had any cause-effect relationship in mind but rabbis did see one. One of the functions of midrash was, after all, to create new narratives that tied adjacent episodes in the Bible. We are aware that biblical narratives tend to be collections of many smaller units strung together “like beads on a string” and so were the rabbis. Midrash was one imaginative way they had of making more coherent links between these beads but the links had to draw upon selected words or oddities in the texts to tie them together. Here is a midrashic explanation that tied the death of Miriam with the next episode that began with the Israelites complaining about lack of water:

. . . as stated (in Micah 6:4): AND I SENT MOSES, AARON, AND MIRIAM BEFORE YOU. Thus through their merit, Israel was sustained. The manna was through the merit of Moses. [You yourself know that it is so. When Moses passed away, what is written (in Josh. 5:12)? THE MANNA CEASED ON THE NEXT DAY (i.e., the day after Moses died).] The clouds of glory through the merit of Aaron. You yourself know that it is so. When Aaron passed away, what is written (in Numb. 21:4)? BUT THE TEMPER OF THE PEOPLE GREW SHORT ON THE WAY, because the sun was shining down upon them (without a cloud cover). And the well through the merit of Miriam, since it is stated (in Numb. 20:1-2): BUT MIRIAM DIED THERE. NOW THE CONGREGATION HAD NO WATER. And how was [the well] constructed? Like a kind of rock. It rolled along and came with them on the journeys. When the standards came to rest and the Tabernacle arose, the rock would come and settle down in the court of the Tent of Meeting. Then the princes would stand beside it and say (in the words of Numb. 21:17): RISE UP, O WELL; and the well would rise up.

To be finished in the next post.

Reiss, Moshe. “Miriam Rediscovered.” Jewish Bible Quarterly 38, no. 3 (2010): 183–90.

Steinmetz, Devora. “A Portrait of Miriam in Rabbinic Midrash.” Prooftexts 8, no. 1 (1988): 35–65.