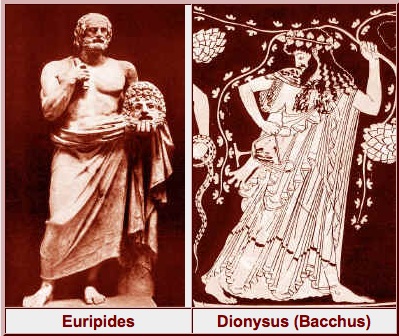

The previous post in this series set out the evidence that there are correspondences between the canonical Acts of the Apostles and Euripides’ famous play Bacchae. This post continues presenting a lay version of classicist John Moles’ article, “Jesus and Dionysus”, published in 2006 in Hermathena. Do the allusions to the Bacchae and the Dionysiac myths and rituals in Acts actually “do” anything? Are they meaningless trappings, perhaps mere coincidences of imagery, or do they open the door to a new dimension of understanding of the work of Acts? If they “do” something meaningful that enhances our appreciation of what we read in a coherent and consistent manner then we have additional evidence that we are seeing something more than accidental correlations with the imagery and themes of the Dionysiac cult.

Anyone who does not know the play Bacchae can read an outline of its narrative in my earlier post linking it to the Gospel of John, based on a book by theologian Mark Stibbe.

We begin with some general points about the practice of imitative writing before addressing the significance of the use of Bacchae in Acts. Where I have added something of my own (not found in John Moles’ discussion, or at least not in the immediate context of the point being made) I have used {curly brackets}.

Why should we expect Luke to have written like this?

This conclusion should not surprise: similar intertextuality marks [Luke’s] engagement with the Septuagint, or, among Classical authors, with Homer. Hence, just as Classical texts are intensely ‘imitative’ in the sense of ‘imitating’ other Classical texts, so too is Acts. (p. 82)

At the end of this post we look at Luke’s literary predecessors who likewise drew upon Bacchae through which to frame their narratives of imperial efforts to impose paganism upon the Jews.

* 2 and 3 Maccabees

** Horace, Epictetus, Lucian

What are the chances of the author of Acts using this Greek play?

Bacchae remained for centuries a popular tragedy: it had been exploited by Jewish writers as a tool through which to explore the relationships between religion and politics, between Judaism and pagan (Dionysus) religion;* and by Stoic and Cynic philosophers** in philosophical and political contexts. The author of Acts (let’s call him Luke) knew of both these groups.

Are we really to expect Luke’s audience would have recognized all of the allusions?

Don’t think, however, that Luke’s knowledge of the way other authors used Bacchae and his own similar use of it in Acts means his audience must have been restricted to a sophisticated elite. Surely he would have expected some of his audience to recognize the allusions — and we know that some of them did* — but that does not mean he must have expected all of them to have done so. We will see that in Acts itself may contain the message that “while Christianity does not need great learning, it can hold its own in that world”: compare the charge against Peter and the original apostles that they were “unlearned” even though they were “turning the world upside down” with the charge leveled at Paul that when he clearly presented much learning to his accusers, that “much learning had made him mad”.

Why would Luke make use of a Greek play in a work of history?

Acts consists of a “highly varied literary texture”. {Pervo’s work demonstrating the characteristics of the Hellenistic novel that are found throughout much of Acts has been discussed on this blog.} Ostensibly the work is a form of historiography, but if so, we can note that in some types of historiography “tragedy” finds a very natural place. Herodotus’s Histories, for example, is one ancient instance of historical writing in which myth is part and parcel of the narrative. {Some scholars have also described it as a prose work of Greek tragedy.} Dennis MacDonald has identified certain Homeric influences in Acts and these Homeric episodes are themselves bound up in motifs and themes of classical tragedy.

How do the Dionysiac parallels highlight key elements in the Acts (and Gospel) narrative(s)?

First, note the key elements that are highlighted by the Dionysiac parallels: Continue reading “The Point of the Dionysiac Myth in Acts of the Apostles, #1″

In my previous post I quoted John Taylor where he referenced chapter 5 of

In my previous post I quoted John Taylor where he referenced chapter 5 of