As we discussed several months ago, Michael Licona wrote a book about the differences in the gospels in which he tries to explain them away by comparing the evangelists to Plutarch. However, his attempt was stillborn, since his methodology contains a deadly flaw. He proposes that by examining how Plutarch changed stories as he recounted them in different Lives, we can gain some insight as to how the author of Luke, for example, edited Marcan stories.

In the latter case, of course, we can see only how Luke dealt with one of his sources. In the former, we discover how Plutarch rewrote himself. These are two different things. But before we toss Licona’s book aside, let’s consider how we might apply his methodology correctly. Is there any place in the New Testament in which an author created a second work and plainly rewrote one or more stories in a way that might resemble Plutarch’s process?

Resuscitation Redux

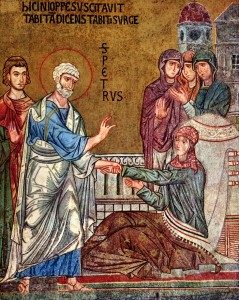

Yes. In the Acts of the Apostles, the author (whom most scholars believe is the same person as the author of Luke) recycled stories told about Jesus and applied them to Peter. You probably already noticed long ago that Jesus raised a young girl (Mark provides the Aramaic talitha) in Luke 8:40-56, while Peter raised a female disciple named Tabitha (Aramaic for antelope or gazelle) in Acts 9:36-42. And no doubt you thought to yourself, “That sounds familiar.”

The author (we’ll call him Luke for the sake of convenience) has left other clues that we’re reading the same story, albeit with different characters set in a different locale. By examining the Greek text, we can discover textual affinities between the two stories.

Acts 9:36 Now there was in Joppa a disciple named Tabitha, which, translated, means Dorcas. She was full of good works and acts of charity. (NASB)

Acts places several important events in Joppa, because historically this town acted as the port city for Jerusalem. Legend has it that the cedars of Lebanon floated via the sea to Joppa, and then were shipped overland to Jerusalem. Joppa is the physical and metaphorical gateway from Judea to the Greco-Roman world.

Luke tells us Peter learned all animals are now clean while visiting Simon the Tanner in Joppa. This fable seeks to explain the change from a faction based in Judaism, with its understanding of what is ritually unclean to God (pork, blood, foreskins, etc.), to something new — a splinter cult on the path to a separate religion that fell back on the so-called Noahide Covenant.

From Jairus to Joppa

Hence, Joppa is the transition point. It represents the legendary compromise between the two major factions in the early days of the church from which orthodox Christianity arose.

In this gateway city, we learn of a young woman who is known by her Aramaic and Greek names. In Luke’s gospel, which provides the source for the story in Acts, we never learn the young girl’s name. However, both Mark and Luke tell us her father’s name. Jairus, whose name means “whom God enlightens,” was a “ruler of the synagogue.”

Mark 5:22 One of the synagogue officials named Jairus came up, and on seeing Him, fell at His feet. (NASB)

Luke 8:41 And there came a man named Jairus, and he was an official of the synagogue; and he fell at Jesus’ feet, and began to implore Him to come to his house; (NASB)

According to one legend, Joppa was named after Noah’s son, Japheth, whose name (depending on which translation you go with) means “God will increase.” Recall the curse from Genesis:

God shall enlarge Japheth [a pun?], and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. (Genesis 9:27, KJV)

Luke, then, has changed the venue from an inward-looking, Jewish story that occurs in the house of a synagogue leader to an outward-looking Gentile story in a city named for the eponymous ancestor of the nations that will occupy the lands of the Semites. He has moved the story from the people God has enlightened to the people God will increase.

When the author of Matthew retold Mark’s story, he abbreviated it severely. We lose the name of the synagogue leader, whose daughter has already died when he approaches Jesus. But Luke, while he does shorten the story somewhat, retains most of the elements, including the suspense (Will Jesus make it to Jairus’s house in time to save her?), the age of the young girl, etc.

“If I could at least . . .”

In fact, Luke placed the story of the Gerasene Demoniac directly before the Raising of Jairus’s Daughter, and he maintained the Marcan sandwich, in which the Woman with the Issue of Blood interrupts Jesus. Here we see strong evidence of literary dependence. Luke has copied Mark. But has he taken anything from Matthew as well?

We find one possible indicator that Luke used Matthew in the omission of Mark’s dramatic aside from the woman in Mark 5:28: “If I just touch his clothes, I will be healed.” (NIV) It would appear that Luke edited out this line, and instead of reaching for Jesus’ garments, she touches the mere “fringes.” (We’ve discussed earlier here at Vridar that by a fringed garment Luke probably meant a tallit.)

But check out the wording in Luke 8:44a:

προσελθοῦσα ὄπισθεν ἥψατο τοῦ κρασπέδου τοῦ ἱματίου αὐτοῦ

having come behind touched the fringe of the clothing of him

And compare it to the wording in Matthew 9:20b:

προσελθοῦσα ὄπισθεν ἥψατο τοῦ κρασπέδου τοῦ ἱματίου αὐτοῦ

having come behind touched the fringe of the clothing of him

Mark 5:27 is different:

ἐλθοῦσα ἐν τῷ ὄχλῳ ὄπισθεν ἥψατο τοῦ ἱματίου αὐτοῦ

Having come in the crowd behind touched the clothing of him

As always, scholars have concocted many explanations for such minor agreements in Matthew and Luke. But the simplest reason would be that Luke copied Matthew.

In any case, I would now draw your attention to a word in Acts that occurs only once, namely the adverb κἂν [kan], which, depending on the context, can mean just, only, or at least.

For she thought, “If I just [kan] touch His garments, I will get well.” (Mark 5:28, NASB)

. . . to such an extent that they even carried the sick out into the streets and laid them on cots and pallets, so that when Peter came by at least [kan] his shadow might fall on any one of them. (Acts 5:15, NASB)

In both cases, we have desperately ill people trying to find relief without the laying on of hands. (Recall that Jesus’ healing touch was exactly what Jairus had begged for, at least according to Mark (5:23) and Matthew (9:18).) Touching just the edge of Jesus’ clothes would somehow discharge power and heal the bleeding woman. In Acts, of course, the author has upped the ante. The sick don’t even need to touch a material object; they need only have Peter block the sun as he walks by. Just his shadow heals them. In either case, we’re dealing with rare instances of passive healing.

Cots and pallets

We have more clues in the second verse above that the author of Acts knew and used Mark’s gospel. The word the KJV translates as “couch” — κλινίδιον [klinidion] — is a diminutive of “bed” and is found only in Luke-Acts. Some English versions translate this word as “stretcher.” In the story of the paralytic let down through the roof, Luke substituted Mark’s word for “pallet” (κράββατος [krabattos]) with his word for “stretcher.”

Being unable to get to Him because of the crowd, they removed the roof above Him; and when they had dug an opening, they let down the pallet on which the paralytic was lying. (Mark 2:4, NASB)

But not finding any way to bring him in because of the crowd, they went up on the roof and let him down through the tiles with his stretcher, into the middle of the crowd, in front of Jesus. (Luke 5:19, NASB)

Here, the NASB translators decided to use the word stretcher instead of couch or cot, presumably to give the reader a better visual impression. In Mark, several translations use the word mat instead of pallet, which sounds rather odd, but is probably more accurate. (Note: The NIV translators render both Greek words as “mat,” because harmonizing the gospels is apparently a worthy goal.)

They let him down through the roof on a mat? We can’t help but wonder, “How was he lowered on a thin bed that you can roll up and stow away?” Perhaps Luke thought the same thing when he changed it to a word that means something like “a small cot with a frame.”

Mark used krabbatos five times, but neither Matthew nor Luke ever kept that word when they copied him in their gospels. They seem to have considered it substandard Greek, or at least not the best word for the job. In Acts, however, we get both cots and pallets. Luke may have considered krabbatos a sort of crass or provincial word, and perhaps by putting both words together he wished to unify the hicks in Galilee and Judea with the sophisticated urbanites of the Greco-Roman world.

“You ask, ‘Who touched me?!'” — Peter Takes Charge

Luke’s edit of Mark subtly changes who responds to Jesus when he asked who touched him.

And Jesus, immediately knowing in himself that virtue had gone out of him, turned him about in the press, and said, Who touched my clothes? And his disciples said unto him, Thou seest the multitude thronging thee, and sayest thou, Who touched me? (KJV, 5:30-31)

And Jesus said, “Who was it that touched me?” When all denied it, Peter said, “Master, the crowds surround you and are pressing in on you!” (Luke 8:45, ESV)

Peter has come to the fore in Luke’s gospel. He speaks for all the disciples. You may have noticed, as well, the subtle change in the order of the three disciples who form Jesus’ inner circle. The first time we meet them, Paul writes:

And when James, Cephas, and John, who seemed to be pillars, perceived the grace that was given unto me, they gave to me and Barnabas the right hands of fellowship; that we should go unto the heathen, and they unto the circumcision. (Gal. 2:9, KJV, emphasis mine)

We could legitimately translate that as “reputed to be pillars,” “supposed pillars,” or even “alleged pillars.” He used the same word –δοκοῦντες (dokountes) — three verses earlier.

And from those who seemed to be influential (what they were makes no difference to me; God shows no partiality)—those, I say, who seemed influential added nothing to me. (Gal. 2:6, ESV, emphasis mine)

Paul turns his nose up at those with supposed authority, those so-called pillars. But Mark re-elevates the supposed pillars to special status. By this time, the reading audience prefers the Greek [Πέτρος (Petros)] over the Aramaic Cephas. And while Paul presents James as the head of the trio, Mark puts Peter in the lead in the trip to the Mount of Transfiguration and in the healing of Jairus’s Daughter.

We would do well to recall, however, that by the end of Mark’s gospel, we find out that Peter denied Jesus in his hour of need. We also discover that James and John wanted special status, much to the consternation of the other disciples, but Jesus sets them straight. (See Mark 10:35-45)

By the time Luke gets around to the pericopae with Peter, James, and John, he has demoted James to third place.

And after six days Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. And he was transfigured before them . . . (Mark 9:2, ESV, emphasis mine)

Now about eight days after these sayings he took with him Peter and John and James and went up on the mountain to pray. (Luke 9:28, ESV, emphasis mine)

I submit that shoving James to the end of the list is no accident.

If you feel the need to tell me these aren’t the same James and John, don’t worry. I’m aware of the need for the authors of the New Testament to reinterpret the various appearances of and references to Peter, James, and John. That’s why we frequently see explanatory epithets such as “whom he named Peter,” “brother of James,” “sons of Zebedee,” and even “brother of the Lord.” Early Christians had trouble keeping it clear. Who is this “Simon” person? Which James? Which John?

Peter the Healer

In Acts, we have reached a new phase. Peter is the dominant character, the vanguard of Christianity. Eventually, he will appear to have passed the baton to Paul as the new religion marches to Rome, but for now Peter is the man.

When Peter arrives at the house where Tabitha’s body lies, everyone is weeping, just as in Luke 8:52. He puts them all outside, just as Jesus did in Luke 8:51.

Peter takes her by the hand after she opens her eyes, while Jesus took her hand from the start, and I think this is an important difference. In Acts, Peter kneels to pray. Then he turns toward the corpse and says “Tabitha, arise!” However, in the gospel story, Jesus takes her hand right away (without praying) and then tells her to get up. Hence, Peter calls on an external force for help, while Jesus contains within himself all the power needed to raise the dead.

Conclusion

We have found a worthwhile use for Licona’s method. It turns out the New Testament does contain recycled narratives written by the same author (assuming the same author wrote both Luke and Acts). In our examples above, we have evidence that Luke borrowed from at least one written work (Mark), and possibly from a second (Matthew). We have further literary evidence that he refashioned one of those borrowed stories, changing the main character from Jesus to Peter, changing Talitha to Tabitha, and moving the scene from Galilee to Joppa.

As you will recall, many scholars think of Luke as a historian and a biographer. The preamble to his gospel, they insist, shows how much he cared about his many sources. Well, perhaps. But we see here that he was quite comfortable with inventing stories, freely repurposing and reusing his sources for his own needs.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“Michael Licona wrote a book about the differences in the gospels”

You’d think the inerrant dictated divine word of god wouldn’t contain so many contradictions – must be that Yahweh, Jesus and the Holy Spook each had their own version they passed along.

Fascinating. I love these sorts of literary analyses. We’ve mentioned the symbolic significance of Joppa before but only from the context of Jonah, if I recall. What sources can you point us to addressing some of the legends associated with Joppa that you refer to here?

People mention it in passing as an old legend.

https://books.google.com/books?id=DYsPAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA597&dq=%22joppa%22+%22japheth%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjMkonp_93YAhVI-qwKHVnYA2AQ6AEIUjAH#v=onepage&q=%22joppa%22%20%22japheth%22&f=false

http://www.jewishmag.com/43mag/jaffa/jaffa.htm

Also, this:

“Jaffa, belle of the seas, ancient city. Japheth, son of Noah, built it and gave her his name. But of all the Greek beauty of Japheth, all that remains is what human beings can’t remove from her, and their city changes with the nature of her inhabitants.”

S.Y. Agnon, Only Yesterday, translated by Barbara Harshav, Princeton University Press.

https://www.amazon.com/Only-Yesterday-S-Y-Agnon/dp/0691095442

clarification required

In Matthew, is the woman with blood problem healed only after Jesus speaks to her or does she get a healing after touching fringe ?

Interesting question. He says her faith cured (perfect indicative) her. So when he utters that line, the cure has already occurred. But was it her having faith or her acting on faith that cured her? Is faith the confession (albeit internal) or the deed?

Whatever the case, Matthew apparently wants to change Mark’s notion of Jesus’ power discharging as if he were a sort of holy capacitor.

Sounds good. But in addition: if we consider the Churches as in effect the corporate authors or editors of the New Testament, then we might actually have another author like Plutarch. Editing, revising, himself. Or coming out with significantly different successive editions.

Repurposing and reusing text or narrative episodes was a literary technique that was employed both in the composition of Josephus’ histories and in the composition of the Gospel attributed to Mark. It can be demonstrated that the miraculous healings in Mark are all variations of a common literary theme. The authors of Luke and Matthew emulated Mark, since their miracle stories also follow a shared outline and have common literary features.

Repurposing and reusing text in Josephus

A Repetitive Literary Formula That Confirms the Testimonium Flavianum is an Interpolation

https://rogerviklund.wordpress.com/2014/07/21/rebels-bandits-frauds-charlatans-and-other-wicked-men-in-the-works-of-flavius-josephus/

Other examples of repurposing and reusing text by the synoptic Gospels

https://rogerviklund.wordpress.com/2012/08/26/the-literary-relationship-of-the-raising-of-lazarus-story-to-the-secret-gospel-of-mark-excerpts-quoted-in-the-mar-saba-letter-of-clement-and-miraculous-healing-stories-in-the-synoptic-gospels/

https://rogerviklund.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/parallel-passages-in-the-gospels-of-secretmark_john_mark_luke-and-matthew.pdf

Also see

https://rogerviklund.wordpress.com/2011/09/29/overlaps-between-secret-mark-the-raising-of-lazarus-in-john-and-the-gerasene-swine-episode-in-mark/