Nanine Charbonnel’s thesis: Jesus of the gospels originated as a natural product of Jewish interpretation of their Scriptures and belief that the Divine Presence was to be found in the words of the Torah. The Oral Torah was understood to teach how to apply the Written Torah and Jesus was created as the personification of both. Jesus was also the personification of Israel, as earlier posts have demonstrated. Further, if the body of Israel itself was understood in certain quarters to have embodied the Torah (as there is some reason to believe) then the events of 70 CE have significant power to explain the death and resurrection narrative.

2. Personification of the Torah

2. Personification of the Torah

Making the Voice Visible — and Personified

How can one “see” a voice? We know that at Sinai the Israelites were said to have “seen” the voice of God. Here is a later rabbinic account of what the Jewish exegetes made of this passage in Exodus:

When the Holy One, blessed be He, gave the Torah at Sinai, He showed wonders of wonders to Israel. How is it? The Holy One, blessed be He would speak and the voice would go out and travel the whole world: . . . . And it is stated, “And all the people saw the sounds (literally, voices — Exodus 20:18)” – it is not written, “[voice],” here, but rather, “[voices].” Rabbi Yochanan said, “The voice would go out and divide into seventy voices for the seventy languages, so that all the nations would hear. — Exodus Rabbah 5:9

We recall Pentecost in Acts 2. We also recall the play on hearing and seeing when Paul hears a voice but does not see and when the Emmaus disciples hear the voice of Jesus but only “see” him as he vanishes.

For Nanine Charbonnel and her sources, there is nothing remarkably strange about Jewish interpreters imagining an incarnated voice or inventing a character to represent the word (and law and wisdom) of God.

A passage in Numbers may at a glance seem straightforward to many of us but it evoked serious commentary among Jewish exegetes:

When Moses went into the Tent of Meeting to speak with Him, he heard the voice addressing him from above the cover that was on top of the Ark of the Pact between the two cherubim — Numbers 7:89

The earliest Jewish commentary (Sifre) on this passage found much room for interpretation. God is obviously meant by “the voice” but the context of this verse is far removed from the mention of God. Azzan Yadin, cited by NC, explains:

Ha-katuv is essentially a rabbinic synonym for torah but with the difference that here it refers to Scripture as an agent that “acts” in a manner or “does” something in a way we imagine a person acting or doing — in this case “teaching” those it meets through reading and hearing.

The isolation of Numbers 7:89 from any context makes it impossible to link “with him” to God in a direct, grammatical sense, since God was last mentioned in Numbers 7:11, almost eighty verses earlier and is not the preceding noun. Since, grammatically speaking, neither the voice nor the pronominal “with him” necessarily refers to God, the assertion that the speaker in Numbers 7:89 is God is ultimately theological, not grammatical. The assertion is also common sense; after all, who but God would be speaking to Moses in the Tent of Meeting? But common sense is not always the best guide in these situations, so it is worth noting that from a strictly grammatical perspective, it is possible to read Numbers 7:89 as claiming that Moses entered the Tent of Meeting to speak with the same entity that spoke to him, namely “the voice,” understood as a divine intermediary.

Whether or not this is a plausible interpretation of Numbers 7:89 is not relevant to the present discussion. The argument is that (plausible or not) this is the interpretation found in the Sifre Numbers. Note how the biblical “voice” is picked up by the Sifre’s gloss:

Numbers 7:89 “When Moses went into the Tent of Meeting to speak with Him, he heard the voice …” Sifre Numbers “HA-KATUV [see box insert above] states that Moses would enter into the Tent of Meeting and stand there, and the voice descended from highest heavens to between the cherubs, and he heard the voice speaking to him from within.”

The Sifre Numbers is alive to God’s absence from Numbers 7:89 and reproduces this absence in the gloss — Moses hears “the voice” speaking in the Tent. More importantly, the Sifre provides additional information on the voice, information unrelated to the contradictory verses: upon Moses’ entry into the Tent of Meeting, the voice “descended from the highest heavens” — where it presumably resides at other times. If the intention of the [passage] were merely to argue that Moses encounters God inside the Tent of Meeting, why use a prooftext that does not mention God but only a voice, and then — compounding what should be an unfortunate omission — make no reference to God in the [passage] but rather pick up on the voice leitmotiv? Because that is precisely the point of the [passage]: a voice, a divine voice that regularly resides in the highest heavens, descends to speak with Moses in the Tent of Meeting, serving as an intermediary and thus allowing God to remain divorced from human affairs.

Can we imagine a voice, a voice alone, descending and speaking as a mediator with Moses? That is what is understood here.

The Incarnation as the Personification of Scripture

The Incarnation as the Personification of Scripture

Azzan Yadin is discussing the midrashic method of interpreting Scriptures that was practised by the rabbis from the late first to early second centuries CE, or from the era when the New Testament literature was in development. The name associated with this method was Rabbi Ishmael and Yadin’s discussion is found in Scripture as Logos: Rabbi Ishmael and the Origins of Midrash. I quote some interesting sections directly related to the personification of the Voice and Scripture.

The following section demonstrates how the rabbinic personification of the Law as a Teacher has remarkable affinities with the NT idea of Christ being the representative and teacher of the Law. What is most noteworthy here, for me, is the support for Nanine Charbonnel’s case that early Christian interpretations of Scripture grew out of Jewish interpretations that personified Scripture.

Thus Clement writes: “With the greatest clearness, accordingly, the Logos has spoken respecting Himself by Hosea: ‘I am your instructor’ (Hos 5:2).” Moreover, it is worth noting that Clement’s terminology is also similar to Rabbi Ishmael’s. For instance, Clement states that Christ’s coming could be known to the reader of the Hebrew Bible prior to the event since ή γραφή παιδαγωγήσει “the written [Scripture] will instruct [you].” The use of ήγραφή (the written) for Scripture is not common among early Christian writers. The singular η’ γραφή usually refers to a verse or phrase while the plural form at άι γραφαί (or άι’ιεραί γραφαί, the holy writings) refers to Scripture as a whole. Clement, however, regularly uses ή γραφή as Scripture. Coupled with the verbal predicate παιδαγωγήσει (will teach, or, will instruct), the result is strikingly similar to the “Ishmaelian” “ha-katuv [the written] teaches” ( הכתוב מלמד ).

The issue of Christ does, of course, represent a formidable theological boundary between Rabbi Ishmael and Clement, but should not obscure the very significant hermeneutical similarities. Clement’s full and consistent identification of the instructor with Christ marks him as the apogee of the Christos Didaskalos tradition; Rabbi Ishmael’s identification of the instructor with personified Scripture suggests a structurally similar Nomos [=Torah] Didaskalos tradition.

* * *

In his important article on Jewish binitarianism, Daniel Boyarin argues against the venerable idea that the Rabbis rejected divine intermediation in general and the Logos in particular. More accurately Boyarin shows that the eventual rejection is best understood against the backdrop of earlier shared theological traditions and language, largely excised from rabbinic literature, but still visible as a palimpsest beneath later editorial strata, or in rabbinically marginal works such as the Targumim. I would argue that the parallel between the understanding of Christ in the Christos Didaskalos tradition and Rabbi Ishmael’s representation of Scripture as personified teacher — Nomos Didaskalos — is part of such a shared reservoir of theological language and imagery.

88. See Edwin Luther Copeland, “Nomos as a Medium of Revelation, Paralleling Logos, in Ante-Nicene Christianity,” Studia Theologia 27 (1973): 51-61, whose discussion I follow.

91. Μ. J. Edwards, “Justin’s Logos and the Word of God,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 3 (1995): 261-80.

Clement and Justin Martyr, the outstanding representatives of the Christos Didaskalos tradition, are also key figures in the eventually discarded Christian tradition that emphasized the role of Nomos as a medium of revelation.88 This view is inherent in Clement’s positive assessment of the role of Torah as a revelation of the Logos, but also in his discussion of Christ. For example, Clement approvingly quotes from the Kerygma Petrou, stating: “Peter in his Preaching [kerygma] called the Lord Nomos and Logos,” and similarly, “in the Preaching of Peter you will find the Lord called Nomos and Logos.” This explicit identification of Christ as Nomos (Torah) is also found in Clement’s predecessor in the Christos Didaskalos tradition, Justin Martyr, who speaks of Christ as “the Son of God, who was proclaimed as about to come to all the world to be the everlasting law and the everlasting covenant.” Indeed, in his study of Justin’s Logos theology, M. J. Edwards argues that Justin drew more from the biblical and Jewish sources than from Plato and the Stoa.91 Edwards’s concluding remarks are extremely suggestive: “Our conclusion, therefore, is that… Christ is the Logos who personifies the Torah [Nomos, A. Y.]. In Jewish thought the Word was the source of being, the origin of the Law, the written Torah and a Person next to God. Early Christianity announced the incarnation of this Person, and Justin makes the further claims that Scripture is the parent of all truth among the nations, and that the Lord who is revealed to us in the New Testament is the author and the hermeneutic canon of the Old.“

Here we find many of the theological issues underpinning the Rabbi Ishmael midrashim: the personification of Scripture (Nomos), the Wisdom-derived idea of Scripture bringing truth to all the nations, and the hermeneutical contribution of personified Scripture that comes to teach the proper understanding of (for Rabbi Ishmael) Torah.

I am not arguing for outright identity here. There is no question that the Logos plays a much larger role in the theology of Clement and Justin than does the Nomos, and it also appears that the Nomos tradition is limited to Patristic authors with strong Palestinian ties. Justin was a native of Shechem, while Clement, who came to Alexandria from Athens, identifies his greatest teacher as a Palestinian thinker “of Hebrew origins.” Nonetheless, the use of Nomos as a category by which to describe Christ’s advent, along with the Nomos Didaskalos tradition in Rabbi Ishmael, and traces of Logos theology elsewhere, indicates that these categories circulated much more freely among early Christians and rabbis than is usually recognized. Shared theological categories may be viewed as evidence for rabbinic influence on the church fathers, or vice versa, but I suspect that this is not the proper historical model. It is widely recognized that Wisdom theology served as a model for Christ in the early church, and that Logos theology took over many Wisdom motifs. I have already argued (following Hirshman) that Rabbi Ishmael’s conception of personified Scripture may be linked to Ben Sira’s identification of Torah and Wisdom. In light of their shared genealogy, both the Logos Didaskalos and the Nomos Didaskalos may plausibly be seen as later developments of the personified Wisdom tradition, with each side adapting it to fit the evolving and still-inchoate needs of their respective communities.

Whether this is the best historical explanation remains to be seen. What has, I hope, been shown is that the Rabbi Ishmael midrashim are connected, albeit in different ways, to different communities and their attendant literary corpora, reflecting a historical reality in which the boundaries between these groups were not as fixed as they would become. The groups in question, rabbis, priests, Christians, did formulate exclusive identities and became separate (or extinct) communities. But the process was long, and even as they worked to establish and then seal their borders, the groups drew upon a shared reservoir of religious motifs and imagery, a broad religious koine, within which rabbinic literature is located. And it is in the context of this koine that rabbinic literature is best studied.

Kabbalistic ideas arguably originated in part, from pre-Talmudic times: see an earlier post where the origin of a few kabbalistic precepts was discussed; see also the previous post with updated links to Jeremiah and Ezekiel references. These sorts of ideas bring up an image of the Torah as a body and at the same time the body of Israel. From Gershom Scholem’s Zohar, The Book Of Splendour: Basic Readings from the Kabbalah . . . .

Thus the tales related in the Torah are simply her outer garments, and woe to the man who regards that outer garb as the Torah itself, for such a man will be deprived of portion in the next world. Thus David said: “Open Thou mine eyes, that I may behold wondrous things out of Thy law” {Ps. 119:18}, that is to say, the things that are underneath. See now. The most visible part of a man are the clothes that he has on, and they who lack understanding, when they look at the man, are apt not to see more in him than these clothes. In reality, however, it is the body of the man that constitutes the pride of his clothes, and his soul constitutes the pride of his body.

So it is with the Torah. Its narrations which relate to things of the world constitute the garments which clothe the body of the Torah; and that body is composed of the Torah’s precepts, gufey-torah {bodies, major principles}. People without understanding see only the narrations, the garment; those somewhat more penetrating see also the body. But the truly wise, those who serve the most high King and stood on mount Sinai, pierce all the way through to the soul, to the true Torah which is the root principle of all. These same will in the future be vouchsafed to penetrate to the very soul of the soul of the Torah.

See now how it is like this in the highest world, with garment, body, soul, and super-soul. The outer garments are the heavens and all therein, the body is the Community of Israel and it is the recipient of the soul, that is “the Glory of Israel”; and the soul of the soul is the Ancient Holy One. All of these are conjoined one within the other.

(Excerpt From: Gershom Scholem. “Zohar.” Apple Books. Highlighting added.)

Other Jewish writings identify the Torah with the sword of a warrior and a good wife.

In this light, look again at the figure of Jesus in Luke 4:16-21, “today, this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing” (v.21). Translating the commentary of Armand Abécassis,

In this light, look again at the figure of Jesus in Luke 4:16-21, “today, this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing” (v.21). Translating the commentary of Armand Abécassis,

That Sabbath, before the assembly gathered to bear witness, Jesus reads the prophetic text and interprets it because he knows its absolute meaning, since he lives it himself and is aware of what it manifests and what it conceals. The text is clear for him: he interprets it to say that he does not interpret it because he knows it in his body and in his soul. The text is fulfilled: what had been written up to now in search of himself would be given, visible, known, by Jesus for whom everything would be transparent. It is, consequently, such a being that one would have to follow, that one would have to hear and listen to. People would no longer need to refer to the divine word deposited in the Torah – a text – but to Jesus. This is why Luke thinks that, since Jesus is present, the Sabbath, in the synagogue, before the assembly of testimony that wants to learn to interpret, it becomes unnecessary to read the Torah. He would be the Torah incarnate.

The key point here is the extent to which we are seeing the text itself being understood as divine.

Neither Judaism nor Christianity is a religion of the Book. It is wrong to attribute this image to them. The Torah […] is something other than a book. It possesses a character of eternity and infinity, which makes us say that in it God has become or is becoming a text. Text and not book. As if God inhabited his text entirely, or rather his letter, in Greek gramma. Elsewhere I have used the word “ingrammation”, the verbal counterpart of “incarnation” in Christian doctrine. God is to the Torah in Judaism what he is, mutatis mutandis, to Christ in Christianity.

(translation of André Paul, Autrement la Bible. Mythe, politique et société, p. 255, cited by NC. Highlighting by NC)

NC’s midrashic hypothesis takes another tentative step by raising the possibility that the public life of Jesus in the gospels was based on the cycle of liturgical readings of Scripture. . . .

Three years of public life: is this not the personification of the three years of the liturgical cycle?

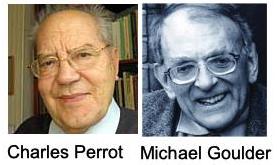

In NC’s suggestion, the public ministry of Jesus, according to the synoptic gospels, lasted three years. Here I do part company with NC. Surely the synoptic gospels indicate a one year ministry while it is the Gospel of John that points to at least three years. NC is leaning on the French scholar Charles Perrot who argued for a triennial liturgical cycle for the reading of the Pentateuch in the Palestinian synagogues of the time. I cannot comment on the reliability of this finding since the British scholar Michael Goulder, (not referenced by NC) has disputed Perrot’s findings, and I have little appetite for taking time out to investigate all the data-bits that are the grist for that debate. Goulder, followed by Spong, postulated a one year liturgical reading for the Gospels of Matthew and Luke to coincide with the one year synagogue readings of Scripture. Happily, in my view, NC added a question mark to the idea.

In NC’s suggestion, the public ministry of Jesus, according to the synoptic gospels, lasted three years. Here I do part company with NC. Surely the synoptic gospels indicate a one year ministry while it is the Gospel of John that points to at least three years. NC is leaning on the French scholar Charles Perrot who argued for a triennial liturgical cycle for the reading of the Pentateuch in the Palestinian synagogues of the time. I cannot comment on the reliability of this finding since the British scholar Michael Goulder, (not referenced by NC) has disputed Perrot’s findings, and I have little appetite for taking time out to investigate all the data-bits that are the grist for that debate. Goulder, followed by Spong, postulated a one year liturgical reading for the Gospels of Matthew and Luke to coincide with the one year synagogue readings of Scripture. Happily, in my view, NC added a question mark to the idea.

Role of the Prophets

Now among those Jewish exegetes who were to give rise to Christianity, the Torah, meaning here the Pentateuch (the five books of Moses), was originally interpreted by reference to the Prophets, NC writes. It was later that rabbis forbade that method of interpretation and required that a difficult passage in the Torah be interpreted only by reference to other (clearer) Torah verses. Was this prohibition a reaction against the kind of midrashic interpretation that led to the rise of Christianity?

Early Jewish-Christian exchanges

While exploring around this rabbinic passage I came across another work, one not cited by NC, that appears to add support to NC’s discussion: Brothers Estranged: Heresy, Christianity, and Jewish Identity in Late Antiquity by Adiel Schremer. In Schremer’s view, a rabbinic text about a Jewish heretic who was healing and teaching in the name of Jesus dates from as early as the second century. Schremer’s reasons for this early date:

- the point of the story is to address “the question of whether the followers of Jesus should be considered, too, as minim [heretics]” — in other words, the matter was not yet unanimously settled;

- the names of the rabbis populating the story all belong to the second century;

- the story implies a time early enough for when Judaism felt threatened by the “Christian heresy”.

Here are the rabbinic texts:

I. There was a case with Rabbi Elazar ben Dama, who was bitten by a snake, and Jacob of Kefar Sama came to heal him in the name of Jesus son of Pantera ( ישוע בן פנטרא ), and Rabbi Ishmael did not allow him. They [sic; read: he] said to him: “You are not permitted, Ben Dama!” He said to him: “I shall bring you proof that he may heal me,” but he did not manage to bring the proof before he died. Said Rabbi Ishmael: Happy are you, Ben Dama, for you have expired in peace, and you did not break down the hedge of the Sages. For whoever breaks down the hedge of the Sages calamity befalls him, as it is said: “He who breaks down a hedge is bitten by a snake” (Eccl. 10:8).

II. There was a case with Rabbi Eliezer, who was arrested (literally: caught) on account of minut [=heresy], and they brought him up to the bema (tribunal) for judgment. That hegemon (governor) said to him: Should an elder of your standing occupy himself in these matters?! He said to him: I consider the Judge [sic] as trustworthy. That hegemon supposed that he referred to him, but he referred only to his Father in heaven. He said to him: Since you have deemed me reliable for yourself, I too have said [to myself]: Is it possible that these gray hairs should err in such matters?! [Surely not!] Dimissus, lo you are released. And when he left the court he was distressed to have been arrested on account of matters of minut. His disciples came in to comfort him but he was not convinced (literally: he did not accept [their words of comfort]). Rabbi Aqiva entered and said to him: Rabbi, May I say something to you so that you will not be distressed? He said to him: Speak! He said to him: Perhaps some one of the minim told you a teaching of minut that pleased you? He said to him: By Heaven! You reminded me! Once I was strolling in the street of Sepphoris. I bumped into (literally: I found) Jacob of Kefar Sikhnin, and he said a teaching of minut in the name of Jesus son of Pantiri (ישוע בן פנטירי), and it pleased me. And I was arrested on account of matters of minut, for I transgressed the teachings of Torah: “Keep your way far from her and do not go near the door of her house” (Prov. 5:8–7:26). For Rabbi Eliezer did teach: “One should always flee from what is ugly and from whatever appears to be ugly.”

Torah is the Divine Presence

Early rabbinic writings explicitly say that the Torah is the Divine Presence:

Whoever studies Torah at night is face to face with the Divine presence, for it is said [Ps 16:8] : I have the Lord constantly before my eyes, and also [Lam. 2:19] : Arise, cry out at the entrance of the night watches, in the Presence of the Lord.

— Tamid 32b (the text quoted here is translated from version in Jésus & Virounèka by Marie Vidal, p. 82)

The idea of an incarnate Son of God is therefore a natural product of some basic elements of Judaism. God is “ingrammated” (becomes the text), is found and met within the text of the Torah. God is present as Torah in his earthly dwelling of the Tent or Tabernacle.

Then with the catastrophic events of 70 CE that saw the massacre of Israel, also conceptualized as the Son of God, it was surely almost inevitable that a Christ-Son of God was imagined to have been slain and resurrected.

NC rightly adds, p. 345

Il est fort intéressant de noter que des Pères de l’Église furent encore très attentifs à ces équivalences.

=

It is very interesting to note that the Fathers of the Church were still very attentive to these equivalences.

Christian identity of Gospels with Body

Church Fathers frequently expressed metaphors and similes that may strike many of us today as over the top, yet they may in fact be expressions of ideas that were closer to the matrix from which the New Testament writings emerged.

Thus Hippolytus of Rome (around 204) is found to express this same idea the equivalence of Scripture and Christ, in this case Christ crucified:

And see, O man, the things that in old time were sealed up, and could not be known, are now openly proclaimed upon the housetops, and the Book of Life has been unfolded, being stretched out visibly upon wood [= a cross, allusion to tree of life], having a title written in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew [John 19:20], so that both Romans and Greeks and Hebrews might be taught, in order that men looking for the good things that are coming may believe the things that are written in this Book of Life . . .

And Origen, as quoted by Jerome:

We read the Holy Scriptures. I believe that the Gospel is the Body of Christ. I believe that the holy Scriptures are his teaching. And when he says: he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood (Jn 6,53), although these words can also refer to the [Eucharistic] Mystery, yet the Body and Blood of Christ is truly a word of Scripture, the teaching of God. When we are about to receive the [Eucharistic] Mystery, if even a tiny crumb falls, we feel lost. When we are listening to God’s Word, when our ears perceive the Word of God and the body and blood of Christ, what great danger would we not fall into were we to think about something else?

(74 Omelie sul Libro dei Salmi, Milano 1993, pp. 543-544 — from Papal Commentary (link is to PDF)).

Later in medieval times, Pierre Bersuire:

For Christ is a sort of book written into the skin of the virgin . . . . That book was spoken in the disposition of the Father, written in the conception of the mother, exposited in the clarification of the nativity, corrected in the passion, erased in the flagellation, punctuated in the imprint of the wounds, adorned in the crucifixion above the pulpit, illuminated in the outpouring of blood, bound in the resurrection, and examined in the ascension.

(Pierre Bersuire, Repertorium morale, quoted by Gellrich, p. 17)

From the seventeenth century, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet turns back to Origen’s understanding of the Gospel:

That is why the great Origen was not afraid to assure us that the word of the Gospel is a kind of second body that the Savior took for our salvation: Partis quem Dominus corpus suum esse dicit, verbum est nutritorium animarum (In Matth., Commentar., n. 85). What is the meaning of this, Christians, and what resemblance could he find between the body of our Savior and the word of his Gospel? This is the essence of this thought: it is that eternal Wisdom, who is begotten in the bosom of the Father, has made himself perceptible [french, “sensible”] in two ways. He made himself perceptible in the flesh he took in the womb of Mary; and he still makes himself perceptible through the divine Scriptures and through the word of the Gospel: so much so that we can say that this word and these Scriptures are like a second body that he takes on, in order to appear again before our eyes. It is there that we see it: this Jesus, who conversed with the apostles, still lives for us in his Gospel, and he still pours out the word of eternal life for our salvation.

–o0o–

Next post, 3. The Incarnation of the Two Torahs, Written and Oral

Abécassis, Armand. “En vérité je vous le dis”: Une lecture juive des évangiles. Paris: NUMERO UN, 1999.

Bonnard, Pierre E. La Sagesse en personne annoncee et venue, Jesus Christ. Paris : Editions du Cerf, 1966. http://archive.org/details/lasagesseenperso0000bonn.

Maxence Caron – Le Site officiel. “Bossuet : Le Panégyrique de Saint Paul,” June 15, 2010. https://maxencecaron.fr/2010/06/bossuet-le-panegyrique-de-saint-paul/.

Charbonnel, Nanine. Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier. Paris: Berg International éditeurs, 2017.

Gellrich, Jesse M. Idea of the Book in the Middle Ages: Language Theory, Mythology, and Fiction. Ithaca, NY: NCROL, 1985.

Hippolytus, Antipope, Basilios Georgiades, and J. H. Kennedy. Part of the Commentary of S. Hippolytus on Daniel : Lately Discovered by Dr. Basilios Georgiades. Dublin : Hodges, Figgis, 1888. http://archive.org/details/partofcommentary00hipp.

Oblates of St. Benedict: Papal Commentary on the Psalms. “Psalm 147:12-20(147).” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://oblatesosbbelmont.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Psalm-147B.pdf.

Scholem, Gershom . Zohar, The Book Of Splendour: Basic Readings from the Kabbalah. New York: Schocken Books, 1949.

Schremer, Adiel. Brothers Estranged Heresy, Christianity and Jewish Identity in Late Antiquity. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Yadin, Azzan. Scripture as Logos: Rabbi Ishmael and the Origins of Midrash. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004. https://www.scribd.com/book/420408237/Scripture-as-Logos-Rabbi-Ishmael-and-the-Origins-of-Midrash.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

On seeing/hearing and the Emmaus disciples: the intermediary metaphor is food, particularly bread and fish. It is not simply that the disciples see Jesus as he vanishes, but that he becomes suddenly recognizable to them upon the breaking of bread. Lk 24:30-31, 35. The loaves and fishes miracle illustrates that man does not live by bread alone, etc. Word=bread=life/sight, etc. As the incarnate Word, Jesus is essentially his words, and we hear if we have ears, but we also live/see/eat only through Jesus. So we have these recurring binary metaphors in the gospels about sight/blindness; hunger/food; life/death, etc. Jesus always represents sight (the Light), food (the eucharist), and life (resurrection). But he is a remarkably non-visual character. There are no physical descriptions of him in any canonized Scripture. We have only rare references to items of clothing, or sandals, or bare feet.

Bread is a symbol of the Word, too. Interesting, perhaps, that as the disciples break bread they recognize Jesus — who bodily vanishes as if his bodily presence is no longer needed. His bodily presence has fulfilled its function in the breaking of bread — the sharing and partaking of the word.