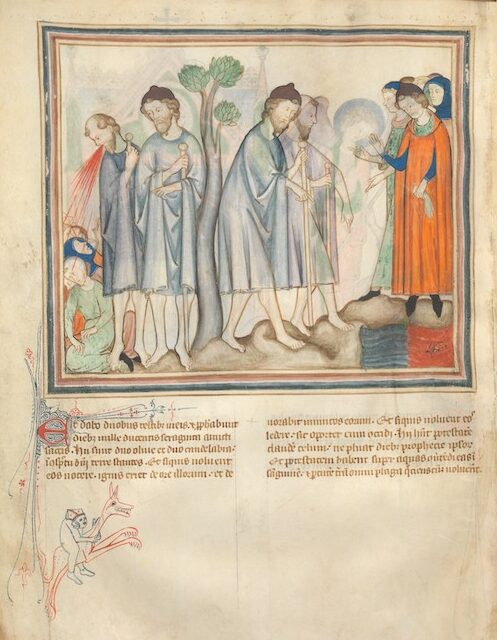

The above identification of the two witnesses draws upon the imagery in Zechariah 4:

1 And the angel who talked with me came again and waked me, as a man who is wakened out of his sleep,

2 and said unto me, “What seest thou?” And I said, “I have looked and behold, a candlestick all of gold with a bowl upon the top of it, and his seven lamps thereon, and seven pipes to the seven lamps which are upon the top thereof;

3 and two olive trees by it, one upon the right side of the bowl, and the other upon the left side thereof.”

4 So I answered and spoke to the angel who talked with me, saying, “What are these, my lord?”

5 Then the angel who talked with me answered and said unto me, “Knowest thou not what these be?” And I said, “No, my lord.”

6 Then he answered and spoke unto me, saying, “This is the word of the Lord unto Zerubbabel, saying, ‘Not by might nor by power, but by My Spirit,’ saith the Lord of hosts.

7 Who art thou, O great mountain? Before Zerubbabel thou shalt become a plain; and he shall bring forth the headstone thereof with shoutings, crying, ‘Grace, grace unto it!’”

8 Moreover the word of the Lord came unto me, saying,

9 “The hands of Zerubbabel have laid the foundation of this house; his hands shall also finish it. And thou shalt know that the Lord of hosts hath sent me unto you.

10 For who hath despised the day of small things? For they shall rejoice and shall see the plummet in the hand of Zerubbabel with those seven. They are the eyes of the Lord, which run to and fro through the whole earth.”

11 Then answered I and said unto him, “What are these two olive trees upon the right side of the candlestick and upon the left side thereof?”

12 And I answered again and said unto him, “What be these two olive branches, which through the two golden pipes empty the golden oil out of themselves?”

13 And he answered me and said, “Knowest thou not what these be?” And I said, “No, my lord.”

14 Then said he, “These are the two anointed ones, who stand by the Lord of the whole earth.”

The two anointed ones in Zechariah are the political leader, Zerubbabel, and the high priest, Joshua.

Thomas Witulski addresses the various interpretations of the two olive trees and two candlesticks in Revelation that are found in the commentaries and concludes that the author meant to depict two historical persons (as opposed, for example, to representatives of Christianity), but that he also did not want them to be understood as spiritual heirs of Zerubbabel and Joshua.

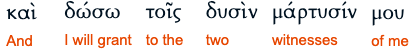

Zerubbabel and Joshua were symbolized by two branches of the olive tree and were not represented in any way by the candlestick. The two witnesses [μάρτυσίν], in contrast, were symbolized by both two candlesticks and two olive trees (not branches). In Zechariah, there is a clear distinction between the candlestick and the olive trees but in Revelation 11 the two images are united as the two μάρτυσίν.

Of particular significance is that Revelation notably avoids using the title of “anointed ones” that is assigned to Zerubbabel and Joshua. Even though in Revelation we read a partial quotation of Zechariah 4:14, we see that the two μάρτυσίν are not allowed a title of special anointing. For Christians, after all, there was only one anointed one, Jesus Christ. The two μάρτυσίν have no such spiritual title. Further, from what we know of early Christianity, it is unlikely that outstanding status would have been given to any members since in a sense all Christians were “priests and kings”, and there were many prophets among them.

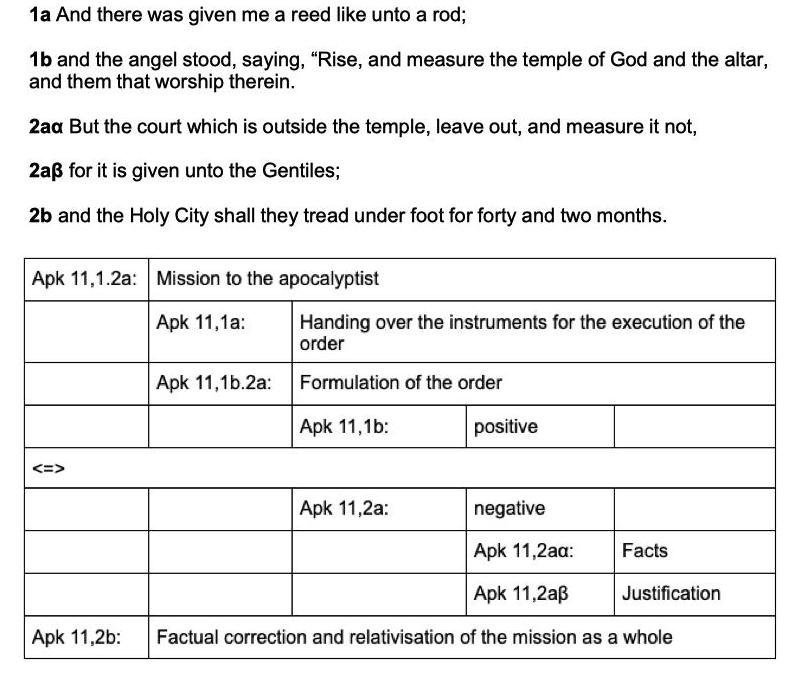

Nor does the apocalyptist of Revelation link the two μάρτυσίν with plans to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem. One might have expected such an association given that Revelation 11 begins with a commission to measure a temple and Zechariah has a strong focus on the role of Zerubbabel and Joshua in the building of the second temple.

So why does Revelation cast the two μάρτυσίν as two olive trees and two candlesticks if they are not “anointed ones” and are not engaged in a rebuilding of the temple — and, as we saw in the previous post (part A), are apparently commissioned by a heavenly being of a lesser status than the one commissioning the author John? Witulski’s view is that the author of Revelation was working very freely with a prophetic tradition based on Zechariah where the two leaders of Israel, the political and priestly heads, were represented by two candlesticks and two olive trees.

Moses and Elijah?

The powers attributed to the two μάρτυσίν bring to mind the miracles of Moses and Elijah. However, both of the μάρτυσίν are said to wield these powers so it is unlikely that they are meant to represent the two OT heroes. Elsewhere in both the OT and Jewish writings some of these powers are described quite independently of associations with Moses and Elijah (e.g. 1 Kings 8:35; 1 Sam 4:8).

Confrontation with political enemies

Continue reading “The Two Witnesses of Revelation 11 – part B”