Recent posts relating to King Josiah’s reforms:

The past few posts have set out the grounds that different scholars have either accepted the historicity of Josiah’s reforms (with varying degrees of certainty) or rejected it.

What we read of Josiah in 2 Kings 22-23 has engendered many questions, problems and hypotheses — theological, textual and historical. In this post I set out some of the various solutions to those questions.

First, recall a few of those problematic questions:

- Josiah is said to be one of the “good kings” of Judah, even the best since David. He is said to have restored the “true worship” of God and rid the land of idols. But then we read that Pharaoh kills Josiah and God punishes Judah by sending them into exile because of the sins of his long-dead predecessor!

- When Josiah hears the words of the book that was discovered in the temple he tears his robes and weeps. Because of his contrition the prophetess promises him a peaceful death. But his end was not peaceful at all. As mentioned above, we read that Pharaoh killed him.

- The prophetess even tells the king that God is going to punish the people of Judah and there is no indication of any hope for them. Yet we read that Josiah proceeds to lead the people in mass repentance — all in vain. God still punishes them. What was the point of the reforms and covenant renewal?

- Why do we read that Josiah felt it necessary to consult the prophetess about the book found in the temple when it is clear that he understands the message of the book very well and he acts on it accordingly?

- When we read about Josiah’s list of reforms we sense a disconnect from all that has gone before. There is no reference at all to those reforms having anything to do with the discovery of the book of the law.

- Later passages in the book of Kings imply that Josiah was one of the “bad kings”. This negative evaluation of Josiah is also found in the books of Jeremiah and Zephaniah. Why was his major reform of returning Judah to God ignored?

Proposed Solutions

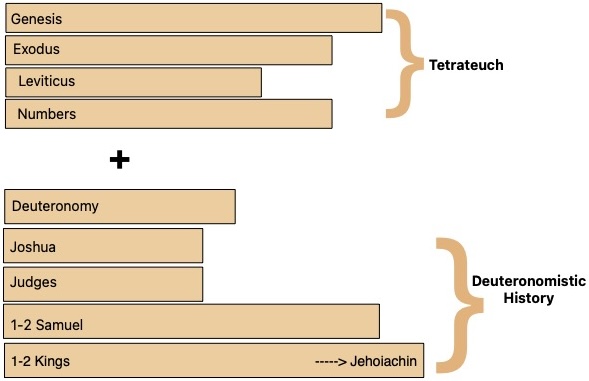

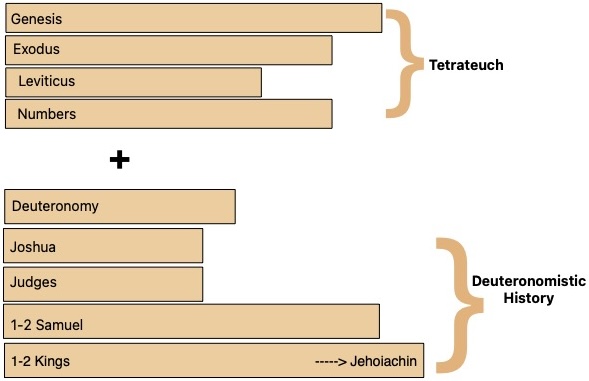

Up to the 1940s scholars had generally looked at the first six books (Genesis to Joshua) as a self-contained unit with the following historical books being tied to those six with only a minimum of editorial commentary. The Pentateuch (Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers-Deuteronomy) began with promises of the land of Canaan to the patriarchs and the book of Joshua (the sixth book) told of how those promises were fulfilled. Hence the Hexateuch made cogent sense: it began with the promises being made and concluded with them being fulfilled. The historical books from Judges to 2 Kings were of quite a different set of styles and themes.

Martin Noth broke with that assumption and analysis and influenced many to follow or only slightly modify his arguments. For Noth, the historical books through to 2 Kings began with Deuteronomy. An editor or editors had before them existing writings about the law, Joshua’s conquests, various judges, prophets and kings, and they brought these works together into a narrative unity, joining and interrupting the various segments with commentary that reflected key themes and ideology found in Deuteronomy. The result was “a Deuteronomistic history” that, despite some bright moments along the way, was doomed to end in disaster.

Noth’s Deuteronomistic editor(s)/author(s) was working with sources already in existence but these were augmented. The original book of Deuteronomy, for example, was thought to only include our chapters 5 to 30 but Noth’s Dtr (the standard abbreviation for this person or persons) added introductory and concluding chapters that addressed core themes found interspersed throughout the ensuing historical books.

One of the most conclusive and least disputed findings of scholarly literary criticism is that in the books of Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings we are confronted with the activity of a Deuteronomistic author in passages both large – sometimes very small. Like all the other historical books in the Old Testament, this author’s work is anonymous, but we call him the “Deuteronomistic” author because his language and way of thinking closely resemble those found in the Deuteronomic Law and in the admonitory speeches which precede and follow the Law. Broadly following present academic practice, we shall refer below to this author and his work by the abbreviation Dtr.

It is generally considered that Dtr. is by a single “Deuteronomistic editor”, or rather by different “Deuteronomistic editors” closely resembling one another in their style . . . . (Noth, 4)

This style is distinguished by its simplicity, fluency, and lucidity and may be recognized both by its phraseology and more especially by its rhetorical character. . . .

The deuteronomic phraseology revolves around a few basic theological tenets such as:

1. The struggle against idolatry

2. The centralization of the cult

3. Exodus, covenant, and election

4. The monotheistic creed

5. Observance of the law and loyalty to the covenant

6. Inheritance of the land

7. Retribution and material motivation

8. Fulfilment of prophecy

9. The election of the Davidic dynasty . . .

What makes a phrase deuteronomic is not its mere occurrence in Deuteronomy, but its meaning within the framework of deuteronomic theology. . . .

The most outstanding feature of deuteronomic style is its use of rhetoric. This is true of all forms of deuteronomic writing. . . . (Weinfeld, 1-3)

For over 40 pages of specific instances of Deuteronomistic style and rhetoric see Weinfeld’s Appendix A on archive.org

What is that style and theological flavour identified as Deuteronomistic? For a detailed answer by Moshe Weinfeld to that question see the extracts and link in the side box.

Our interest here is on the core theme of that history. For Noth, the story was a story of failure. The people of Israel time and time again apostatized from the Deuteronomist’s true worship and, from the vantage point of the author/s, ended their days in exile from their land. The northern tribes of Israel were deported by the Assyrians and the southern kingdom of Judah was exiled into Babylonia. Maybe it could be called a morality tale. Beware, we can see what has happened because of transgression of the laws of Yahweh. So beware.

Though highly influential, Noth’s interpretation seemed to be too easily dismissive of other more positive moments in that history. Were not the promises made to David that his dynasty would last forever unconditional? Does not the final chapter of Kings provide a hint of future hope with the raising of the captive king of Judah to royal favour? And how can one explain the glorious time of Josiah’s reformist rule?

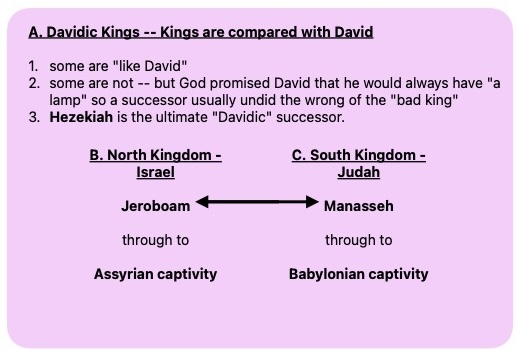

Frank Moore Cross proposed another explanation for the combination of hope and despair in the Deuteronomistic history. For Cross, the first historical books were written or at least shaped in the gloriously hopeful days of good king Josiah. The historical work ended on a high note: Judah had repented, Josiah had cleansed the land of idolatry, and a king as great as David was once more on the throne. Sadly, a few kings later (587 BCE) and Judah was overrun by Babylon’s Nebuchadnezzar, Jerusalem and its temple were destroyed, and a large portion of the population were deported. Around the middle of the sixth century another scribe, reflecting on the disaster that had overtaken Judah since the time of Josiah, picked up the historical tale and added the chapters of apostasy and failure following the time of Josiah.

Cross’s proposal had the advantage of somewhat explaining how the anomaly of the record of Josiah’s righteousness sat so awkwardly prior to the final doom of Judah. But if the evidence for the historicity of Josiah’s reforms is scant to non-existent, why is it included at all? And how do we account for other oddities in the Josiah narrative, some of which I listed at the beginning of this post?

Other scholars have proposed other refinements: Helga Weippert has suggested there were three redactions. The first Deuteronomist editor concluded the history with Hezekiah’s reforms; the second with Josiah’s reforms; and the third with the fall of Jerusalem. Rudolf Smend identified three different hands working over the same material: the first Deuteronomist redactor completed the historical book so that it concluded with the demise of the kingdom of Judah and its Babylonian exile; the second worked through the existing text by adding prophetic commentary and speeches and documenting their fulfilment; while the third worked at making the importance of the Deuteronomistic law more prominent at key points. There are other variants. Too many — and that’s the reason there has been such a wide gap between this post and my previous one: I have been tracking down and taking on board many of these various explanations — only to set most of them aside so I could conclude this series.

But there is a common thread through all of these proposed explanations. They view Josiah’s reforms as an unremovable fact of history that must be included despite the problems this raises in relation to their beliefs in God’s justice. They scarcely account for the difficulties raised by the Josiah portrait — a good king who leads his people in repentance is cast aside without his promised reward and the people are punished for the sin of a long-dead king.

An Alternative

But what happens if we consider the likelihood that Josiah never undertook any reformist program: that possibility has been raised in recent posts (see above). What happens if we imagine the historical chronicle without any mention of Josiah’s reforms? What if the first historical rendering did not conclude with Josiah’s reform but, knowing nothing of that reform, proceeded to trace the final demise of Judah and its Babylonian captivity?

In other words, What happens if we treat the Josiah reform story as a late interpolation into the earlier doomsday narrative?

Before answering that question, notice that there are reasonable grounds for suspecting it to be a valid scenario.

Possibly the most striking evidence that the Josiah reforms were not written by the same deuteronomistic author/s responsible for the larger and final portrayal is its violation of a fundamental premise of Deuteronomy: that repentance leads to forgiveness and mercy. Up until the story of Josiah the consistent message we have read is that if kings turn away from the sins of their predecessors they can avoid God’s wrath. Josiah completely undid the sins of his predecessor Manasseh:

| Manasseh (2 Kings 21:3-6) |

Josiah (2 Kings 23:4, 8, 10, 12) |

| 3 He rebuilt the high places his father Hezekiah had destroyed; he also erected altars to Baal and made an Asherah pole, as Ahab king of Israel had done. He bowed down to all the starry hosts and worshiped them.

4 He built altars in the temple of the Lord, of which the Lord had said, “In Jerusalem I will put my Name.”

5 In the two courts of the temple of the Lord, he built altars to all the starry hosts.

6 He sacrificed his own son in the fire, practiced divination, sought omens, and consulted mediums and spiritists. . . .

|

4 The king ordered Hilkiah the high priest, the priests next in rank and the doorkeepers to remove from the temple of the Lord all the articles made for Baal and Asherah and all the starry hosts. He burned them outside Jerusalem

8 Josiah . . . desecrated the high places, from Geba to Beersheba, where the priests had burned incense. . . .

10 He desecrated Topheth, which was in the Valley of Ben Hinnom, so no one could use it to sacrifice their son or daughter in the fire to Molek. . . .

12 He pulled down the altars the kings of Judah had erected on the roof near the upper room of Ahaz, and the altars Manasseh had built in the two courts of the temple of the Lord. . . . |

Scholars have written at length about the problems raised by the cruel fate of Josiah and the nation despite their wholehearted turning to Yahweh. It is often thought that among the exiles there emerged a crisis in understanding the ways of God. Rationalizations abound, but there is little evidence in any of the biblical writings to support these revisionist notions about the justice and will of God. Some scholars have seen in Josiah a foreshadowing of the death of a righteous messiah. The first difficulty with that interpretation is that in the story of the discovery of the book of the law the prophetess Huldah assures him he will die in peace. One more rightly must conclude that we have a text whose parts were written by authors “not talking to each other”.

There are other pointers to an interpolation. Immediately after the death of Josiah we read of the next king, Jehoahaz, that

He did evil in the eyes of the Lord, just as his predecessors had done. (2 Ki 23:32)

Then of the following king, Jehoiakim, we read

And he did evil in the eyes of the Lord, just as his predecessors had done. (2 Ki 23:37)

Did not the author recall that immediately prior to these kings was a predecessor who was the greatest and most righteous king of all since David? How could that author lump Josiah in with those who had done evil just like all the rest?

Further …. we have other writings referring to Josiah yet are oblivious to any righteousness associated with his reign. One of these is the book of the prophet Jeremiah and the other is that of Zephaniah.

The only prophecy that the book of Jeremiah directly dated “in the days of king Josiah” was Jer. 3.6-11, in which the idolatrous whoredoms of faithless Israel (Samaria) were said to have been exceeded by her unrepentant sister Judah. Additionally, the book of Jeremiah stated that Jeremiah’s prophecies and warnings over a period of 23 years from the thirteenth year of Josiah to the fourth year of Jehoiakim went entirely unheeded. The Jewish people were destined for punishment for their disobedience and their having violated the divine covenant. Repentance by the Jewish nation or its kings could have averted disaster, but none took place in the years leading up to the fall of Jerusalem. Indeed, the rise of Nebuchadnezzar was the direct result of the utter lack of repentance of the Jews during the preceding 23 years of Jeremiah’s prophetic activity (Jer. 25.1-14). It was precisely the utter lack of reform during those years that signaled doom for Jerusalem. There is thus not the slightest hint that Jeremiah’s author(s) were acquainted with changes in religious practices prompted by a purported discovery of the book of the law in Josiah’s eighteenth year. Quite the contrary, Jeremiah’s prophecies against Jerusalem and its rulers starting in the reign of Josiah were unremittingly negative and Jeremiah had nothing favorable to say of any of Judah’s kings after the time of Hezekiah. . . .

A speech in Jer. 44.2-30 to the exiles in Egypt contains significant literary parallels to the regnal evaluations of the last kings of Judah: the speech twice referred back to abominable sins committed in Judah and Jerusalem by their “fathers” and by “the kings of Judah” who made offerings to other gods, committed abominations, ignored the laws and statutes and did evil in the sight of Yahweh (Jer. 44.9-10, 21-24). This negative evaluation of the people of Judah, their ancestors and their kings forms a close verbal parallel to the negative evaluation of Jehoahaz, Jehoiakim and their ancestors. Both painted a negative picture of the last kings of Judah and neither was compatible with Josiah or his generation having walked in obedience to the laws of Yahweh, especially in the matter of worship of other gods.

(Gmirkin, 15f, 29f)

and

A similar picture of Josiah may be inferred from the book of Zephaniah, whose prophecies were dated to “the days of King Josiah son of Amon of Judah” (Zeph. 1.1). Zephaniah predicted the coming of the day of the Lord to punish Jerusalem and make the land desolate, brought on as a result of idolatrous practices (Zeph. 1.4-6) and violence against the law (Zeph. 3.1-4). Jerusalem would not accept correction (Zeph. 1.4, 6; 3.1, 7); the kings’ sons and royal officials were singled out as sinners destined for punishment (Zeph. 1.8; 3.3). While these prophecies are connected to the figure of Zephaniah only in the Deuteronomistic superscription, one may reasonably infer that at the time the superscription was created, the Deuteronomistic editor knew nothing about the reign of Josiah that would rule out assigning these prophecies to his time. Specifically, the charges of Baal and Molech worship in Josiah’s days at Zeph. 1.4-5 appear to indicate that the Deuteronomistic editor was unaware of the cultic reforms of 2 Kgs 23.29

29 Attempts to harmonize Zephaniah and 2 Kings 23 typically overcome this difficulty by postulating that Zephaniah was written early in Josiah’s reign, prior to his initiation of cultic reforms. Such an approach assumes that both Zephaniah and 2 Kings 23 were both ancient, authentic witnesses to historical events under Josiah. It is preferable to maintain the literary integrity of both texts by acknowledging their dissonant content.

(Gmirkin, 16)

So it appears from evidence both within the book of 2 Kings and in writing outside 2 Kings that at some point there was no knowledge of the Josiah reforms currently in 2 Kings 23.

The alternative I am setting out here is entirely from Russell Gmirkin’s article published in the Journal of Higher Criticism over two years ago. It is available to all on his academia.edu page. You can read the full argument there.

Another piece of evidence that the 2 Kings 23 recital of Josiah’s reforms were not part of the original work is found in the comparison of Josiah with Moses. The comparison with David and the reminders of God’s promises to David is part of the Deuteronomistic language (see the insert box above and instances of the Davidic notices by the Deuteronomist in Weinfeld’s list at archive.org). Richard Elliot Friedman has detailed the allusions to Moses in Josiah’s portrayal, although note that Friedman is not himself arguing that the Josiah episode is an interpolation. He in fact concurs with Cross’s view (above) that the Josianic reform was the conclusion of the original book of Kings and argues that with Deuteronomy and references to Moses it formed an inclusio to the entire history. But the comparison of Josiah with Moses implicitly nullifies the comparison with David who cannot match the status of Moses. In the table below I have restricted the comparison of Josiah to the person of Moses and not to other passages relating to the law in Deuteronomy.

| Moses |

Josiah |

| “There did not arise a prophet again in Israel like Moses . . .” (Deut 34:10) |

“There was no king like him before him turning to Yhwh with all his heart and with all his soul and with all his might according to all the Torah of Moses, and after him none arose like him” (2 Kings 23:25). – REF acknowledges Jack R. Lundbom for observing this allusion |

| Moses burns and smashes the golden calf “thin as dust,” . . . and casts the dust on the wadi . . . (Deut 9:21). |

At the site of Jeroboam’s golden calf of Bethel, Josiah smashes the [high place] and burns it, “and he made it thin as dust . . .” (2 Kgs 23:15).

Josiah burns the statue of Asherah which Manasseh had set in the Temple, at the wadi Kidron, “and he made it thin as dust . . .” (23:6). The phrase [“made it thin as dust”] occurs nowhere but in the passages noted here. Josiah also smashes the altars which his ancestors had made and casts their dust into the wadi (v 12). |

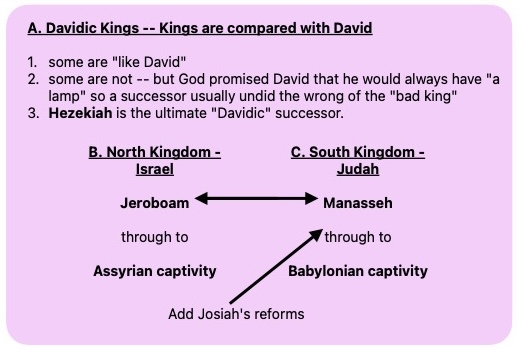

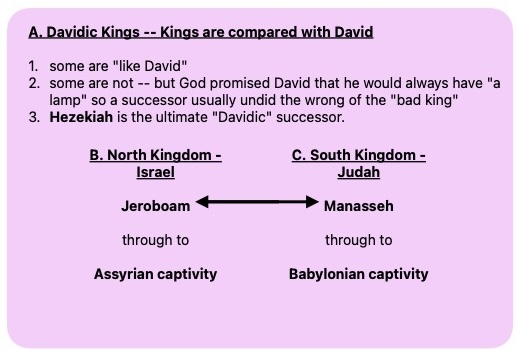

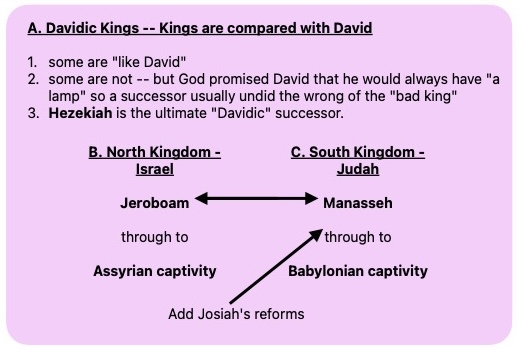

I have illustrated other proposals with diagrams. Here is one that helps us visualize what the biblical record looks like if the Josiah reform narrative were never part of the original deuteronomistic history. The first writing did not include or conclude with Josiah’s reforms. Rather, Josiah was among the “bad kings” that marked Judah’s decline after the good Davidic king Hezekiah. The story outline of the final chapters of 2 Kings is thus:

The Davidic Kings keep David’s “lamp” alight until Hezekiah; after Hezekiah the new king, Manasseh, followed the ways of the wicked king Jeroboam of Israel; Manasseh and Jeroboam are alike (for the extensive parallels between these two figures see Gmirkin, p.34), and both lead their kingdoms to ruin: Jeroboam set Israel on the path to Assyrian captivity and Manasseh set Judah on the path to Babylonian captivity.

The discovery of the book of the law in the temple of God was included in this anecdote as a classic final doomsday warning. This is not only a common enough motif in ancient literature but it is also the explicit reason Moses had the book of the law placed in the ark of the covenant. Recall Deuteronomy 31:24-29 —

24 After Moses finished writing in a book the words of this law from beginning to end, 25 he gave this command to the Levites who carried the ark of the covenant of the Lord: 26 “Take this Book of the Law and place it beside the ark of the covenant of the Lord your God. There it will remain as a witness against you. 27 For I know how rebellious and stiff-necked you are. If you have been rebellious against the Lord while I am still alive and with you, how much more will you rebel after I die! 28 Assemble before me all the elders of your tribes and all your officials, so that I can speak these words in their hearing and call the heavens and the earth to testify against them. 29 For I know that after my death you are sure to become utterly corrupt and to turn from the way I have commanded you. In days to come, disaster will fall on you because you will do evil in the sight of the Lord and arouse his anger by what your hands have made.”

The prophetess speaks the words of “a female Jeremiah” (Jeremiah 19:3, 11, 25:7, and 7:20 — the comparison is Christoph Levin’s – p.366) and echoes the above words of Moses. The purpose of the book was not to provoke repentance but was to testify mercilessly against king and nation:

15 She said to them, “This is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: Tell the man who sent you to me, 16 This is what the Lord says: I am going to bring disaster on this place and its people, according to everything written in the book the king of Judah has read. 17 Because they have forsaken me and burned incense to other gods and aroused my anger by all the idols their hands have made, my anger will burn against this place and will not be quenched.’ (2 Kings 22:15-17)

Indeed, Russell Gmirkin’s case for the favourable presentation of Josiah is that it arose only after the completion of the book of Jeremiah:

It was only after the book of Jeremiah was completed that a new literary tradition arose in which Josiah was recast as a Deuteronomist reformer extraordinaire. Once both 2 Kgs 22-23 and the book of Jeremiah are understood as late literary accounts rather than archaic historical accounts, the problem of determining the relationship of the two becomes a simple matter of literary analysis rather than a torturous exercise in historical speculation, as in most past attempts to reconcile Jeremiah and Kings. It is only under the assumption that the reforms of Josiah described in 2 Kings and the prophecies of Jeremiah in Jer. 1-25 were both grounded in historical fact that a compelling need to reconcile the two literary traditions arises.

(Gmirkin, 21f)

Josiah’s reforms are an anomaly at many points:

- they violate the theology of the Deuteronomist author who promised salvation to the repentant;

- they are contradicted by independent works, Jeremiah and Zephaniah;

- they are contradicted by the ensuing text in 2 Kings that refer to the sins of the last kings of Judah;

- they present Josiah as a figure who stands beyond comparison with David (viz. with Moses);

- the blame placed on Manasseh for the Babylonian captivity only makes sense if Josiah was originally among the “bad kings” — or if the author added an explanation that Judah apostatized after Josiah’s death (Gmirkin, 28);

- the archaeological evidence indicates “business as usual” regarding worship of Asherah and idols at Josiah’s time.

I have skimmed the surface of the far more detailed arguments of Russell Gmirkin’s proposal by which the many problems of the Josiah report in 2 Kings 22-23 can be resolved. But one more salient feature must be added.

The book of the law that witnesses against king and nation is not the same one that Josiah acts upon. Or rather, the creator of the righteous Josiah had a different kind of book in mind from the one in the original judgement narrative. Rather than the book of the law that witnessed against the sins of the people, the author states that Josiah is acting on “the book of the covenant”. The covenant restored by Josiah culminated in a mass observance of the Passover and this aligns with the vignette of the Mosaic covenant at Sinai. God came down to show himself to Moses once more after he had broken the first stone tablets:

10 Then the Lord said: “I am making a covenant with you. Before all your people I will do wonders never before done in any nation in all the world. The people you live among will see how awesome is the work that I, the Lord, will do for you. 11 Obey what I command you today. I will drive out before you the Amorites, Canaanites, Hittites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites. 12 Be careful not to make a treaty with those who live in the land where you are going, or they will be a snare among you. 13 Break down their altars, smash their sacred stones and cut down their Asherah poles. 14 Do not worship any other god, for the Lord, whose name is Jealous, is a jealous God. . . .

17 “Do not make any idols.

18 “Celebrate the Festival of Unleavened Bread. For seven days eat bread made without yeast, as I commanded you. Do this at the appointed time in the month of Aviv, for in that month you came out of Egypt. (Exodus 34)

As did Josiah…

Then the king called together all the elders of Judah and Jerusalem. 2 He went up to the temple of the Lord with the people of Judah . . . . He read in their hearing all the words of the Book of the Covenant, which had been found in the temple of the Lord. 3 The king stood by the pillar and renewed the covenant in the presence of the Lord—to follow the Lord and keep his commands, statutes and decrees with all his heart and all his soul, thus confirming the words of the covenant written in this book. Then all the people pledged themselves to the covenant.

21 The king gave this order to all the people: “Celebrate the Passover to the Lord your God, as it is written in this Book of the Covenant.” (2 Kings 23)

So we can add here a seventh point on which the Josianic reforms sit anomalously with the broader text: the book of the law with its pronouncement of curses has been redescribed as a book of covenant renewal.

How it happened

- The original document consistently set forth the sins of the kings in the wake of Hezekiah’s son Manasseh. The discovery of the book of the law in the temple was a climactic moment pronouncing the ultimate curses that were about to fall upon the nation.

- Another scribe, presumably unaware or only partially aware of that original writing, independently composed a biography of Josiah as an ideal king restoring a utopian covenant renewal with Yahweh.

- When that scribe (or another closely associated one) learned of of the detail whereby the prophetess delivered the curses from the book of the law, an additional scenario was added in which Josiah repented and a new statement by the prophetess was added acknowledging Josiah’s righteousness.

- When an editor decided to add this new idealistic biography of Josiah to 2 Kings, they made a few adjustments to “make it fit” between 2 Kings 22:1 and 2 Kings 23:verses but failed to create a smooth transition leading to his death and the subsequent notes about the wickedness of all kings in the wake of Manasseh.

A literary analysis of the closing chapters of 2 Kings thus provides evidence for multiple Deuteronomistic authors.

(Gmirkin, 87)

Conclusion

Russell Gmirkin is best known for his books setting forth the evidence for a Hellenistic provenance of the Hebrew Bible. If his arguments are sound then the traditional view that the book of Deuteronomy and a deuteronomistic history were authored or revised in the days of Josiah and soon after in the exilic period must be set aside.

An alternate model of Deuteronomistic authorial and editorial activity literary activity is to view it as the product of a relatively small group of Deuteronomist authors working contemporaneously and collaboratively. The interrelationship of [the original Josiah account and the subsequent somewhat clumsy Josiah reforms additions] already points to this conclusion. Given that the entire corpus of Deuteronomistic texts display awareness of Jerusalem’s fall and anticipate a return of exiles to the land of Judah, this would seemingly point to a date for this Deuteronomistic activity after ca. 450 BCE and conceivably as late as the early Hellenistic Era when we have the first external evidence for the book of Deuteronomy (the LXX of ca. 270 BCE), Kings (Demetrius the Chronographer, ca. 221-204 BCE) and Jeremiah (Dead Sea Scroll fragment 4QJera palaeographically dated to ca. 225-175 BCE). If we take these texts as roughly contemporary, this points to a date no later than ca. 270 BCE. The Deuteronomists should thus be situated within a relatively brief time span falling sometime within the period ca. 450-ca. 270 BCE.

(Gmirkin, 95)

Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Friedman, Richard Elliot. “From Egypt to Egypt: Dtr1 and Dtr2.” In Traditions in Transformation: Turning Points in Biblical Faith, edited by Baruch Halpern and Jon D. Levenson, 167–92. Winona Lake, Ind. : Eisenbrauns, 1981. http://archive.org/details/traditionsintran0000unse.

Gmirkin, Russell. “The Manasseh and Josiah Redactions of 2 Kings 21-25.” Journal of Higher Criticism, January 1, 2022. https://www.academia.edu/82084563/The_Manasseh_and_Josiah_Redactions_of_2_Kings_21_25.

Levin, Christoph. “Joschija Im Deuteronomistischen Geschichtswerk.” Zeitschrift Für Die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 96, no. 3 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.1984.96.3.351.

Noth, Martin. Deuteronomistic History. Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1981 [1943].

Provan, Iain W. Hezekiah and the Books of Kings: A Contribution to the Debate about the Composition of the Deuteronomistic History. Berlin New York: De Gruyter, 1988.

Weinfeld, Moshe. Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic School. Eisenbrauns, 1992.

Weippert, Helga. “Die ‘Deuteronomistischen’ Beurteilungen Der Könige von Israel Und Juda Und Das Problem Der Redaktion Der Königsbücher.” Biblica 53, no. 3 (1972): 301–39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42610051

Like this:

Like Loading...