.

This post continues from The Author of the So-Called Ignatians was an Apellean Christian

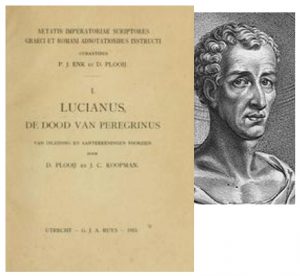

TDOP = The Death of Peregrinus by Lucian. Harmon’s translation here.

| Links to all posts in this series are collated at: Roger Parvus: Letters Supposedly Written by Ignatius

|

.

| In the letters of Peregrinus there are some passages that concern his gospel. If, as I have proposed, he was an Apellean Christian, we can expect to find here too some rough-edged and clumsy corrections by his proto-Catholic editor/interpolator. |

.

—0O0—

TO THE PHILADELPHIANS 8:2 – 9:2

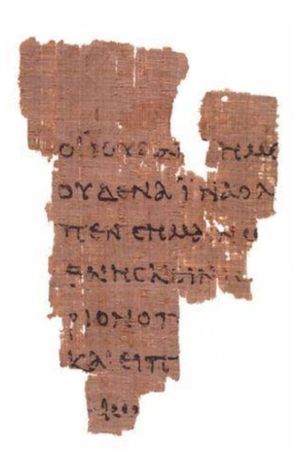

8:2. But I exhort you to do nothing in a spirit of faction—instead, in accordance with the teachings of Christ. For I heard some saying, “If I do not find [in] the archives in the gospel I do not believe.” And when I said to them, “It is written,” they responded, “That is what is in question.”

But my archives are Jesus Christ; the inviolable archives are his cross, his death, his resurrection, and the faith which is through him. It is by these that I desire to be justified, with the help of your prayers.

[9:1. The priests are good, but better is the high priest who has been entrusted with the holy of holies; he alone has been entrusted with the secrets of God. He is himself the door of the Father, through which enter in Abraham and Isaac and Jacob, and the prophets and the apostles and the church. All these combine in the unity of God.

9:2. Nevertheless]

The gospel has a distinction all its own, namely the appearing of the Savior, our Lord Jesus Christ, his suffering and his resurrection.

[For the beloved prophets announced him, but the Gospel is the completion of imperishability. All these things are good, if you believe with love.]

The above passage begins by relating part of an exchange the prisoner had with his Judaizing opponents. There is almost universal agreement that the “archives” in the second sentence refers to the Old Testament. And most scholars are in agreement as to the general sense of the verse: The Judaizers were Christians but insisted that the gospel meet some Old Testament-related requirement of theirs. But beyond that, there has been much debate about the punctuation and precise interpretation of the verse. The biggest problem is that at face value it seems to say that if the Judaizers’ requirement is not met they do not believe in the gospel.

The above passage begins by relating part of an exchange the prisoner had with his Judaizing opponents. There is almost universal agreement that the “archives” in the second sentence refers to the Old Testament. And most scholars are in agreement as to the general sense of the verse: The Judaizers were Christians but insisted that the gospel meet some Old Testament-related requirement of theirs. But beyond that, there has been much debate about the punctuation and precise interpretation of the verse. The biggest problem is that at face value it seems to say that if the Judaizers’ requirement is not met they do not believe in the gospel.

It seems incredible that Christians would not believe in the gospel. So, to avoid such a radical interpretation, a number of alterations have been proposed.

Some have wanted to simply delete the words “in the gospel” as a later gloss. Others, to arrive at the same result by another route, argue that the verse in question contains implied words that are lost in a literal translation. William Schoedel for example, proposes that

“the object (‘it’) should be supplied in the second part of the sentence just as it is in the first. And something like the verb ‘to be’ (or ‘to be found’) can also easily be supplied” (Ignatius of Antioch, pp. 207-8).

Thus Schoedel’s translation is:

“If I do not find (it) in the archives, I do not believe (it to be) in the gospel.”

In this way the Judaizers are made to reject only those parts of the gospel that are not found in the Old Testament. Michael Goulder, for one, considers that solution “implausible” (“Ignatius’ ‘Docetists’” in Vigiliae Christianae, 53, p. 17, n. 4), but to Schoedel it is definitely preferable to accepting at face value the statement that the Judaizing Christians do not believe in the gospel.

He writes: Continue reading “The (Apellean) Gospel of Peregrinus”