| Genesis 10, the “Table of Nations”, describes the post-flood division of the earth among (as traditionally acknowledged) 70 nations.

Compare Deuteronomy 32:8-9 that in its original wording (as established in part by reference to the Dead Sea Scrolls) says Yahweh (YHWH) was one of a host of lesser gods who was assigned a particular nation to possess:

When the Most High apportioned the nations, when he divided humankind, he fixed the boundaries of the peoples according to the number of the sons of God; The Lord’s (Yahweh’s) own portion was his people, Jacob his allotted share.

The number of 70 nations may have derived from a Canaanite tradition that said the consort of the “most high god” (El) had 70 children.

At Ugarit we read in the Baal myth of ‘the seventy sons of Asherah (Athirat)’ (šb’m. bn. ‘atrt, KTU2 1.4.VI.46). Since Asherah was El’s consort, this therefore implies that El’s sons were seventy in number. (Day, 23)

Each nation acknowledged its own god(s):

Babylon (Bel-Marduk, Nebo, Tammuz), Mizraim or Egypt (the Queen of Heaven), the Canaanites (Baal and Asherah), the Arameans (Hadad) and Sidon (Ashtoreth). Later in Genesis we encounter other nations whose gods appear in later biblical books: the Philistines (Dagon), Moab (Chemosh) and Ammon (Molech or Milcom). (Gmirkin, 231)

|

Recall that Plato portrayed the primeval world as various localities divided up among the gods, the gods ruling the people assigned to them (or those they created) in their respective regions.

Also — though Gmirkin does not refer to the event in this chapter (he had raised it in another context earlier) — compare the division of the cosmos among three divine brothers.

There are three of us Brothers, all Sons of Cronos and Rhea: Zeus, myself [Poseidon], and Hades the King of the Dead. Each of us was given his own domain when the world was divided into three parts. We cast lots, . . . (Homer, Iliad, 15. …) see below for a discussion of the relevance to Genesis.

I add these other possible links to Greek myth here to reinforce the case for the Hellenistic sources for the Bible. Gmirkin’s work, as the title itself makes clear, is primarily addressing the case for Plato’s Timaeus and its companion composition Critias lying behind Genesis 2-11.

|

| Given the monotheism of the Bible, we expect to read that all founders are human.

Gmirkin does not discuss in this volume other studies that suggest the mythical origins behind the biblical account of Noah cursing Canaan, son of his youngest son, for “seeing” him naked when he was drunk:

Noah’s interactions with his sons, and how their offspring are thought to become progenitors for all humankind, may be based upon myths in which the main characters were originally gods, an instance of Euhemerism. Like Euhemerus, Israelite authors could interpret the gods acting in the primeval myths of other cultures as really having been “illustrious humans, later idealized and worshiped as gods.” (Louden, 87f)

The Bible itself takes the same road [as the Greek philosopher Euhemerus], as humans replaced the gods of Greek mythology. (Wajdenbaum, 108)

And

While these two mythic types [see adjacent column] are extant in several different traditions, the versions in Genesis 9, though highly truncated, not only seem closest to the forms the same two mythic types assume in Greek myth but also correspond in four particulars absent from the other known versions:

-

-

- the corresponding names, Iapetos/Japheth;

- the altered sequence given of the punished sons;

- the connection with the eponymic Ion/Javan;

- and the closely corresponding wordplays (yapt/Yepet, Τιτήνας/τιταίvoντας). (Louden, 87f – my formatting)

|

Great Ouranos [=Heaven] came, bringing on night, and upon Gaia =Earth] he lay, wanting love and fully extended; his son, [=Cronos] from ambush, reached out with his left hand and with his right hand took the huge sickle, long with jagged teeth, and quickly severed his own father’s genitals (Hesiod, Theogony, 176ff]

Plato thought that such a scandalous story should be censored. . . (Plato, Rep. 377 b). It seems likely that the biblical writer recycled that story but modified the detail of Cronos castrating his father into Ham seeing his father naked; it is most noteworthy that some Jewish midrashim interpret Ham’s deed as an actual castration. . . . (Wajdenbaum, 108)

Now behind Genesis there seems to lie a story in which Noah’s sons did more than see him naked: Gen 9:24 “When Noah awoke from his wine and knew what his young son had done to him …” What can this have been but castrating him? The association of Iapetus with Kronos, and hence with the castration of Ouranos, suggests that he is the same figure as Japheth youngest son of Noah. (Brown, cited by Louden, 87)

And

I suggest, then, that to connect the Flood myth with stories set in subsequent eras, Israelite tradition utilized a combination of two common types of myth set in primeval times: one in which intergenerational conflict among gods resulted in a son taking power by castrating his father, the former king of the gods; and another in which three brother gods draw lots to determine their own portions of rule and to establish hierarchical relations between themselves. (Louden, 87)

See also What Did Ham Do to Noah? |

|

Genesis 10:1-32

Now these are the generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth: and unto them were sons born after the flood.

The sons of Japheth; Gomer, and Magog, and Madai, and Javan, and Tubal, and Meshech, and Tiras. And the sons of Gomer; Ashkenaz, and Riphath, and Togarmah. And the sons of Javan; Elishah, and Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim. By these were the isles of the Gentiles divided in their lands; every one after his tongue, after their families, in their nations.

6 And the sons of Ham; Cush, and Mizraim, and Phut, and Canaan. And the sons of Cush; Seba, and Havilah, and Sabtah, and Raamah, and Sabtechah: and the sons of Raamah; Sheba, and Dedan. . . . And Mizraim begat Ludim, and Anamim, and Lehabim, and Naphtuhim, And Pathrusim, and Casluhim, (out of whom came Philistim,) and Caphtorim. And Canaan begat Sidon his first born, and Heth, And the Jebusite, and the Amorite, and the Girgasite, And the Hivite, and the Arkite, and the Sinite, And the Arvadite, and the Zemarite, and the Hamathite: and afterward were the families of the Canaanites spread abroad.

19 And the border of the Canaanites was from Sidon, as thou comest to Gerar, unto Gaza; as thou goest, unto Sodom, and Gomorrah, and Admah, and Zeboim, even unto Lasha.

20 These are the sons of Ham, after their families, after their tongues, in their countries, and in their nations.

21 Unto Shem also, the father of all the children of Eber, the brother of Japheth the elder, even to him were children born. The children of Shem; Elam, and Asshur, and Arphaxad, and Lud, and Aram. And the children of Aram; Uz, and Hul, and Gether, and Mash. And Arphaxad begat Salah; and Salah begat Eber. And unto Eber were born two sons: the name of one was Peleg; for in his days was the earth divided; and his brother’s name was Joktan. And Joktan begat Almodad, and Sheleph, and Hazarmaveth, and Jerah, And Hadoram, and Uzal, and Diklah, And Obal, and Abimael, and Sheba, And Ophir, and Havilah, and Jobab: all these were the sons of Joktan.

30 And their dwelling was from Mesha, as thou goest unto Sephar a mount of the east.

31 These are the sons of Shem, after their families, after their tongues, in their lands, after their nations.

32 These are the families of the sons of Noah, after their generations, in their nations: and by these were the nations divided in the earth after the flood.

|

While it is now widely acknowledged that the genealogical structure of Genesis, and especially the division of nations in Genesis 10, is broadly indebted to Greek antecedents . . . a specific indebtedness to Critias and Timaeus has generally escaped consideration. (Gmirkin, p. 232)

Critias 113e-114c

By copying this section of Critias below I do not intend it to be read as a direct hypotext for Genesis 10. Rather, what one finds in common with Genesis 10 is the cogently brief account covering the description of how an entire land was divided up, with geographic markers for verisimilitude, with geographic names taken from founding figures, and other details you may discern for yourself:

[Poseidon] fathered and reared five pairs of twin sons. Then he divided the island of Atlantis into ten parts.

He gave the firstborn of the eldest twins his mother’s home and the plot of land around it, which was larger and more fertile than anywhere else, and made him king of all his brothers, while giving each of the others many subjects and plenty of land to rule over.

He named all his sons. To the eldest, the king, he gave the name from which the names of the whole island and of the ocean are derived — that is, the ocean was called the Atlantic because the name of the first king was Atlas.

To his twin, the one who was born next, who was assigned the edge of the island which is closest to the Pillars of Heracles and faces the land which is now called the territory of Gadeira after him, he gave a name which in Greek would be Eumelus, though in the local language it was Gadeirus, and so this must be the origin of the name of Gadeira.

He called the next pair of twins Ampheres and Evaemon;

he named the elder of the third pair Mneseus and the younger one Autochthon;

of the fourth pair, the eldest was called Elasippus and the younger one Mestor;

in the case of the fifth pair, he called the firstborn Azaes and the second-born Diaprepes.

So all his sons and their descendants lived there for many generations, and in addition to ruling over numerous other islands in the ocean, they also, as I said before, governed all the land this side of the Pillars of Heracles up to Egypt and Etruria.

|

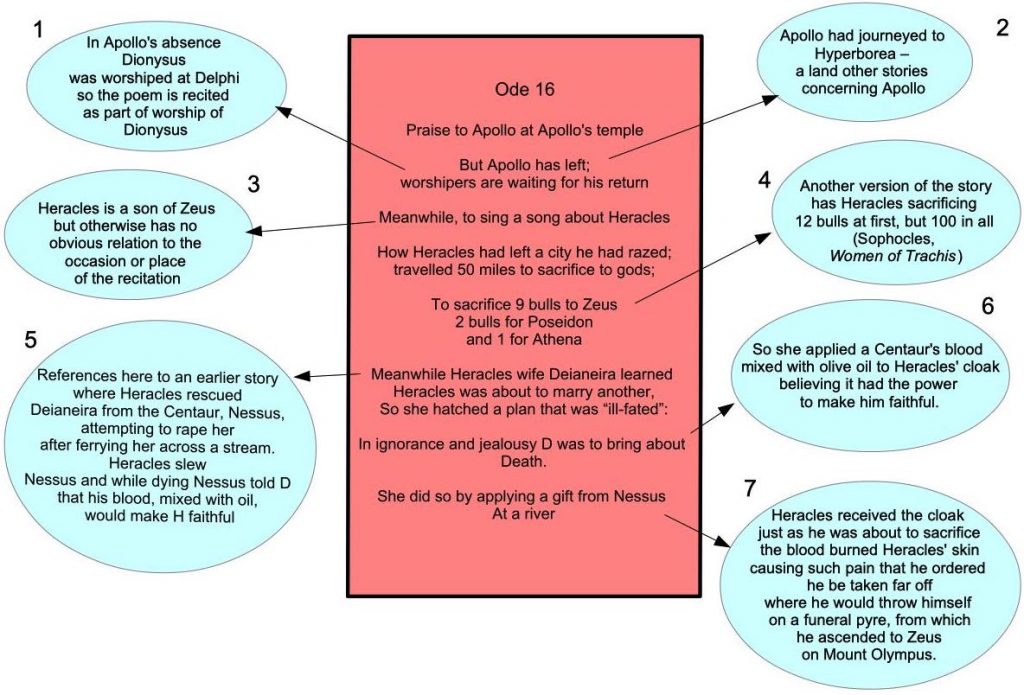

| I omitted a section in the above chapter. The reason, again, is to cast an eye beyond what Gmirkin discusses and to note other Greek influence. Here we have a vignette breaking into a genealogy that reminds us of a famous Greek poetic genealogy of heroes who were born from gods.

The genealogies of the Old Testament, especially the Book of Genesis, are much more closely comparable to the Hesiodic ones [than to Mesopotamian lists], both in their multilinearity and in their national and international scope. (West, 13)

8 And Cush begat Nimrod: he began to be a mighty one in the earth. He was a mighty hunter before the Lord: wherefore it is said, Even as Nimrod the mighty hunter before the Lord. And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar. Out of that land went forth Asshur, and builded Nineveh, and the city Rehoboth, and Calah, And Resen between Nineveh and Calah: the same is a great city.

|

The [Greek] genealogies are not homogeneous. They contain folktale, fiction, and saga in very varying proportions. These variations reflect the different sorts of material that were available in different regions for the construction of genealogies. (West, 137)

Fragments from Hesiod’s genealogy of founding Greek heroes:

Of mortals who would have dared to fight him with the spear and charge against him, save only Heracles, the great-hearted offspring of Alcaeus? Such an one was strong Meleager loved of Ares [= the god of war], the golden-haired, dear son of Oeneus and Althaea. From his fierce eyes there shone forth portentous fire: and once in high Calydon he slew the destroying beast, the fierce wild boar with gleaming tusks. In war and in dread strife no man of the heroes dared to face him and to approach and fight with him when he appeared in the forefront. But he was slain by the hands and arrows of Apollo, while he was fighting with the Curetes for pleasant Calydon. (fr 98 )

Aloiadae. Hesiod said that they were sons of Aloeus, — called so after him, — and of Iphimedea, but in reality sons of Poseidon and Iphimedea, and that Alus a city of Aetolia was founded by their father. (fr6 )

|