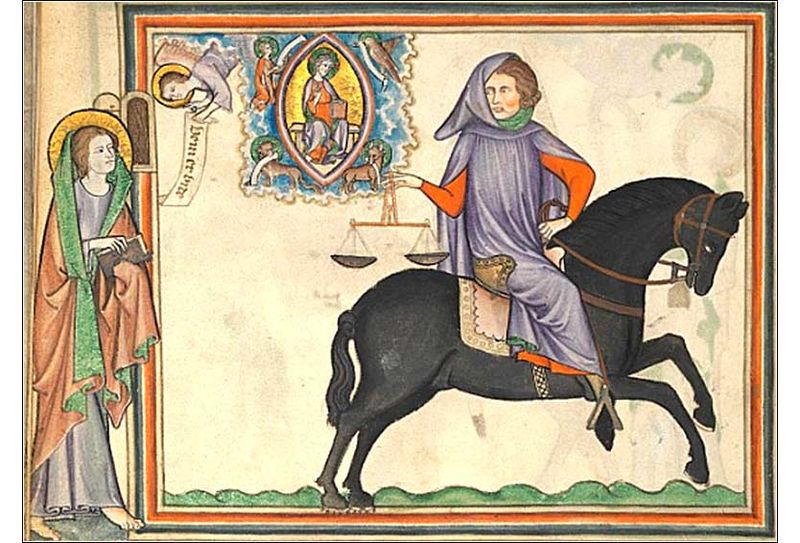

And when He had opened the third seal, I heard the third living being say, “Come and see!” And I beheld, and lo, a black horse; and he that sat on him had a pair of balances in his hand.

And I heard something like a voice from among the four living creatures saying, “A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny; and see thou hurt not the oil and the wine!” — Revelation 6:5-6

A pair of balances in his hand

Many commentators interpret the image of scales and the weighing of grain as a representation of famine that often follows in the destruction of croplands during a time of warfare. Two Old Testament verses are commonly referenced:

Leviticus 26:26 When I afflict you with famine of bread, then ten women shall bake your loaves in one oven, and they shall render your loaves by weight; and ye shall eat, and not be satisfied. (LXX)

Ezekiel 4:16-17 And he said to me, Son of man, behold, I break the support of bread in Jerusalem: and they shall eat bread by weight and in want; and shall drink water by measure, and in a state of ruin: that they may want bread and water; and a man and his brother shall be brought to ruin, and they shall pine away in their iniquities. (LXX)

Thomas Witulski (whose arguments for a Hadrianic date for the book of Revelation I have been outlining) identifies the following problems with attempting to link those verses in Leviticus and Ezekiel with the third horseman of the apocalypse:

— the term for “scales” or “balances” does not appear in either Lev 26 or Ez 4;

— Lev 26 and Ez 4 speak of “bread” but “bread” is not the subject of Revelation 6:5-6;

— the scales are used to measure by weight, but what follows is not a weight measure but a volume measure; the scales are therefore not directly related to what follows – and in the words of Aune (Rev 6-16, 396), “the presence of the scales is not illuminated by what follows”;

— as we saw in the vision of the first horseman, the bow is mentioned without the accompanying reference to arrows, thus suggesting that the bow was introduced as a symbol rather than a weapon to be used, so here, scales are mentioned without the expected accompanying reference to weights. It follows that the scales, like the sword, are a symbol rather than a tool for use;

— no Old Testament reference to scales speaks of them being held in one hand as we find in Revelation 6:5.

The image of scales being held in hand appears frequently in Roman imperial coinage from the later part of the first century and throughout the second. The goddess Aequitas represents equal justice, equal decisions made in comparable cases, and stands for Roman jurisprudence in general or more specifically to the person entrusted to administer justice.

Something like a voice in the midst of the living creatures

W rejects the common interpretation that the voice is God’s. Whenever the seer wants to inform readers that God is speaking he does so unambiguously (e.g. Revelation 21:3 where the voice is noted as coming from God’s throne and hence from God). Rather, part of the vision of the rider of the black horse is “something like a voice” heard coming from the four living creatures and addressed directly to the rider (6:6). He is to carry out a command.

A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny

High prices indicate scarcity but this is not a scarcity that affects the whole earth. The cosmic catastrophes are yet to come: see the side box.

Some scholars have thought that the scarcity amounts to a serious famine and the command not to interfere with the cultivation of olive tree plantations and vineyards is responding to attempts to worsen the effects of the famine or to alleviate it. Against that idea, though, is the fact that land suitable for oil and wine production is not typically suitable for wheat and barley crops, nor are oil and wine reasonable food substitutes for wheat and barley.

Studies of the amounts and prices do indicate that prices are high but not at the levels that suggest a famine:

J. Kobes states that an adult working man needs between 200 and 250 kg of grain per year . . . [and] that women and children got by with one third less grain . . . . But this means – always assuming that the daily wage of a day labourer amounts to one denarius – that on the basis of the grain prices mentioned in Rev 6:6b, a day labourer can secure the livelihood of a family of four with his daily earnings. This means first of all that the shortage of grain implied in Rev 6,6b.c can in no case be interpreted in the sense of a famine. (Witulski, 172f – translation)

and another supporting view:

A measure of wheat, i.e. the daily necessary ration, thus devoured the daily wage of a labourer at that time (cf. Mt 20,2). For the same price, he receives three times the amount of barley, which was used to produce cheaper bread. The inflation does not yet reach the highest level of hardship, but it hits the simple people. (Müller, 168 – translation)

W concludes:

. . . moreover, the calculations carried out above and the resulting but striking correspondence of the daily requirement of grain calculated for a family of four and the amount of grain that can be acquired for the daily wage of a denarius according to Rev 6,6b, suggest that the apocalyptist in Rev 6,6b.c takes up provisions of an – otherwise unknown – decree issued either by the emperor himself or by the administration of the province of Asia within the framework of the general provision for subsistence. In the context of such a decree, the – quite high – prices listed in Rev 6,6b would then represent upper limits for the sale of the scarce grain, which should prevent the prices to be paid for it from shooting up even further, which would have the consequence that especially the poorer strata of the inhabitants of the province of Asia would no longer be able to secure their basic supply of grain. (W. 174 – translation)

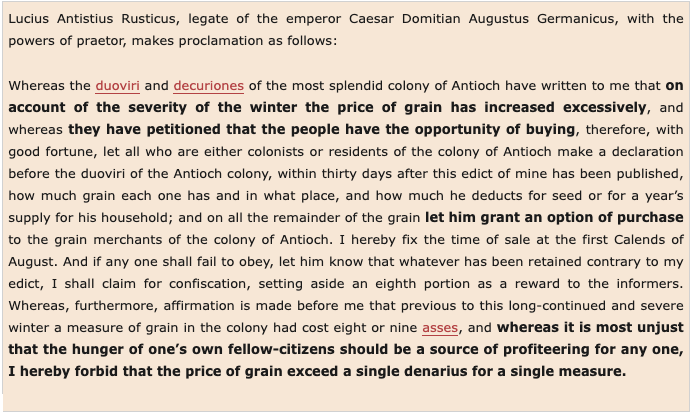

Here is one such edict that has survived the times, one that was originally issued in the region of Galatia in Asia Minor in 92/93 CE.

Note that the edict compels the sale of grain in a time of shortage and sets the upper price limit. Note, further, that the upper price set by “the voice from the four creatures” in the vision of the third seal is far higher than the one set by order of Antistius Rusticus:

This suggests that the emergency situation reflected in Rev 6,6b must have been much more comprehensive and profound than the merely localised one to which Antistius Rusticus reacts with his order. (W. 176 – translation)

Some have attempted to relate Revelation 6:6 to the emperor Domitian’s “Edict on Vineyards”, but the evidence concerning this edict suggests that Domitian’s intention was to protect Italian winegrowers against non-Italian competition. It had nothing obvious to do with grain production.

W concludes,

The figure of the third ‘apocalyptic horseman’ appearing in Rev 6:5b.c.f. obviously points to a person who is concerned with the administration of justice and – apparently as a recipient of orders or as an intermediate link in a chain of orders – is responsible for the sufficient supply of the population with affordable grain in the area of work for which he is responsible. (W. 180)

The third ‘apocalyptic horseman’ – a governor of the Roman province of Asia

W suggests that the third apocalyptic horseman is a person responsible for the administration of justice in the Roman province of Asia at the time of the Jewish uprisings in North Africa. These revolts had led to a breakdown of the imports of grain from Egypt to cities in Asia that had long depended on Egyptian grain.

In order to avoid – if only for reasons of aequitas – prices shooting up to entirely unaffordable heights, the governor capped prices by order of his βασιλεύς and at the same time decreed that lands hitherto designated as oil and wine-growing areas should not be hastily converted into grain-growing areas, a measure possibly considered in the province of Asia or by the governor himself, which, however, for several reasons could have remedied neither the current nor a latent supply crisis. (W. 181)

Müller, Ulrich B. Die Offenbarung des Johannes. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 1995.

Robinson, David M. “A New Latin Economic Edict from Pisidian Antioch.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 55 (1924): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/283004.

Witulski, Thomas. Die Vier Apokalyptischen Reiter Apk 6,1-8: Ein Versuch Ihrer Zeitgeschichtlichen (neu-)interpretation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

2 thoughts on “The Black Horse of the Apocalypse and its Rider”