…

…

Avi Shlaim in The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World writes that Israel’s escalation of tensions on the Syrian front prior to June 1967 was the “single most important factor dragging the Middle East to war”. Prior to the war news stories told again and again of Syrian’s firing at Israeli farmers from the Golan Heights but the full circumstances of those conflicts was not revealed publicly until 1997 when a reporter published notes of his interview with the military commander Moshe Dayan in 1976. In that interview

Avi Shlaim in The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World writes that Israel’s escalation of tensions on the Syrian front prior to June 1967 was the “single most important factor dragging the Middle East to war”. Prior to the war news stories told again and again of Syrian’s firing at Israeli farmers from the Golan Heights but the full circumstances of those conflicts was not revealed publicly until 1997 when a reporter published notes of his interview with the military commander Moshe Dayan in 1976. In that interview

Dayan confessed that his greatest mistake was that, as minister of defense in June 1967, he did not stick to his original opposition to the storming of the Golan Heights. Tal began to remonstrate that the Syrians were sitting on top of the Golan Heights. Dayan interrupted,

Never mind that. After all, I know how at least 80 percent of the clashes there started. In my opinion, more than 80 percent, but let’s talk about 80 percent. It went this way: We would send a tractor to plow someplace where it wasn’t possible to do anything, in the demilitarized area, and knew in advance that the Syrians would start to shoot. If they didn’t shoot, we would tell the tractor to advance farther, until in the end the Syrians would get annoyed and shoot. And then we would use artillery and later the air force also, and that’s how it was. I did that, and Laskov and Chara [Zvi Tsur, Rabin’s predecessor as chief of staff] did that, and Yitzhak did that, but it seems to me that the person who most enjoyed these games was Dado [David Elazar, OC Northern Command, 1964–69].

(Shlaim, 250f)

The Road to War

According to the evidence in Shlaim’s study neither side wanted the 1967 war. There was no conspiracy by Arab states to launch a surprise attack on Israel and Israel had no plan to seize extra territory at the time. War came about as a consequence of political miscalculations and blunders, or a “crisis slide that neither Israel nor her enemies were able to control.”

Stage 1 – careless threats in media interviews

To begin with, Israel made a series of threats against the Syrian regime unless it stopped its support for Palestinian guerillas:

- 11 May 1967, Israel’s director of military intelligence in a briefing of foreign journalists “gave a distinct impression that Israel was planning a major military move against Syria.”

- Then the Chief of Staff of the Israeli Defense Forces dropped a hint published in an Israeli newspaper “that the aim might be to occupy Damascus and topple the Syrian regime.”

Stage 2 – cornered into a show of leadership

The Soviet Union, supporter of the Syrian government, in response sent a report to Syria’s ally Egypt to warn that Israel was moving its forces towards the northern border and planning to attack Syria. Egypt’s president, Nasser, was pressured to take some decisive action to maintain his credibility as leader of the Arab nations:

The report [from the USSR] was untrue and Nasser knew that it was untrue, but he was in a quandary. His army was bogged down in an inconclusive war in Yemen, and he knew that Israel was militarily stronger than all the Arab confrontation states taken together. Yet, politically, he could not afford to remain inactive, because his leadership of the Arab world was being challenged. . . . Syria had a defense pact with Egypt that compelled it to go to Syria’s aid in the event of an Israeli attack. Clearly, Nasser had to do something, both to preserve his own credibility as an ally and to restrain the hotheads in Damascus. There is general agreement among commentators that Nasser neither wanted nor planned to go to war with Israel. (252f)

Nasser decided on three-fold action to impress the Arab public:

1. He sent a large force into the Sinai

2. He ordered the removal of the U.N. peacekeepers from the Sinai

3. He closed the Straits of Tiran to Israel shipping

Stage 3 – the psychological hit

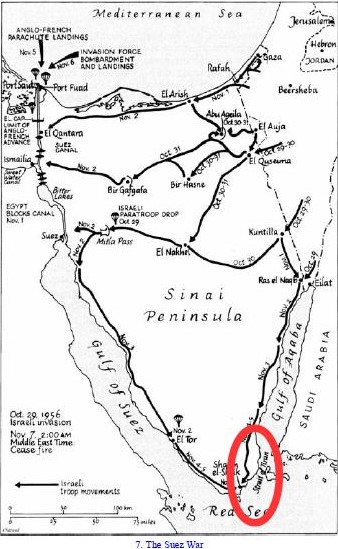

It was #3 that rankled in Israel the most since the Straits were the prize gain of the Israeli forces in the 1956 Suez War:

For Israel this constituted a casus belli. It canceled the main achievement of the Sinai Campaign. The Israeli economy could survive the closure of the straits, but the deterrent image of the IDF could not. Nasser understood the psychological significance of this step. He knew that Israel’s entire defense philosophy was based on imposing its will on its enemies, not on submitting to unilateral dictates by them. In closing the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, he took a terrible gamble—and lost. (253)

Stage 4 – collective psychosis

According to Shlaim the Israeli government was paralyzed for two whole weeks with indecision. The lack of leadership led to public panic:

During this period the entire nation succumbed to a collective psychosis. The memory of the Holocaust was a powerful psychological force that deepened the feeling of isolation and accentuated the perception of threat. Although, objectively speaking, Israel was much stronger than its enemies, many Israelis felt that their country faced a threat of imminent destruction. For them the question was not about the Straits of Tiran but about survival. Weak leadership was largely responsible for permitting this panic to spread from the politicians to the people at large. (253)

Stage 5 – threat of the religious party

Israel’s political impasse was resolved on 1 June with the formation of a national unity government. But the National Religious Party threatened to withdraw from the coalition unless the outspoken and belligerent Moshe Dayan was put in charge of the Defense Ministry.

Warnings against: Continue reading “The Golan Heights: the Myth versus the Historical Record”