I have posted several times now on — no I haven’t, sorry, just checked. I thought I have posted on a book by the President of Biblical Archaeology Society of New York, Gary Greenberg, many times now. But a quick check in my blog’s word-search function shows me my memory is deceiving me. So let’s start, like God, at the beginning, in Genesis. I start with the opening chapters (‘myths’) of 101 Myths of the Bible: How Ancient Scribes Invented Biblical History by Gary Greenberg.

I have also posted a few times on reasons some scholars think the Genesis tales are adapted from Plato and Greek philosophy. Is there really a conflict? Was not the Jew Philo also an Egyptian? So with high hopes of an eventual reconciliation I post here Greenberg’s explanations for some of the Bible’s narrative.

Gary Greenberg shows readers that the opening two verses of Genesis point sharply at Egyptian myths of ancient times. The main difference is that the Biblical author wanted to excise Egyptian deities from the old myths and re-write the entire episode as the old Egyptian tale of creation with the Hebrew God replacing the Egyptian actants.

Let’s look, then at Genesis 1:1-2 and compare it with the Egyptian myths.

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit [=”Wind”, ruach] of God moved upon the face of the waters.

Break this down. These verses describe four things:

- an earth and heaven that took up space but had no form or content

- darkness

- a watery deep, within which the unformed space existed; and

- a wind (i.e. “Spirit of God”) hovering upon the face of the waters.

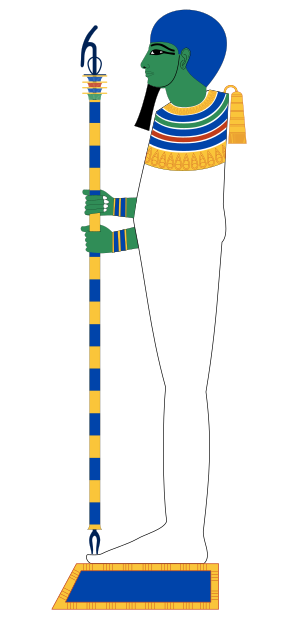

Compare this “Hebrew” scheme of the beginning of the universe with the first four pairs of Egyptian deities and the elements they represented:

- Huh and Hauhet — unformed space, i.e., the shapeless bubble within the deep as described in Genesis as “tohu and bohu”;

- Kuk and kaukut — the darkness on the face of the waters;

- Nun and Naunet — the primeval flood, “the Deep,” the same as the biblical deep; and

- Amen and Amenet — the invisible wind, the biblical “wind” that hovered over the deep.

The Biblical author, wanting to promote ‘monotheism’, removed the personal gods from these images and left readers with nothing but the physical attributes with which those gods had been associated. Additionally, the biblical author removed the Egyptian god’s name from the scene and replaced it with “the wind” alone.

And God Said . . .

The process of biblical Creation begins when God utters a commandment for light to appear. The idea of Creation by command has no counterpart in the Mesopotamian Creation myths. Among the Egyptians, however, Creation by command played a basic role.

The Egyptians believed in the power of the word to create and control the environment, and many Egyptian texts speak about Creation beginning with verbal commands. One describes Amen as “the one who speaks and what should come into being comes into being.” Another text describes Ptah in a similar manner when it says, “Accordingly, he things out and commands what he wishes [to exist],” A reference to the actions of Atum in the creative process tells us “he took Annunciation in his mouth.” (p. 13)

So in the Egyptian myths, after the Theban god Amen (i.e. the wind) initiated Creation, he appeared as the four primary elements (listed above). He then appeared as Ptah, the Creator who created merely by pronouncing a word.

In Egypt the Theban god Amen, representing the wind, was the same deity as the Memphite god, Ptah, the Speaker.

Let there be Light

In Genesis 1 the first thing created was “light” and this is precisely in accord with the Egyptian (and not the Mesopotamian) myths.

So an Egyptian hymn to the god Amen reads (slightly adapted from Greenberg):

The one [Amen] who came into being in the first time when not god was yet created, when you [Amen] opened your eyes to see . . . and everybody became illuminated by means of the glances of your eyes, when the day had not yet come into being.

Compare Genesis 1:4-5

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light Day, and darkness he called Night . . .

Greenberg informs us:

In both the Theban and Memphite Creation myths, after Ptah appears, he commands the appearance of Atum, the Heliopolitan Creator god who first appeared in the form of a flaming serpent , the first light. (p. 14)

Other contingencies beckon me at the moment so I am unable to continue and complete this post as planned. But I will, Ptah willing, return and delineate Greenberg’s views that the entire Genesis Creation account is adapted from Egyptian myths – by means of the personal Egyptian deities simply being replaced with the physical phenomena that they originally represented.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I imagine that this sort of thing is interesting for someone who has rejected the Bible and is looking for another explanation of its origin. Not having read this book I can not make any detailed comments, but there are a number of reasons to reject this type of reasoning. For instance, I hear that Greenberg usually does not cite his sources, so how much of this stuff is taken out of contexts? Even if these quotes are what the Egyptians believed as to the creation of earth and heaven etc., There is still a fatal flaw, how do we know that the Egyptians did not copy and distort the account found in the Hebrew Bible? The only opposing evidence to this is that the Hebrew account can only be dated to the second or third century B.C.E., but lack of evidence is not evidence. I know you will disagree with this reasoning, but the important part of the Bible’s truth is in its meaning. Neil, I would like to ask you a question. Do you know what the main theme of the Bible is about? This theme runs through the entire Bible, from Genesis to Revelation, and it has a very specific purpose, and that is the reason I believe it would be impossible for some ancient farmers to just haphazardly throw it together, or be based on some Hellenistic mythology.

Here is a page about this book, I do not necessarily agree with everything written here.

http://www.tektonics.org/gk/greenbergg01.html

What I find of interest here is the conceptual analogies between Egyptian myths and the Bible. I don’t think it likely that an author was working directly from the Egyptian myths themselves and distilling out the personal deities from what they represented. Rather, these myths were probably part of his thought-world as was Plato and Greek philosophy. The structure of the Genesis myth is more along the lines of Plato’s myths of origins. There is overlap conceptually, however. It’s all part of the stuff, the concepts, the memes, an ancient author might have at hand to work with.

I don’t see any of this as an attack on the Bible, by the way. I like Richard Elliott Friedman’s remarks in his “Who Wrote the Bible?” (since this book comes to hand given our other topic of interest at the moment) — REF addresses those who accuse him of “attacking” the Bible.

I would not quite use the word “awe” myself. But appreciation is surely enhanced by understanding the provenance of what some would say has been the most influential work in our western civilization.

As for the theme of the Bible overall, that is surely a matter of interpretation. But there is nothing miraculous or even extra-ordinary about many books from a common broad theological tradition reflecting common themes. And I know of no-one who argues that “some ancient farmers” haphazardly threw even these together. We are talking about literary elites or our hypothesis makes no sense. And that is where, I believe, the minimalists have the advantage — they have the solid evidence for the provenance of such elites. But I do concur with Thomas L. Thompson’s summary of the common theme found throughout the books of both the Old and New Testaments and that I summed up near the beginning of my recent post: http://vridar.wordpress.com/2012/02/16/where-did-the-bibles-jews-come-from-part-1-hint-where-did-christians-come-from/ I see the Gospel of Mark accordingly being very much an extension of the theological themes of the Second Temple literature. The Book of Revelation presents the same themes with different metaphors. Paul and the other epistle authors explicitly state the same themes themselves.

Well you are right about the interpretation of the Bible. But if we look at it this way, a person does a magic trick in a way that the method is not easily discernible. You can guess at how he did it (interpret) but you will probably be wrong. Some of the facts will not fit. The only sure way of knowing is if the person explains how he did the magic trick, or if you hear it from someone who was told by the original magician. This is an important piece of information, because the Bible was not written directly for everyone, it was written for a select few. Just as the Hebrew portion of the Bible was not written for everyone, it was written for the Jewish people because they were the ones in the covenant with God, no one else was. The same with the New Testament or covenant, it also was written for a relatively small group who would take part in a new covenant that replaced the old covenant with the Jewish people, because they had been rejected by God as a nation for not fulfilling their part of the covenant. And this new covenant does not involve anyone who wishes to be a Christian. It only involves a specific number of people, it is a number that amounts to a certain population of Israel. If we remember that Israel was going to be a nation of kings and priests, and we know that this nation was rejected, a new nation needed to be formed to be those kings and priests. A nation similar in size to Israel. These kings and priest make up the kingdom of God that the NT talks about, and these are the only one who go to heaven to rule with Christ. And these are the only people who can accurately interpret the Bible. The rest of the people who are worthy of a resurrection, remain on earth to live how God intended us to live, and this new earth is governed by this Kingdom of God, made up of those who were in the new covenant. This kingdom was God’s way of bringing the earth back to his original intentions. Which brings us back to Genesis where Adam failed his test and brought sin into the world. When this happened, God brought his plan into action. First he allowed man to rule himself, because that’s what man desired, in hopes that he would see what a terrible job man would do of ruling himself. But at the same time, he provided a promise to all those that would continue to obey him. That promise would culminate with the arrival of God’s son, Jesus Christ (not God himself) and then the Kingdom of God. Jesus has a two part role in this plan. First, he became human and provided that perfect sinless human life and body as a sacrifice to replace Adam’s sinful life, so that he can adopt from Adam, sons and daughters, as many as are willing, and remove their Adamic sin. And finally, this kingdom of God with Jesus as its king will tear down this old system and build a new one during the 1,000 year reign of Christ. Obviously, this is a brief outline and I don’t know if you are familiar with it at all, but if you want to question anything further there is much more information.

On the contrary. It sounds very familiar. It could even be said to have come straight out of the teachings of a church I was once a part of.

I, for one, wouldn’t grant much credence to Gary Greenberg’s assumptions.

He is a criminal lawyer whose pastime is biblical mythology.

His big argument has been exposed in his book: “The Moses Mystery” (Birch Lane Press). His key idea is that Moses was the grand priest of Akhenaten, no less. He left Egypt with his Jewish tribes because of the conflicts following the Pharaoh’s death and the abolition of the cult of Aten and the return to traditional gods , Amun-Ra and his pantheon.

It is highly fashionable to see Akhenaten as the first promoter of monotheism, since he decided to reform the Egyptian priestly class by imposing a new global god, Aten, essentially the sun-god source of all life, energy and drive to replace the multitude of local and national gods.

On another hand, most contemporary scholars and archeologists think that the Jews did not originate in Egypt, never spent any time there, and the whole story of the Exodus is a foundation myth. The story is another product of the formidable myth-making propensity of the Ancient Jews. It is a wonderful idea to have Moses start at the very top of the Egypt priestly establishment.

There was in those times no hieroglyph text offering a compendium of Egyptian religion. The gods were spread all over the country, the texts were mostly inscriptions on monuments, hundreds, thousands of them, that no traveler could have ever visited or viewed. Especially the top priest of the Aten cult would have no obligation to accumulate a knowledge of the multiplicity of god stories illustrated in obscure hieroglyphs all over the country.

Now, of course, Greenberg can use the key college textbooks for Egyptology 101, and extract whatever comparable gods he feels like using.

Using those English quotations as if they had been produced by the Egyptians is an illusion. The English quotes were all manufactured by professional Egyptologists trying to guess the enigmatic meaning of hieroglyphs.

Many groupings can be “translated” (i.e. paraphrased) in many ways, and it is customary to indicate the name of the translator when quoting an important text.

Greenberg borrows his quotations from textbooks that rely on past interpretations and which could be considered, if not dated, at least subject to verification with the most modern readings. Which is not easy, as all this stuff is in expensive scholarly journals that never find their way in the hands of amateurs.

All the abstract words used in English (or ancient Greek) such as “creation”, “time,” “piety,” didn’t exist either in ancient Egyptian. They are all inventions of Egyptologists trying to extract a meaning from the sets of hieroglyphs they are using.

Simply consider some of the simplest hieroglyphs, the “throw-stick” or the “hill-country”, to realize that the correspondence between an Egyptian text and its English translation is extremely elastic and flexible. There’s a lot of subjective guessing that comes into play.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Throw_stick_(hieroglyph)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hill-country_(hieroglyph)

If you established a comparative list of Creation myths among the various stories found in Ancient times, it might be possible to identify a list of shared features, that may be considered an archetypal list, and discover that any two different creation myths offer a lot of parallels.

I was not impressed by the lack of sourcing of Greenberg’s quotes, all borrowed from his basic bibliography, that includes the basic texts used by beginners in this field. Which are the following:

Plutarch Isis & Osiris (Loeb Classical, Moralia, v.5)

The Literature of Ancient Egypt (Yale Un.), ed. Wm Kelly Simpson

Ancient Egyptian Literature (Un. Cal.), by Miriam Lichtheim

Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford), by Sir Alan Gardiner, 1961, a classic

A History of Ancient Egypt (Blackwell), by Nicolas Grimal, 1994

Sumer and the Sumerians (Cambridge), by Harriet Crawford

Babylon (Thames & Hudson), by Joan Oates

Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia & the Ancient Near East (Facts on File), by Michael Roaf

The Sea Peoples: Warriors of the Ancient Mediterranean (Thames & Hudson), by N. K. Sandars

The Secret of the Hittites (Shocken Books), by C. W. Ceram

Ugarit and the Old Testament (Erdmans), by Peter C.Craigie

The Phoenicians: The Purple Empire of the Ancient World (Wm Morrow), by Gerhard Herm

Cambridge Ancient History

I have removed a comment by a “Roger Moor” from here because I felt uncomfortable with the tone in which it spoke of Jews.

Because the Egyptian account was made long before the Hebrew one … You would simply ask yourself which account was older..