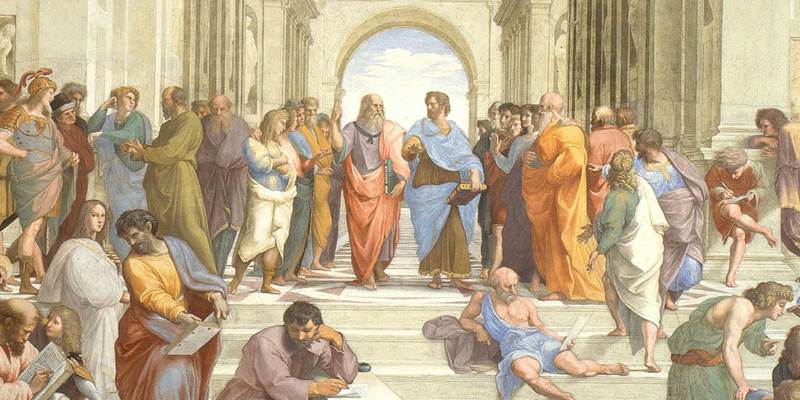

Think of the world from which Christianity emerged and mystery religions easily come to mind. That may be a mistake. A more relevant context, influencers and rivals were the popular philosophers and their schools in the first and second centuries.

The Jew and the Christian offered religions as we understand religion; the others offered cults; but their contemporaries did not expect anything more than cults from them and looked to philosophy for guidance in conduct and for a scheme of the universe. (Nock, Conversion, 16)

Any philosophy of the time set up a standard of values different from those of the world outside and could serve as a stimulus to a stern life, and therefore to something like conversion when it came to a man living carelessly. (Nock, 173)

Further, this idea was not thought of as a matter of purely intellectual conviction. The philosopher commonly said not ‘Follow my arguments one by one: . . . but . . . Believe me, those who express the other view deceive you and argue you out of what is right.’ (Nock, 181)

A mystery evoked a strong emotional response and touched the soul deeply for a time, but [conversion to] philosophy was able both to turn men from evil and to hold before them a good, perhaps never to be attained, but presenting a permanent object of desire to which one seemed to draw gradually nearer. (Nock, 185)

As an introduction to the view that popular philosophers had a more profound role than mystery cults in shaping Christianity, I’ve distilled biographical details from one ancient biographer of those philosophers. Spot the similarities to what we read about Jesus and Paul.

Follow Me

Socrates

Socrates met Xenophon in a narrow passage way and accosted him with questions. Xenophon was confused, so Socrates told him, “Follow me and learn”, and from that moment on Xenophon became his disciple.

Diogenes

Someone came to Diogenes and asked him to tell him how to live, what do do …. Diogenes told him to “follow him”. Unfortunately Diogenes also imposed a humbling condition on the would-be follower who was too embarrassed to comply.

Zeno

Now the way he came across Crates was this. He was shipwrecked on a voyage from Phoenicia to Peiraeus with a cargo of purple. He went up into Athens and sat down in a bookseller’s shop, being then a man of thirty. As he went on reading the second book of Xenophon’s Memorabilia, he was so pleased that he inquired where men like Socrates were to be found. Crates passed by in the nick of time, so the bookseller pointed to him and said, “Follow yonder man.” From that day he became Crates’s pupil.

Ethical Teachings and Example, a Physician of Souls

Chilon

“I know how to submit to injustice and you do not.”

The tale is also told that he inquired of Aesop what Zeus was doing and received the answer: “He is humbling the proud and exalting the humble.”

Not to abuse our neighbours

Do not use threats to any one.

When strong, be merciful.

Let not your tongue outrun your thought. Control anger.

Pittacus

Mercy is better than vengeance

Speak no ill of a friend, nor even of an enemy

Cleobulus

we should render a service to a friend to bind him closer to us, and to an enemy in order to make a friend of him.

Aristippus

He bore with Dionysius when he spat on him,

The sick need the physician, not the well

Aristippus

When Dionysius inquired what was the reason that philosophers go to rich men’s houses, while rich men no longer visit philosophers, his reply was that “the one know what they need while the other do not.”

In answer to one who remarked that he always saw philosophers at rich men’s doors, he said, “So, too, physicians are in attendance on those who are sick, but no one for that reason would prefer being sick to being a physician.”

Dionysius was offended and made him recline at the end of the table. And Aristippus said, “You must have wished to confer distinction on the last place.”

Stilpo

And conversing upon the duty of doing good to men he made such an impression on the king that he became eager to hear him.

Plato

If Phoebus did not cause Plato to be born in Greece, how came it that he healed the minds of men by letters? As the god’s son Asclepius is a healer of the body, so is Plato of the immortal soul.

Bion

He used repeatedly to say that to grant favours to another was preferable to enjoying the favours of others.

The road to Hades, he used to say, was easy to travel.

Aristotle

To the question how we should behave to friends, he answered, “As we should wish them to behave to us.”

Antisthenes

“It is a royal privilege to do good and be ill spoken of.”

When a friend complained to him that he had lost his notes, “You should have inscribed them,” said he, “on your mind instead of on paper.” As iron is eaten away by rust, so, said he, the envious are consumed by their own passion. Those who would fain be immortal must, he declared, live piously and justly.

“Many men praise you,” said one. “Why, what wrong have I done?” was his rejoinder

Diogenes

The love of money he declared to be mother-city of all evils.

Good men he called images of the gods

all things are the property of the wise

Zeno

A Rhodian, who was handsome and rich, but nothing more, insisted on joining his class. but so unwelcome was this pupil, that first of all Zeno made him sit on the benches that were dusty, that he might soil his cloak, and then he consigned him to the place where the beggars sat, that he might rub shoulders with their rags. So at last the young man went away.

This man adopts a new philosophy. He teaches to go hungry: yet he gets Disciples.

Cleanthes

Afterwards when the poet apologized for the insult, he accepted the apology, saying that, when Dionysus and Heracles were ridiculed by the poets without getting angry, it would be absurd for him to be annoyed at casual abuse.

Pythagoras

Pythagoras made many into good men and true

Epicurus

He carried deference to others to such excess that he did not even enter public life.

He showed dauntless courage in meeting troubles and death

He would punish neither slave nor free man in anger. Admonition he used to call “setting right.”

Not to call the gods to witness, man’s duty being rather to strive to make his own word carry conviction

God takes thought for man

In storm at sea

Bias

He was once on a voyage with some impious men; and, when a storm was encountered, even they began to call upon the gods for help. “Peace!” said he, “lest they hear and become aware that you are here in the ship.”

Aristippus

It happened once that he set sail for Corinth and, being overtaken by a storm, he was in great consternation. Some one said, “We plain men are not alarmed, and are you philosophers turned cowards?” To this he replied, “The lives at stake in the two cases are not comparable.”

Pyrrho

When his fellow passengers on board a ship were all unnerved by a storm, he kept calm and confident, pointing to a little pig in the ship that went on eating, and telling them that such was the unperturbed state in which the wise man should keep himself.

Divinely called, taught God’s truths, believed to be Divine

Continue reading “Jesus (and Paul) in the Ancient Philosopher Tradition”