Having surveyed what the archaeological evidence tells us about religious practices of the Judeans in Elephantine (see the previous post) let’s now compare the evidence for Judah and Samaria in the same period. This time I am quoting only two sources, a chapter by Reinhard G. Kratz in A Companion to the Achaemenid Empire and a refreshingly new perspective from Annette Yoshiko Reed in her book Demons, Angels, and Writing in Ancient Judaism.

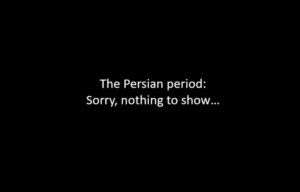

We saw in the Elephantine post the slide that sums up all that archaeology has given us and it’s nix. But Kratz finds a few epigraphical sources before turning to the biblical literature.

Epigraphical Sources

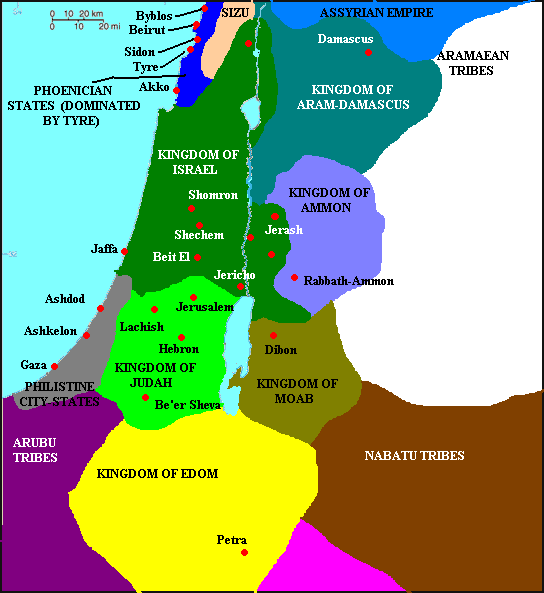

Inscribed stamps and seals attest to some external trade. They inform us that the region was called Yehud (yh, yhd, yhwd). Names of some governors are preserved. Samaria and Elephantine were fortress centres (p. 136) so Kratz suggests we can assume the administrative centre of Yehud was also a fortress. (He may be nudged to make that comparison because that is what Nehemiah 2:8; 7:2 attests.) On the basis of the Elephantine letters we can conclude that Jerusalem had a high priest and other priests as well as nobles and other officials.

There is a coin depicting a deity on a winged wheel. Not quite what we expected to find from the land of Ezra and Nehemiah.

We learn something of the ethnic makeup of the population from ostraca inscribed with personal names. There are names containing a form of Yhwh and El, as well as Aramaic, Phoenician, Edomite and Arabian personal and divine names. Three temples or sanctuaries are also mentioned: The Temple/House of Uzzah, … of Yahu, … of Nabu.

Apparently the cultic worship of the Judean‐Samarian deity Yahu was not limited to the “place that Yhwh will chose” (Deut. 12) during the fourth century BCE. The historical constellation represented in the epigraphic material appears not to differ from the one of the Judeans at Elephantine … or from the (Israelite) worshippers of Yhwh in the Province of Samaria. (Kratz 135)

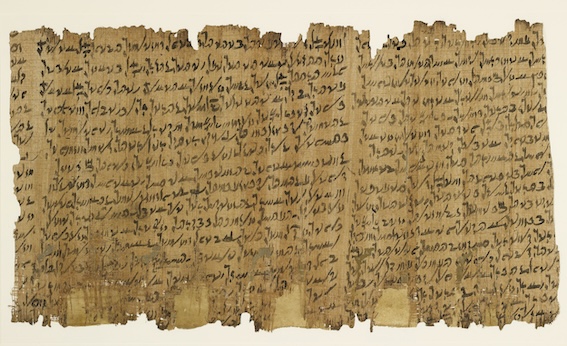

North of Jericho have been found papyri that are . . .

. . . private deeds that first and foremost deal with the selling of slaves . . . The clay bullae and coins are of interest because of their iconography. Here too, the minting shows different (Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Persian, and Greek) cultural influences and motifs, amongst them representations of deities and naked men. Especially significant is a coin that shows a portrait and inscription of the god Zeus on one side and has a Yahwistic name on the reverse . . . (p. 135)

In Samaria….

Here we have – especially amongst the owners, contractual partners, and slaves – mostly Israelite‐Judean names; next to them and especially amongst the witnesses for the deeds and the officials there exists a plethora of Aramaic, Phoenician, Edomite, Akkadian, and Persian names. . . . [T[he situation is reminiscent of the situation in Judah and Elephantine and implies the same historical constellation: we learn of a coexistence and cooperation of several ethnicities within the political structures of the Persian Empire. These ethnicities do not define their identity by a strict separation from each other; rather, they live side by side . . . (pp 135f)

How can we know if “Samaria” was known as such?

The name Samaria is attested in its long form (šmryn/šmrn) as well as in abbreviations (šmr, šm, šn, š). The Persian satrapy of Transeuphrates is the superordinated political unit. Its satrap Mazaios/Masdaj is mentioned by its full name or in abbreviated form (mz) on coins: “Mazday who resides over Ebir‐nari and Cilicia” (mzdy zy ʿl ʿbr nhra wh. lk). Samaria itself had the status of a province (šmryn mdyntʾ) and was ruled by a governor (ph. t šmryn/šmrn). The capital is called a “fortress” (šmryn byrtʾ). In accordance to this terminology, the papyri are written “in the fortress Samaria (that is) in the Province of Samaria.” Coins mention a prefect (sgnʾ) and judges (dynʾ) as subordinate officials. (136)

And that’s about it for the epigraphical evidence relating to Judea and Samaria in Persian times on the basis of epigraphical sources.

Literary Sources

Kratz next turns to literary sources. It’s not looking good for those of us who are looking for independent evidence of the biblical narrative:

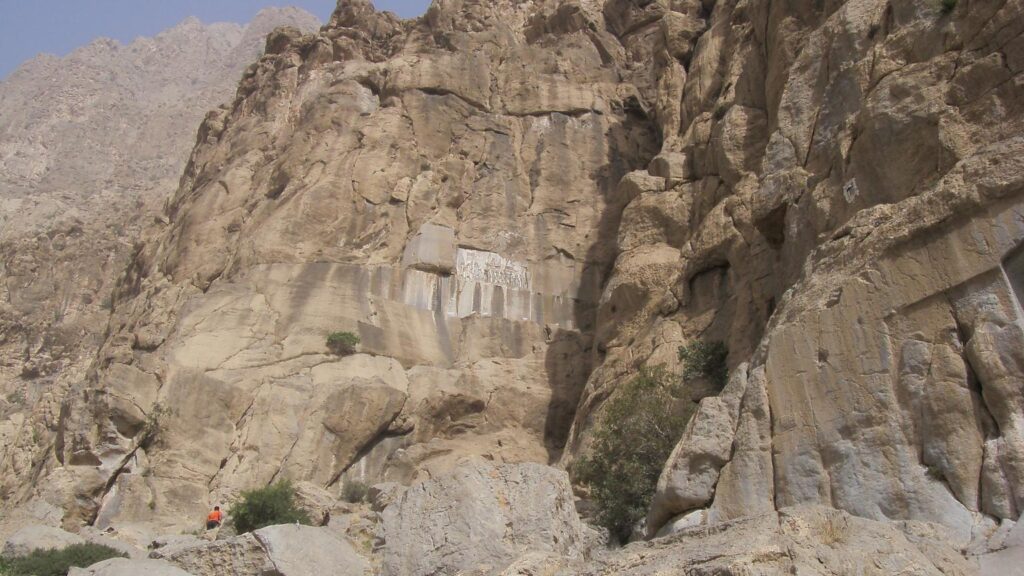

Literary sources that are attested archeologically in the Achaemenid period are only known to us from Elephantine: Here we have the “Words of Ahiqar” and an Aramaic version of the Bisitun inscription …. Otherwise we have to rely entirely on the biblical tradition and on the tradition dependent on it, such as the Jewish Antiquities of Flavius Josephus. (137)

While the literary sources from Elephantine fit well with what is dug up in Judah and Samaria, the biblical writing become something of an outlier:

In contrast to the literary works from Elephantine that fit well into the picture reflected by the epigraphic material, the biblical tradition contains a series of particularities. (137)

Everything we read in the Bible about this period appears to be at war with what we find in the ground:

Rather, the Bible seems to be highly critical toward the historical situation and even rejects it by creating its own religious counter‐world, a world that centers on the Torah of Moses and/or the biblical prophets . . . (137)

So what can the scholar honestly say about the facts of the Persian period Jehud and Samaria?

Here, one has to accept that one will hardly ever reach beyond a well (or less well) argued hypothesis. (138)

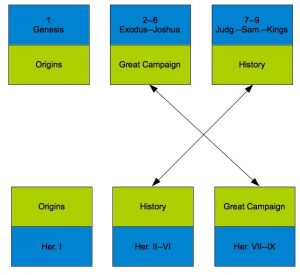

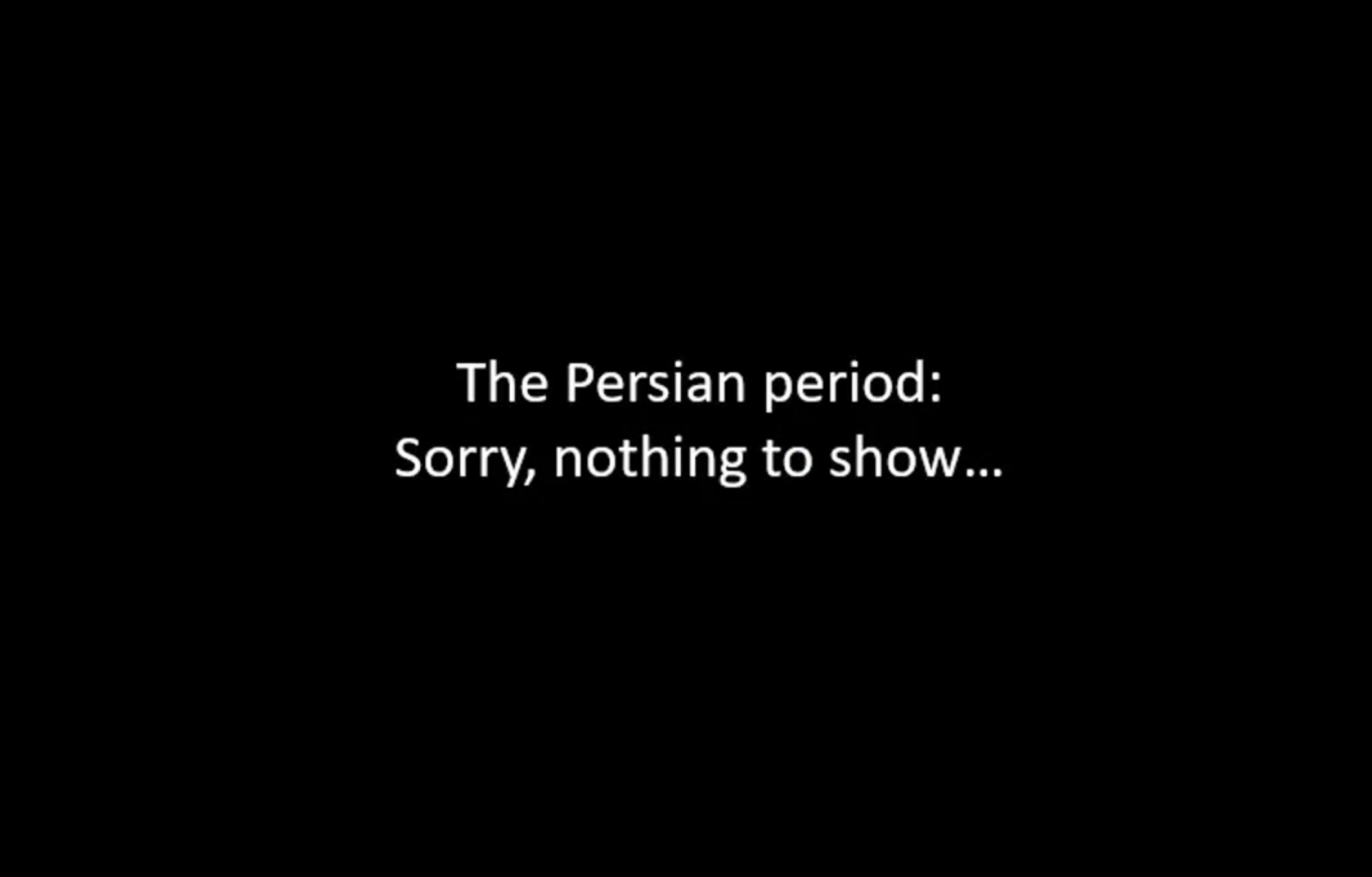

Kratz divides up the literary sources into two groups:

1. Writings set in the Persian period but not necessarily written so early:

- Ezra-Nehemiah

- 1 Esdras

- Esther

- Isaiah 44-45

- Haggai

- Zechariah

- Daniel

In these writings the roughly 200 years of Persian rule over Judah and Samaria are condensed to three – if we add Esther, four – events:

(i) the end of the Babylonian exile and the rebuilding of the temple under Cyrus and Darius (2Chron. 36; Ezra 1–6 and 1 Esd.; Isa 44:28–45:13; Hag.; Zech. 1–8; Dan. 1;6 and 8–11);

(ii) the mission of Ezra under Artaxerxes (Ezra 7–10; Neh. 8; 1 Esd.);

(iii) the mission of Nehemiah under Artaxerxes (Neh. 1–13);

(iv) the rescue of the Jewish people under Xerxes (Esther).

(138 – my formatting)

Kratz claims that two of the above events find a point in actual history:

- the rebuilding of the second temple

- the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem

However, Kratz provides no evidence to support his declaration that these events at this time are “actual history”. As far as I can see he has relied entirely on the assumption that the unprovenanced biblical narratives relate genuine historical events.

Kratz again:

Two – possibly authentic – prophetic oracles from the time of the reconstruction of the temple have come down to us and are now incorporated into the book of Haggai: Hag 1:1.4.8 and 1:15–2:1.3.9a. (138)

But he is surely aware of the thin ice on which he stands:

Both prophetic books [i.e. Haggai and Zechariah] contain some Persian flavor, but we cannot derive reliable historical information from them. Even the role of Serubbabel and Joshua remains unclear as they both appear only in secondary, i.e. later, passages . . . . The same has to be said of the figure of Sheshbazzar, who is mentioned only in Ezra 1:7–11 and Ezra 5:14–16 (6:5?) and who cannot be placed historically . . . . (138)

Kratz assigned other writings such as sections of Isaiah to the Persian period. What historical value do they have?

The oracles in Isaiah 44–45 . . . , the narrative in Ezra 1–6 and 1 Esdras . . . , as well as the literary reflexes on the beginnings of Persian rule in the book of Daniel . . . , have to be seen as later literary creations that have little historical value. (138)

What about Ezra 5-6 that seems at face value to be “so historical”?

A comparison of the Aramaic narrative in Ezra 5–6 – which is the literary nucleus of Ezra 1–6 where we find the older variant of the two versions of the famous edict of Cyrus (Ezra 1,1–4; 6,1–5) – with the papyri from Elephantine shows that this narrative appears to work with general historical knowledge and contains quite a bit of the flavor of the time. This, however, does not imply that the material has to be regarded as historical. Rather, Ezra 5–6 are written in the spirit of the biblical tradition and they are indebted to the Chronistic view of history (Kratz 2006). (139)

What about Nehemiah?

All the other passages of the book of Nehemiah, including those designating Nehemiah as “governor” (Neh. 5:1419; 12:26), are secondary literary supplements that were added to the building report in order to integrate Nehemiah into the (biblical) sacred history of the people of Israel, i.e. the people of God. Their historical appraisal stands on very shaky ground. (139)

Kratz acknowledges the crux of finding a way to prise history from Ezra-Nehemiah.

The evaluation of the mission of Ezra, reported in Ezra 7–10 and Neh 8–10, is most difficult . . . . His mission too is dated to the reign of a king called Artaxerxes. Scholarship generally identifies this king with Artaxerxes II since Nehemiah does not seem to presuppose Ezra. Such a dating operates on the premise that the Ezra memoir existed independently and is historical. This approach blends the historical and literary levels of the narrative. The historical fiction of the biblical tradition emphasizes that the same Artaxerxes is meant here. Ezra and Nehemiah are supposed to be contemporaries in order to complete the restitution of the people of Israel in the Province of Judah in accordance with the Mosaic law . . . Only in literary‐historical terms Ezra is younger than Nehemiah. (139)

We would love books that look like history to yield genuine history but we can’t always have what we want:

Historically, however, we can say little about Ezra. The Aramaic rescript in Ezra 7 forms the literary kernel of the Ezra narrative: Apart from bringing donations to Judah, Ezra is ordered to ensure the execution of the law (dat) of the Jewish God, that is identical to the law (dat) of the king, in the territory of Transeuphrates. The Hebrew narrative in which Ezra executes this order (Ezra 8–10; Neh. 8–10) is dependent on this rescript. The authenticity of the Aramaic rescript that once again is a mixture of Persian period flavor and biblical topoi continues to be disputed since the time of Eduard Meyer and Julius Wellhausen . . . . Despite the ongoing debate the authenticity is unlikely (Schwiderski 2000; Grätz 2004). The text reads like a foundation legend of the legal status of the Torah of Moses in Judaism and is comparable to the Letter of Aristeas reporting the origin of the Greek translation of the Torah in Alexandria under Ptolemy II. The historical background of the Ezra legend is probably the experience of the growing dissemination of the Torah as binding commitment in Judah and Samaria; this dissemination possibly started during the Persian period but came to full effect only in Hellenistic times. (139f)

What history can be gleaned from the book of Esther?

The book of Esther displays an extraordinary familiarity with details of the Persian court – commentaries generally quote the corresponding parallels from Herodotus and Xenophon. This general knowledge is supplemented with all kinds of fantastic details such as the marriage of the Xerxes to the Jewess Esther and woven into a narrative that portraits – in recourse to the biblical tradition – the situation of the Jews in the eastern diaspora . . . . (140)

In brief: it is a romantic novel that echoes Greek writing.

Kratz reminds us of what we should not need to be reminded. The fact that he says it at all is a regrettable commentary on so much traditional biblical scholarship:

The book of Esther is an instructive example that one should not use the flavor of a time to argue for the historicity of the events narrated or to deduce from it a date for the literary origin of the story. (140f)

That principle, Kratz notes, should also be applied to the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Yet by far most discussions of Ezra-Nehemiah that I have encountered assume without question that those narratives are Persian era documents with historical underlay.

The example of Esther should also be used in the interpretation of Ezra‐Nehemiah. In both cases the Greek versions . . . . show that the legends about Israelites and Judeans during the Persian period – legends on which the self‐understanding of Judaism rests – were still relevant during Hellenistic times and were spun out further. (141)

To be a little more precise, it would be better to remove the qualifier “still” from “relevant” in the above. There is no evidence that they were ever relevant in the Persian era. The evidence we have surveyed testifies against the stories of Ezra-Nehemiah having any relevance in the Persian period.

2. Biblical sources dated to Persian times

This dating is a scholarly construct. It is not based on material evidence.

[S]cholarship generally dates several other writings or parts of biblical books to this period. From the plethora of the material we will simply look at one (significant) example: the completion of the Jewish law in the form of the Pentateuch, the Torah of Moses, a document of which more than half was written or composed in the post‐monarchial period, i.e. during neo‐Babylonian, Persian, and Hellenistic times. Especially the multiple‐layered literary stratum, commonly called “Priestly Writing”, is best explained in reference to the second temple period. (141)

Here we surely have an enigma. So far we have seen nothing at all in the evidence from the ground that would lead us to suspect anything like the biblical literature being a product of this time and place. On the contrary, what little we do see in epigraphical and the related archaeological evidence bluntly resists any compatibility with the themes of the Pentateuch. One has to imagine the authors of the Pentateuch shutting themselves off from society at large and writing in a way that is contrary to all that exists around them — and then shelving their work until it eventually takes root and is accepted in Hellenistic times.

As Kratz notes, the Pentateuch has the appearance of “multiple-layered literary strata”. When we read of “compromise between several rival groups”, should we necessarily assume this compromise was worked out over centuries?

The literary development has been interpreted as a compromise between several rival groups within Israel . . . (141)

Scholarship seeks an explanation within the Persian period:

. . . a compromise prompted by an initiative of the Persian authorities or as part of the Persian legal practice called imperial authorization. (141)

Again, we are entirely in the realm of unsupported hypothesis:

The historical hypothesis lacks any evidence and cannot be supported by the texts themselves. The literary development is undeniable but it can be shown only in a relative chronology of the literary strata. It is further undeniable that we have Pentateuchal manuscripts amongst the Dead Sea Scrolls, which attest for the period around the middle of the third century BCE several different versions of the texts, including the proto-Samaritan version. To this evidence we have to add the Septuagint that attests the dissemination of the Pentateuch amongst the Greek‐speaking Jews in Alexandria, and Ben Sira, who canvasses the biblical tradition around 200 BCE in Judah. . . . It is equally unclear in which circles these documents were copied, studied, and adhered to and what status the Torah had in Samaria (Mt. Gerizim), Judah (Jerusalem), and Alexandria during the Persian and early Hellenistic period. (141)

So it all comes down to speculation.

We have to admit that we know far less about the history and status of the Pentateuch as Torah during the Persian period than we would like to and we are forced to rely on speculation. The Maccabean revolt during the reign of Antiochus IV during the middle of the second century BCE may provide a historical starting point. Here the Torah is no longer a document of marginalized groups such as the religious community from Qumran but has started to play a significant role in the quarrel over political and economic influence between rival groups within Judaism. During the reign of the Hasmoneans it became (for the first time?) a political and legally binding document for entire Judaism. This is, however, a different story for which we would have to assess the sources for the Hellenistic period. (141f)

Why not assess the sources for the Hellenistic period?

Sometimes scholarly wheels turn very slowly. Let’s farewell Kratz and say hello to Annette Yoshiko Reed sees a “Near East” that is imbued with a more active cultural role in the Hellenistic era. Reed remarks on how slow certain ideas are sometimes picked up and their worth acknowledged.

Scholars of Biblical Studies have habitually treated Near Eastern “influence” as an emblem of pre-exilic antiquity, while interpreting post-exilic sources in terms of resistance or assimilation to Greco-Roman culture – with divisions of periodization, selections of comparanda, and conventionalized reading-practices thereby naturalizing the notion of the two as mutually exclusive. Due in part to the structurally embedded persistence of old dichotomies like Greek/Near East in the study of antiquity, and “Hellenism”/“Judaism” in research on Second Temple Judaism, studies of Hellenistic-era Jewish sources have tended to neglect Near Eastern comparanda from the Hellenistic period, either treating their Jewish echoes as survivals from the pre-exilic past or dismissing them as akin to the return of the repressed.

Reed laments that calls to change our perspective were made by two scholars (J.J. Collins and J.Z. Smith) way back in 1975!

“We can no longer consider Israelite tradition and Hellenistic syncretism as mutually exclusive alternatives.” What we see, rather, is how “the conquests of Alexander had a profound impact on the eastern civilizations” and how this “impact included an unprecedented circulation of ideas among the various peoples” as well as changes in the “conditions of life” and a resultant “transformation of attitudes.”

Both articles have been widely cited. Puzzlingly, however, their calls for attention to Hellenistic-era Near Eastern comparanda have gone largely unheeded.

(From the Introduction in the ebook edition of Reed’s Demons, Angels, and Writing in Ancient Judaism)

Perhaps the first attention to Hellenistic-era Near Eastern comparanda for the Pentateuch is Russell Gmirkin’s Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch.

Kratz, Reinhard G. “Biblical Sources.” In A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire, edited by Bruno Jacobs and Robert Rollinger, 133–48. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 2021.

Reed, Annette Yoshiko. Demons, Angels and Writing in Ancient Judaism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

My reply:

My reply: