This post picks up from Measuring the Temple where we set out various interpretations of the first two verses of Revelation 11 (where John is commanded to measure the temple) as they are discussed by Bielefeld University‘s Professor Thomas Witulski in Apk 11 und der Bar Kokhba-Aufstand. Here we do the same for the two witnesses in Rev 11:3-13.

There have been two approaches to the scholarly work on the two witnesses: one search has attempted to find the models from Jewish traditions upon which the two witnesses are based; the other has focussed on identifying the figures “in reality”: are they historical persons who embody ancient prophetic characters, or are they two ancient prophets returned at the moment of crisis, or are they meant to be symbols?

The early Jewish templates

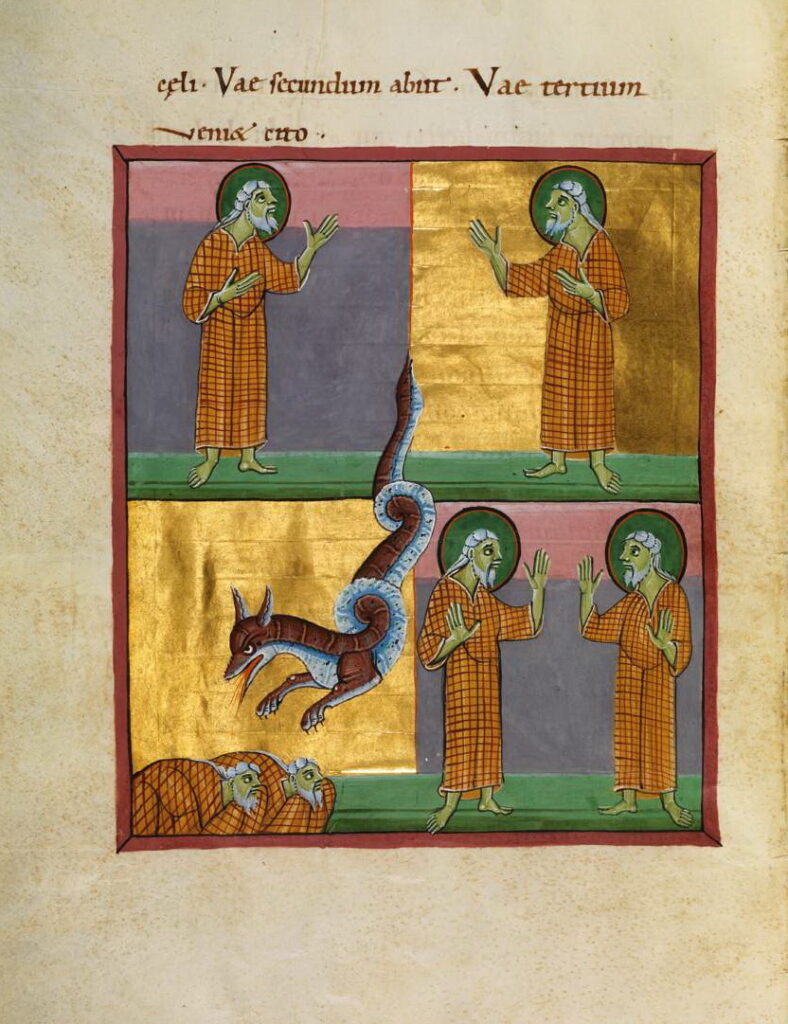

Enoch and Elijah come to mind on the basis that both are said to have ascended to heaven without first dying. There was apparently a widespread belief that one or both of them would return one day to complete the work they had begun before being taken to heaven. One has to wonder how such a model fits Rev 11:6 which reads much more like the works of Moses, though:

and they have power to turn the waters into blood and to strike the earth with every kind of plague . . .

Victorinus of Pettau wrote one of the earliest commentaries on Revelation in which he proposed that the models for the two witnesses were Elijah and Jeremiah. Victorinus relied upon a tradition that Jeremiah, like Elijah, had been translated to heaven without seeing death. W. notes, however, that the same kind of problem applies to Jeremiah: the two witnesses perform the works of Elijah (calling fire down from heaven and proclaiming the end to rainfall for an extended period) and Moses (turning waters to blood and striking the earth with plagues) — none of which can be related to anything we know of Jeremiah.

Since Elijah eliminated his enemies by calling down fire from heaven and punishing Israel with a drought, and Moses turned waters to blood and ordered plague after plague, most exegetes have settled on Elijah and Moses being the templates for the two witnesses. They perform the same miracles, after all. Christian tradition, according to the canonical gospels, further links Elijah and Moses at the time they appeared together at Christ’s transfiguration.

Nonetheless, the notion that Moses had ascended to heaven in the past as Elijah had done is “only very rarely attested in Jewish and Christian tradition, if at all.” (Witulski p. 9 – citing Aune)

Witulski concludes that while it cannot be denied that the author of Revelation used traditional material form Jewish and Christian sources, his interest was not to equate the two witnesses with those traditional figures but only to use traditional motifs to shape a particular profile for them.

Who/What are they?

Are they symbolic figures?

Some exegetes have understood the two witnesses to represent the Old and New Testaments, symbolic of the church witnessing to the power of the Jewish religion that has been “fulfilled” in Christianity, or as representatives of the Old Testament prophetic message alongside the New Testament apostolic witness. Another proposal is that the two witnesses represent the spirit of God and the prophets: compare Rev 19:10 and Rev 22:9.

If so, how can one explain the clearly personal depiction of the couple? They are presented in a way for us to naturally think of them as individual persons. Of course, individual persons can also be representatives of groups: but if that were the case here we would expect some flags or indications in the narrative to help the original readers to see that these persons are indeed representative.

Are the two witnesses representatives of the church? If so, we must explain why the author hid their identity so cryptically. He had no qualms about identifying the seven churches in the opening chapters.

Are they unknown persons who are yet to appear?

Did the author mean for us to not look for them in his own time but to expect the two witnesses to appear in the last days, at the moment of the final act of history?

The problem with that idea is that elsewhere in Revelation the emphasis is on the current stresses facing God’s people. The apocalyptist is constantly admonishing and encouraging readers in his own time to hold fast to their faith despite attacks from Satan’s agents on earth. References to what the world is experiencing “now” fill the book. Should we not therefore expect the two witnesses to be part of that contemporary setting?

Are they identifiable historical figures known to the author and first readers?

Two candidates are the apostles James and John, the sons of Zebedee (Bacon, 1927). The gospels of Mark and Matthew indicate that these two were to be martyred before the fall of Jerusalem:

Jesus said to them, You will indeed drink from my cup . . . Mark 10:39; Matthew 20:23)

Against this identification is that the same passages in Mark and Matthew cast James and John in a negative light for seeking prominence for themselves. It appears that “church tradition” deprecated them for seeking a high status that was denied them. If so, it would seem unlikely that they fit the profile of the two witnesses in Revelation 11.

A more recent attempt to revive the James and John identification (Oberweis, 1998) holds that early Christians would easily have associated the sons of Zebedee with the two olive trees standing before God and on the right and left of the lamp-stand: Zechariah 4:2-11. Luke 9:54 explicitly links James and John with the intent to bring down fire from heaven. Moses and Elijah are said to make their appearance in the company of James and John in the transfiguration scene of Mark 9:2-8.

Unfortunately for that thesis, all the writings we have about the fates of James and John inform us that they were martyred by Jews, not by the Romans. That fact alone would surely undermine any possibility of James and John being the two witnesses.

Can Peter and Paul be made to fit the account of Rev 11:3-13? Johannes Munck thought so:

In other words, it was not possible to find two figures that belonged together as two, but it was necessary to put one and one together and to reckon that this would result in two. The Jewish forerunners of the Messiah can bear a certain resemblance to the witnesses in the Apocalypse; this is especially true of Elijah, in that they are preachers, that they call to repentance. On the other hand, the witnesses are not forerunners of the Messiah: it is the Antichrist whose coming they herald. And finally, the witnesses die and rise from the dead, but this is not narrated by any of the Old Testament figures that have been invoked.

In this situation, where the interpretations proposed so far cannot explain the text, I take the liberty of presenting a new interpretation of the passage. I propose to understand the two witnesses as the apostles Peter and Paul, the apostolic witnesses and martyrs in Rome. It is not without hesitation that I propose a new interpretation of the passage, which has already had so many interpretations, the most diverse of which have already been recognised as useless. But the advantages of this new interpretation are that, as far as I know, for the first time we get two witnesses who are really united as one by common martyrdom. Furthermore, in this way it becomes possible to explain the connection of the witnesses with the Antichrist and their resurrection and ascension after martyrdom. . . . (Munck, 15f)

Again there are objections:

Peter and Paul were said to have been martyred in Rome; the two witnesses die in Jerusalem. Munck’s response is that nothing apart from the last part of verse 8 (where also their Lord was crucified) indicates that the two witnesses died in Jerusalem and that stronger reasons are needed to establish Jerusalem as the original setting.

Another objection is that we know of no tradition that said Peter and Paul were killed and then resurrected, as is the case with the two witnesses.

Finally, according to the letters of Paul, the Acts of the Apostles and the letter of 1 Clement, Peter and Paul did not work and act together. The two witnesses are found together for 1260 days — a scenario that defies all that we know of the careers of Peter and Paul.

Another view steps back from a Christian interpretation, at least as we generally understand the meaning of Christian. Klaus Berger writes of the high priests Ananus and Jesus:

It is possible that behind the elaboration of this prophecy [Revelation 11:3-13] there is a reminiscence of the death of the two high priests Ananus and Jesus as described in Josephus, Bell IV 314-317: After conquering the entrance to the city, the first aim of the enemies had been to seize and kill the two high priests. In their impiety the enemies had gone so far, ὥστε καὶ ἀτάφους ῥῖψα [= threw out their corpses without burial] (“although the Jews take such precaution about burial that they also take down and bury those crucified on account of condemnation before sunset”); after 318 the Jews then saw “the leader of their own salvation” (ἡγεμόνα τῆς ἰδίας σωτηρίας) ἐπὶ μέσης τῆς πόλεως . . . ἀπεσφαγμένον [see perseus.tufts.edu for Greek text in context and hyperlinks to translation]. The picture is highly consistent with Rev 11:8[their dead bodies shall lie in the street]. Josephus then writes a laudatio on both high priests. In 323 the whole process is understood as God’s doing, namely as a purifying punishment for apostasy and defilement. Indeed, numerous details in Rev 11:3 ff also point to a priestly group of bearers. Historical “background” may therefore have been made the pattern of eschatological events, similar to what happens with the statements about Antiochus IV in Daniel 7 in the later Daniel Apocalypse (cf. also Lk 19:14), without, however, the possibility of a simple derivation. For the report of Josephus does not contain a special theology of martyrdom. (Berger, 27 – translation)

Here is the passage in Josephus (Whiston translation):

(314) But the rage of the Idumeans was not satiated by these slaughters; but they now betook themselves to the city, and plundered every house, and slew every one they met; (315) and for the other multitude, they esteemed it needless to go on with killing them, but they sought for the high priests, and the generality went with the greatest zeal against them; and as soon as they caught them they slew them, (316) and then standing upon their dead bodies, in way of jest, upbraided Ananus with his kindness to the people, and Jesus with his speech made to them from the wall. (317) Nay, they proceeded to that degree of impiety, as to cast away their dead bodies without burial, although the Jews used to take so much care of the burial of men, that they took down those that were condemned and crucified, and buried them before the going down of the sun. (318) I should not mistake if I said that the death of Ananus was the beginning of the destruction of the city, and that from this very day may be dated the overthrow of her wall, and the ruin of her affairs, whereon they saw their high priest, and the procurer of their preservation, slain in the midst of their city. (319) He was on other accounts also a venerable, and a very just man; and besides the grandeur of that nobility, and dignity, and honor of which he was possessed, he had been a lover of a kind of parity, even with regard to the meanest of the people; (320) he was a prodigious lover of liberty, and an admirer of a democracy in government; and did ever prefer the public welfare before his own advantage, and preferred peace above all things; for he was thoroughly sensible that the Romans were not to be conquered. He also foresaw that of necessity a war would follow, and that unless the Jews made up matters with them very dexterously, they would be destroyed; (321) to say all in a word, if Ananus had survived, they had certainly compounded matters; for he was a shrewd man in speaking and persuading the people, and had already gotten the mastery of those that opposed his designs, or were for the war. And the Jews had then put abundance of delays in the way of the Romans, if they had had such a general as he was. (322) Jesus was also joined with him; and although he was inferior to him upon the comparison, he was superior to the rest; (323) and I cannot but think that it was because God had doomed this city to destruction, as a polluted city, and was resolved to purge his sanctuary by fire, that he cut off these their great defenders and well-wishers, (324) while those that a little before had worn the sacred garments, and had presided over the public worship; and had been esteemed venerable by those that dwelt on the whole habitable earth when they came into our city, were cast out naked, and seen to be the food of dogs and wild beasts. (325) And I cannot but imagine that virtue itself groaned at these men’s case, and lamented that she was here so terribly conquered by wickedness. And this at last was the end of Ananus and Jesus.

For Witulski, what is significant about Berger’s ideas is that they open up the possibility of seeing two Jewish figures (as distinct from Christian ones) behind the two witnesses. With Berger it becomes conceivable that the author was referring to Jewish leaders.

Still, the same kinds of objections that we have seen raised against other proposals remain for the case of Ananus and Jesus: they were not killed by Romans but by Idumeans; and Josephus knows nothing of them being resurrected and ascending to heaven.

What about James the son of Zebedee and James the head of the church (Acts 15) and brother of the Lord (Gal 1)? (A. Greve has advanced this possibility though I am unable to locate his Danish article online.) James the brother of John and son of Zebedee was murdered by Herod Antipas in 44 CE according to Acts 12:2. From Eusebius (among others) we learn of the death of James the Righteous/Just around 62 CE by Jews.

It is difficult to accept Greve’s proposal given that these two men were murdered years apart and neither by the “beast from the abyss”.

The fifth pair cited by Witulski — Jesus and John the Baptist — comes from O. Bücher and once again I am unable to locate online the title (Johannes der Täufer) referenced by W. The justification for these names is that John the Baptist is associated with Elijah and at one time is even mistaken for Elijah redivivus in the gospels while Jesus is often depicted as another Moses. Recall that Elijah and Moses are two of the templates upon which the two witnesses are based, as we saw above. Bücher, furthermore, like many others, claims that the last part of Rev 11:8 – where also their Lord was crucified – should be dismissed as an interpolation, a conclusion that Witulski finds “ultimately linguistically unjustifiable”.

You know the objections by now. Jesus may have been killed by the Romans but it is difficult to make a clear case that the same was true of John the Baptist. Nor do the gospel traditions allow us to think of Jesus and John working together as equal partners.

The Problems with identifying historical candidates

Revelation 11:7 is a sticking point for all of the above proposals. None of them can be made to fit the situation of that verse:

Now when they have finished their testimony, the beast that comes up from the Abyss will attack them, and overpower and kill them.

The other significant difficulty is understanding how any of the above proposals can be related to Revelation 11:11ff

11 But after the three and a half days the breath of life from God entered them, and they stood on their feet, and terror struck those who saw them. 12 Then they heard a loud voice from heaven saying to them, “Come up here.” And they went up to heaven in a cloud, while their enemies looked on.

13 At that very hour there was a severe earthquake and a tenth of the city collapsed. Seven thousand people were killed in the earthquake, and the survivors were terrified and gave glory to the God of heaven.

Conclusion

Given the overall thrust of Revelation insofar as it is addressed to readers concerning pressures they are facing “now”, one must expect that the two witnesses refer to persons appearing at the time the apocalypse was written. Symbolic interpretations must be set aside. Witulski thus presents the background to his own argument for the identification of these mysterious figures. We can expect a somewhat different approach to many of the above claims when W observes . . .

Furthermore, it is noticeable that suggestions for the identification of the two eschatological μάρτυρες are often made without first having analysed the pericope Rev 11,3ff. in its structure and argument. (17 – translation)

Thomas Witulski’s approach to the eleventh chapter of Revelation is that it is part of a letter addressed to specific addressees at a specific time by a specific author: that author, the apocalyptist, was responding to contemporary events, particularly in the Roman province of Asia, but also more widely with respect to events known to his readers. From this perspective, the events described in coded form in Revelation 11 were identifiable to the first recipients of the “letter”.

Wilhelm Bousset (1896, 1906) has continued to influence a number of scholars that Revelation is a collage of fragments with the final editor having only a minor role in production of the content. Witulski briefly refers to Udo Schnelle and his citation of Jürgen Roloff in his introductory section but since I encounter readers online in various forums mentioning the “fragmentary” hypothesis as if it were the standard today, I will quote from the English translation of Schnelle in full:

9.6 Literary Integrity

The apparent lack of connections between the messages to the seven churches of Rev. 2-3 and the main apocalyptic section Rev. 4-22 has repeatedly led to attempted solutions along the lines of source analysis and the literary prehistory of the document. From this approach the messages to the seven churches are regarded either as a later addition, or as the earliest section of Revelation. The essential argument in both cases is the differing perspectives of the messages to the churches and the apocalyptic body of the work: in the former only local persecution, while the latter pictures a time of universal distress. However, the numerous points of contact between the two sections in both composition and content . . . speak against the hypothesis that the Revelation originated in a series of separate stages.

The kind of source hypotheses that flourished around the turn of the century has found little acceptance in recent exegesis. The theory that a redactor had taken up an earlier Jewish apocalyptic document and edited it from a Christian point of view has now been generally abandoned. The only such hypothesis that attained any lasting influence has been that of W. Bousset, who advocated a ‘fragments hypothesis.’ ‘We do not accept the idea of an original document that was gradually expanded, nor was there a collection of original sources edited by a mechanical redactor. Rather, there was an apocalyptic author, but an author who at several points did not compose freehand, but reworked older apocalyptic fragments and traditions, the prehistory of which remain tentative and obscure.’ 60 This model takes the complex history of traditions in the background of the Apocalypse seriously (see 9.7 above), and stands apart from the hypothesis of an original document with later editing by its flexibility and openness.61 More plausible is the view that apparent tensions originated from the heterogeneous (and partly written) materials and[!] the redactional tendencies of the author. ‘As far as its composition as a whole is concerned, Revelation should be seen as a uniform, consistently-constructed work that from beginning to end reflects the theological intention of its author.’ 64 (Schnelle, 530f — emphasis is added by Witulski in his German language text)

This approach to the work — that we have a work authored at one time (not a series of revisions) with different sources tied together by a common theological program and an “obvious linguistic homogeneity” — renders compilation theories or theories that imagine an early work that was repeatedly revised over time seem highly improbable.

Witulski’s approach then will be based on the assumption of the fundamental literary integrity of Revelation —

although this cannot and should not exclude from the outset that later hands may have intervened in the text of the already existing Apocalypse and revised or edited it (21 – translation)

Those sorts of corruptions to the text will be few in number and will need to be justified.

From these starting principles Witulski will proceed with a literary analysis of the text in order to prepare for the interpretation of Revelation 11 in the light of events contemporary with the author.

Before resuming those posts, however, I will write about a book that I recently received taking a different look at the literary sources of the Gospel of Mark.

Schnelle, Udo. The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings. Translated by M. Eugene Boring. Minneapolis, Mn: Fortress Press, 1988.

Witulski, Thomas. Apk 11 und der Bar Kokhba-Aufstand : eine zeitgeschichtliche Interpretation. Tübingen : Mohr Siebeck, 2012. http://archive.org/details/apk11undderbarko0000witu.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The studies that argue for the “integrity” or “unity” of various NT books have always frustrated me. They’re complicated messes that make unity theses always doomed to be picked apart. Revelation might be the apex of this, always stubbornly opaque even when a seeming moment of clarity shines through. That obscurity might be the only “integrity” I would accept.

I wrote a paper about 1 John a decade ago that argued the author or authors were being deliberately vague about what constituted best behavior to their immediate audience while at the same time cutting out the antichrists, who would have been quite aware of what the schism constituted. I called this “polemical ambiguity” rather than obscurantism, however, as it’s not quite the same technique.

… The fifth pair cited by Witulski — Jesus and John the Baptist — comes from O. Bücher and once again I am unable to locate online the title (Johannes der Täufer) referenced by W.

References are:

1) Rechtfertigung, Realismus, Universalismus in biblischer Sicht : Festschr. für Adolf Köberle zum 80. Geburtstag – Otto Böcher, Johannes der Täufer in des neutestamentlichen Überlieferung https://archive.org/details/rechtfertigungre0000unse/page/45/

2) Theologische Realenzyklopädie (ed. Gerhard Müller) Bd. 17. (1988) sub voce “Johannes der Täufer. I. Religionsgeschichtlich” by Böcher, Otto.

But I’d read that in light of

Strömholm, D., “The Riddle of the N.T.”, in The Hibbert Journal (A Quarterly Review of Religion) 24.4 (1925-26), pp. 626ss. https://archive.org/details/sim_the-hibbert-journal-a-quarterly-review-of-religion_1925-1926_24_4/page/626/

&

Strömholm, D., “The Riddle of the N.T.”, in The Hibbert Journal (A Quarterly Review of Religion) 25.1 (1926-27), pp. 53ss. https://archive.org/details/sim_the-hibbert-journal-a-quarterly-review-of-religion_1926-1927_25_1

John the Baptist & Jesus would then be two faces of the same Messiah/Christ : the O.T-al one & the N.T-al one…

Thank you for the reference. I see I should have checked again with the archive.org text to see if my copy/paste of Bücher was correct — I should have been looking for Böcher, as you point out. (Since corrected in the post.) Sometimes it can take a lot of work to find a particular text in archive.org. So much more value could be added to that collection with more systematic metadata.

Yes, the Strömholm articles are an entire case-study of their own.

Do you have a full reference for “A. Greve”? I can have a go at finding a copy for you.

That would be wonderful if you could, and thank you for offering. You can read the original citation at https://archive.org/details/apk11undderbarko0000witu/page/324/mode/2up?q=DTT&view=theater

DTT is Dansk Teologisk Tidsskrift — the online archives for that journal don’t extend back to 1977.

I’ve put in the request. It may take a while since it’s the holidays.

I hope you are staff or student and that the service is free to you.

Don’t worry. It’s free to everyone as long as within a Danish collection.