Broken links fixed — 25th November 2009

The Infancy Narratives of Luke, the first 2 chapters of this gospel, are well integrated into the larger narrative of the rest of Luke and Acts (Tannehill). But that does not preclude the possibility that they were added later to an original Luke, with the final redactor reworking that original gospel to thematically and theologically so that it formed a new whole, a new single work which included new material and added the Book of Acts as a second part to the narrative. Tyson fully embraces the narrative and thematic unity between the Infancy Narratives and the rest of the canonical form of the gospel, but he also sees reasons for believing that these opening chapters (along with other material and the Book of Acts) were added to a pre-canonical form of Luke in order to undermine the gospel of Marcion. Marcion’s gospel, he argues, was based on an “original Luke”. First Marcion edited this “original”, and then the canonical redactor did likewise, adding the first two chapters that we know today, in order to turn it into an anti-Marcionite document.

Tyson’s reasons (with reference to Streeter, Fitzmeyer, Raymond Brown, Cadbury, Conzelmann, Vincent Taylor, Knox, and his own earlier work on the Judaistic unity of the gospel), for believing that the Infancy Narratives of Luke were a later addition to the “original Luke” (which was also redacted) are summarized here:

Luke 3:1 is still an excellent beginning for a Gospel

- Luke 3:1-2 is a most suitable beginning. It is more precise in its chronological and geographical setting than Luke 1:5. Luke 3:1-2 places the drama on a world stage, without neglecting the parochial details. Carefully composed time setting details makes for an appropriate beginning of an historical or biographical account.

- Luke 1:5-2:52 appears to stand apart from everything else in the gospel.

- If Luke used Mark as a source it is not unlikely that he also began his gospel where Mark did.

- The genealogy in Luke 3:23-38 is appropriate only if Luke 3:1 is the beginning of the gospel. The genealogy only works (makes Jesus a son of David) if Joseph is his father, which conflicts with the birth narrative .

- John the Baptist is introduced in 3:1-2 as if for the first time.

- Requirements for apostleship in Acts 1:22 appear to designate the beginning of the gospel as the baptism of Jesus.

- Marcion’s gospel also began with the reference to the 15th year of Tiberius, although not to introduce John the Baptist but to designate the first earthly appearance of Jesus who came down to Capernaum (Luke 4:31).

Contrasts of narrative tone

- There is a profound sense that something new has begun at Luke 3:1. Luke 3:1 marks an abrupt change of time (from Herod to Tiberius) and marks a silent interval of some 18 years.

- Contrasting tones, including a contrast between infancy and adulthood, between miraculous births and wilderness preaching, between prophetic blessings and demonic temptations, between a time of good will and imprisonment.

- There is a sense of “abrupt change from a comfortable, idyllic, semimythical world to the cold cruel world of political social reality.” (p.94)

Different treatment of prominent characters

John the Baptist

Although there is some continuity between the treatment of John the Baptist in the Infancy Narrative and the remainder of the gospel (in both parts John is the preparer of the way for Jesus), there are also discontinuities.

There is a distinct contrast between the closeness of John the Baptist and Jesus in 1:5-2:52 and the distancing of these two in rest of gospel. This is in stark contrast to the first 2 chapters where the author has closely knit a narrative comparing the likenesses and differences between the two in a step by step sequence.

- Luke 16:16 can be read as assigning John to the age of Israel, and thus separated from age of Jesus.

- John and Jesus occupy different geographic areas after the Infancy Narratives.

- John completes his mission before the baptism of Jesus.

- John is imprisoned before Jesus begins his ministry.

- John does not even baptize Jesus in the main body of the gospel. The emphasis is on the descent of the Holy Spirit and the voice from heaven, not the baptism of Jesus.

The Parents and Family of Jesus

- Joseph is mentioned five times in the Infancy Narratives but only twice thereafter.

- Mary is a lead character in the opening chapters. She is mentioned sixteen times in the Infancy Narratives but only once afterwards. In the early chapters she is treated with near veneration: she is given a great promise by the archangel Gabriel, and then the focus of Simeon’s dramatic prophecy, but then simply disappears except for one strange mention where Jesus rejects her in favour of his disciples.

- In that later mention the brothers of Jesus are also mentioned, which is again strange given there was no hint beforehand that they existed.

- The opening two chapters portray a very positive relationship between Jesus and his family, and a very positive picture of Jesus’ family itself. This contrasts sharply with the negative and rejectionist view of families in the remainder of the gospel. There, Jesus says he has come to create family division (12:53), that his disciples must hate their parents to follow him (14:26). Nor does this gospel, unlike those of Mark and Matthew, condemn the custom of Corban which allowed parents to be neglected if one made an offering to the Temple.

- The genealogy does not work given the Infancy Narrative opening of the gospel. The Infancy Narratives demand that the birth of Jesus be more miraculous than that of John. So to this end the focus has to be on Mary there more than Joseph. This early narrative also stresses Jesus being the Son of David. But later in the main body of the gospel the genealogy traces Jesus’ ancestry through Joseph. So the genealogy does not cohere with the Infancy Narrative and its portrayal of Jesus being the Son of David by Mary.

Linquistic Style Differences

- The Septuagintal style (and content) is found throughout Luke-Acts but is most prominent in the Infancy Narratives.

- Also the heavy Semitic flavour in the Infancy Narratives can be found throughout Luke-Acts, but is most pronounced in the first 2 chapters.

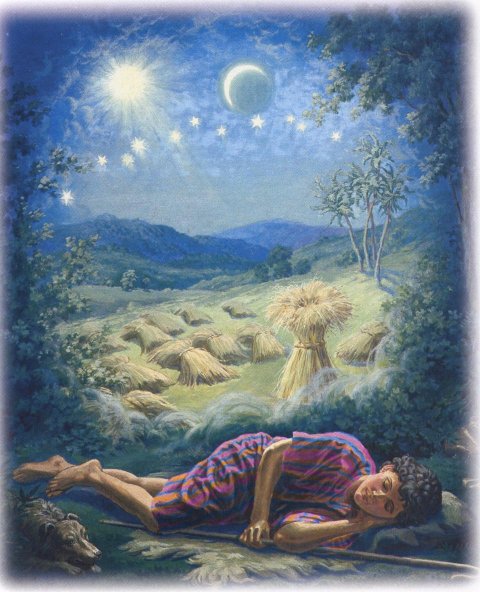

- The style of the Infancy Narratives serves to link Jesus to the Hebrew Scriptures. It transports the reader back to world of the ancient Hebrew writers and prophets.

- The characters’ lives are set against this background and governed by the values of the Hebrew Scriptures. The description of piety of the characters is idyllic.

Differences in Ideology

- The different ideologies of the family expressed in the Infancy Narratives and the body of the gospel has been discussed above.

- The treatment of Jews and Judaism in the Infancy Narratives is strikingly positive in contrast with rest of Luke-Acts.

- Chapters 1-2 function to connect Jesus and the Baptist to the world of the Hebrew prophets and ongoing Jewish piety and expectations. The tone is almost entirely one of hope and optimism.

The appropriateness of all the above as a reaction against Marcionism

- These opening chapters take the reader back 30 years before Jesus began his ministry, back to the reigns of Herod the Great and Caesar Augustus, as if to deny the Marcionite claim that Jesus’ first appearance was in the time of Tiberius (Luke 3:1).

- The Infancy Narratives emphasize that Jesus was born of a woman. He did not, as per Marcion, suddenly descend from heaven to Capernaum. For Marcion, a human birth for Jesus would have been degrading.

- Gabriel’s message seems chosen to offend Marcionites for its anatomical detail: to conceive in her womb, produce a son, leaping in her womb.

- Jesus is repeatedly called a baby or a child — as also is John.

- The language throughout emphasizes Jesus’ humanity, and proximity to family, and his similarities with John.

- Close relationship with John is conveyed through angelic announcements predicting their conception and births, the narratives about their births, their naming, the circumcision of both, the similar summary statements conclude narratives of both. Compare the author of Acts drawing similar narrative parallel units for the reader to compare Peter and Paul.

- The Infancy Narratives stress the relationship of Jesus to Israel, the prophetic anticipation of his coming, of Jesus being the fulfilment of Jewish expectation.

- The same chapters stress the relationship of Jesus to the Jewish people. He is of the House of David; David is Jesus’ father; he is born in City of David.

- The family of Jesus is faithful to Jewish practices — note the stories of the presentation of Jesus and Mary’s purification. They are pious Jews, observing Torah, supporting the Jerusalem Temple, practicing sacrifices, observing Jewish festivals.

- And Jesus incorporated these practices, being obedient to parents.

- Jesus’ Jewishness is especially stressed in the story of his circumcision. This vitally links him with Judaism. and would have been especially offensive to Marcionites.

- Pervasive influence of the Hebrew Scriptures is especially pronounced in the Infancy Narratives, in language, tone and content.

- Prominent use of Daniel and Malachi (Malachi is drawn on in the announcement of the birth of John; and in the appearances of Jesus in the Temple)

- Eight characters from the Hebrew bible are mentioned in the Infancy Narratives: Aaron, Abijah, Abraham, Asher, David, Elijah, Jacob, Moses.

- There are also references to the holy prophets predicting Jesus. (Marcion denied that Jesus was the fulfilment of the prophetic scriptures. He interpreted these literally, not allegorically, to refer to a conquering Messiah.)

- Quotations, allusions and models of narratives are closely based on the Septuagint Hebrew Scriptures (e.g. the presentation of Samuel was probably the model for the story of Jesus’ presentation at the Temple).

Tyson writes:

These considerations make it highly probable, in my judgment, that the Lukan birth narratives were added in reaction to the challenges of Marcionite Christianity.

If these two chapters were a part of the original Luke, it is very hard to understand why Marcion would have chosen such a gospel with such highly offensive chapters to edit to begin with. On the other hand,

it would be difficult to imagine a more directly anti-Marcionite narrative than what we have in Luke 1 :5- 2:52. (p.100)

Next — the postresurrection accounts (and the Preface) of Luke . . . .