Concluding an overview of Peter Kivisto’s discussion of “institutional openings to authoritarianism” in the USA. See Kivisto for the complete series. (Images, bolding, formatting, other sources are my additions.) The takeaway for me in Kivisto’s discussion is the pivotal role racism has played in enabling the presidency of Donald Trump. Little did I suspect that the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s would lead what we see today in the political landscape. For another relevant perspective on Obama’s terms in office see the posts on Nancy Fraser’s From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump – and Beyond. .

. . . . Republican Representative Joe Wilson upended congressional decorum by shouting that Obama was a liar while the President was giving a speech to a joint session of Congress. . . .

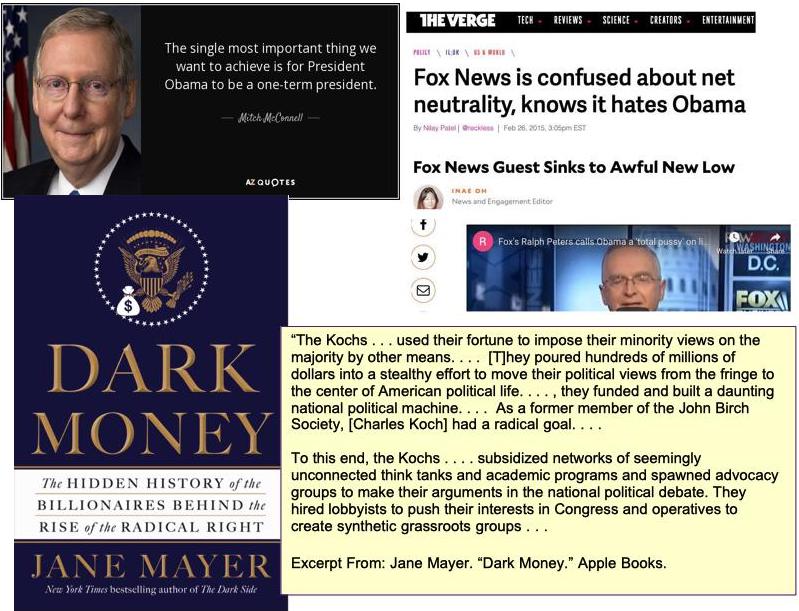

.. . . . The Republican leader in the Senate quickly promised that the one objective of Senate Republicans would be to insure that Obama would not be re-elected, and to that end rejected bipartisanship at every turn. The right-wing media savaged him relentlessly, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported disturbing increases in the size and activities of right-wing hate groups, and funds from right-wing plutocrats flowed freely to mobilize the grassroots. . . .

Obama had been exceedingly careful — too careful for many of his supporters’ tastes — in addressing issues about race. Moreover, he had to simultaneously confront two crises, the first being the blowback caused by the disastrous Bush/Cheney invasion of Iraq and the second being the global financial crisis that began in 2007. Much of his agenda reflected both the need to respond carefully to these inherited problems, but beyond that he pressed what was essentially a pragmatic center-left set of proposals. His one major ambitious plan called for building on the New Deal and Great Society programs in addressing the fact that the United States was the only wealthy liberal democracy in the world that did not treat health care as a universal entitlement. He sought to expand health care coverage, reduce costs, and implement best practices that would make for a more efficient and effective health delivery system. And in so doing, rather than pressing for a single-payer system akin to Canada’s or expanding Medicare to cover all Americans, he hoped for a plan that would elicit bipartisan support. To that end, the plan he proposed bore a family resemblance to one developed by a conservative think tank in the 1990s and a plan that Mitt Romney created in Massachusetts during his tenure as governor. Obstructionism would make bipartisanship impossible, and thus the Affordable Care Act was passed without a single Republican vote in either chamber of Congress.

In this context, the Tea Party came to represent the crystallization of citizen opposition to Obama. The intensity of their vehement hostility to Obama can be understood by the fact that as right-wing populists, their enemies were twofold:

- elites — governmental and academic, but not business

- — and the congeries of “Others,” including blacks, immigrants, Muslims, and freeloaders. . . .

. . . . He was the black usurper, his white mother in the end being irrelevant to this particular trope. He was the noncitizen, born in Kenya. He was the closet Muslim. At the same time, the Harvard Law graduate and part-time professor at the University of Chicago was a member of the elite liberal intelligentsia. Those who identified as strong Tea Party supporters, amounting to perhaps one-fifth of the electorate, were vocally unwilling to see Obama as a legitimate President.

Much discussion ensued about the precise character of the Tea Party. Was it a genuine grassroots movement or was it of the Astroturf variety, the product of the Koch brothers and other right-wing plutocrats? In The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism sociologists Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williamson see it as both, observing that “one of the most important consequences of the widespread Tea Party agitations unleashed from the start of Obama’s presidency was the populist boost given to professionally run and opulently funded right-wing advocacy organizations devoted to pushing ultra-free-market policies.” These include FreedomWorks, the Club for Growth, the Tea Party Express, and Americans for Prosperity. The last of these is the creation of the Koch brothers, a nonprofit political advocacy organization. Its funders have spent millions pushing to privatize Social Security, voucherize Medicare and Medicaid, slash taxes, roll back environmental laws, and crush labor unions. For example, the organization shaped Governor Scott Walker’s assault on public sector unions in Wisconsin and has been a central player in shaping Rep. Paul Ryan’s agenda to roll back the welfare state. As oversight organizations promoting transparency have repeatedly pointed out, these operations are prime examples of the impact of dark money from wealthy right-wing donors who are able to keep their identities anonymous while spending freely to influence public policy.

Skocpol and Williamson succinctly summarize the purpose of these activities, writing that, “After the 2008 election, the Koch brothers and their organizational allies were determined to do all they could to limit, humiliate, and defeat Barack Obama and other Democrats in the US Congress and the states, majority democracy be damned.” Along with rightwing think tanks such as the American Enterprise Institute, but particularly with the more extremist and strident Cato Institute and Heritage Foundation, these forces came to constitute the main drivers of Republican Party agendas. They also contributed heavily to congressional races, the result being the growing impact within the party of what is known today as the Freedom Caucus, composed of about 30 Republican House members. The defeat of Eric Cantor in Virginia by the even more right-wing David Brat was indicative of the rightward movement of the party.

Among the rank and file, activists often claimed that they were newcomers to the political process, outsiders who felt compelled by the clear and present danger the Obama presidency represented to get involved as patriots in defense of the nation. Such was not the case. In the main, these were longterm Republican Party members, their political views shaped by white nationalism, Christian nationalism, or by some combination thereof. In a 2011 report the Pew Research Center found that Tea Party members originate disproportionately from the ranks of white evangelical Protestants. On economic issues, they differ from the population as a whole by overwhelmingly preferring smaller government and by believing that corporate profits are fair and reasonable. On social issues, they differ from registered voters in general by opposing same-sex marriage and abortion at a higher level, while also being far more likely to oppose gun control. It is perhaps due to the religious backgrounds of so many Tea Party members, people who would claim to interpret the Bible literally as the inerrant word of God, that movement rhetoric about the Constitution was similarly reverential, treating it as a sacred text (Skocpol & Williamson, 2012, p. 48). And like Biblical literalists, they presumed to be able to interpret the Constitution in similar ways, dispensing with the ambiguities of language or a felt need to recognize the salience of historical context.

| REVERENCE FOR THE CONSTITUTION

A tour of Tea Party websites around the country quickly reveals widespread determination to restore twenty-first century U.S. government to the Constitutional principles articulated by the eighteenth-century Founding Fathers. The Lynchburg Tea Party of Virginia, for example, sums up the “principles that we adhere to” as “Constitutionally Limited Government”; “Freedom to Pursue Prosperity through unhindered Markets”; and “Liberty tempered by Virtue.” Far to the north, the “About Us” page of the Maine Tea Party/Maine ReFounders website features “Pete the Carpenter” explaining that “We are fighting to preserve our Constitution, Country and hold true to the visions of our founding fathers.” Likewise, thousands of miles into the U.S. heartland, meeting on the third Thursday of each month at the Eagles Club in a small town in the northwestern corner of Nebraska, the Crawford Tea Party describes itself simply as “a group of concerned citizens . . . who desire to see a restoration of Constitutional government.” Just as Rick Santelli invoked Founding Fathers to excoriate an Obama mortgage-assistance measure, so do Tea Party groups across America link their present-day activities to a constantly restated reverence for the country’s founding documents: the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the Declaration of Independence. Skocpol, Theda, and Vanessa Williamson. 2016. The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism. Oxford : New York: Oxford University Press. p. 48 |

After Obama’s reelection, the Tea Party looked to some observers to be a spent force. However, Skocpol, writing in 2013, correctly contended that it “wasn’t going anywhere,” and in fact maintained political influence at both the national and state levels. She concluded by making the following important point: “Americans may resent the Tea Party, but they are also losing ever more faith in the federal government — a big win for anti-government saboteurs. Popularity and ‘responsible governance’ are not the goals of Tea Party forces.” In this regard, they clearly set the stage for Trump. Despite at one time being fierce advocates of limited government when confronted by what they described as a power-grabbing executive during the Obama years, they, ironically, were happy to support someone projecting himself as an autocratic strongman. Likewise, once proponents of a neo-liberal embrace of unfettered global capitalism found themselves equally enamored of economic protectionism during the 2016 campaign season. What didn’t change was their visceral hostility to political enemies and to those who they had denied membership in the ranks of “the people.” Writing in 2016, journalist Kate Aronoff correctly concluded that, “The infrastructure that paved Trump’s road to electoral success was built largely by the Tea Party.”

In a multiparty parliamentary system, right-wing populists would have created their own parties to compete in electoral politics — as has been going on in Western Europe for over three decades. In the US, context politics has long been dominated by two major parties, with third-party efforts never amounting to more than symbolic protests incapable of achieving actual political power. Thus, the triumph of rightwing populism required the takeover of the Republican Party. Whereas the extremist right had been successfully kept at arm length in the two decades after World War II, the Southern strategy and the entry of a politicized Christian right [links are to the previous Vridar posts in this series] made the takeover possible. The deal was sealed when liberal and moderate Republicans either left or were forced out.

Right-wing populists are by now very much in control the party, running it, however, without widespread support among the electorate at large. How is this possible? Part of the reason has to do with the historically deeply entrenched electoral system that is, simply put, insufficiently democratic. Beyond that reality, Republican success at gerrymandering Congressional districts has created many safe seats for right-wing extremists. And a well-established part of the Republican playbook today is voter suppression. While the Voting Rights Act of 1965 made possible the exercise of the franchise by previously excluded minority groups, it has been met by a relentless campaign to make voting difficult or impossible. This campaign was greatly assisted by the victory of the conservative faction of the Supreme Court in 2013 to whittle away at the provisions of the law. And several states were quick to jump on this decision to enact laws that disproportionately and negatively impacted minority and poor voters. Finally, since the Reagan administration, the delegitimizing of government has contributed to the withdrawal from civic involvement, including voting, for a large plurality of the nation’s adult citizens.

Many of the people in this group of disengaged citizens are the most economically vulnerable members of society, and Republican leaders know that if they voted with their own self-interest in mind, they would be unlikely to support a right-wing populist agenda. Thus, their success in achieving their reactionary goals is predicated in no small part on the ability to instill in these potential voters a sense of cynicism and fatalism. The electoral victory of Trump, who many on the right viewed as flawed but potentially useful, was made possible by these fundamental assaults on the democratic process and on the culture of democracy.

Kivisto, Peter. 2017. The Trump Phenomenon: How the Politics of Populism Won in 2016. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing. pp. 101-106

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!