In the previous post, I promised to discuss a group of scholars who changed the perspective of biblical scholarship. I was referring to those whom we commonly group into the religionsgeschichtliche Schule. In English we call this the History of Religions School. The German term, religionsgeschichtliche, implies a secular, critical-historical approach toward religion. The reputation of the History of Religions School has not fared well over the past few decades.

A withering review

For example, in Ben Witherington’s scathing review of Robert Price’s Jesus Is Dead, he writes:

In any case, one of the things that movies like ‘The God who is not There’ and the Zeitgeist movie, and Robert Price’s book have in common is a reliance on the old, and now long since out-dated and refuted notions of the Religionsgeschichte Schule [sic] when it comes to the issue of Jesus and the origins of Christianity. It seems that my former Gordon-Conwell classmate, Bob Price, and various others as well did not get the memo that these sorts of arguments are inherently flawed, have often been shown to be flawed, and shouldn’t be endlessly recycled if you want to argue cogently that Jesus didn’t exist and/or didn’t rise from the dead.

What is the Religionsgeschichte Schule [sic], and why is this school now closed? The history of religions approach to early Christianity, and to Jesus himself, involved as its most foundational assumption that the origins of what we find in the NT in regard to Jesus, resurrection, etc. come from non-Jewish culture of various sorts, particularly from Greco-Roman culture, but also (as the Zeitgeist movie was to remind us) from Egyptian sources. In short, anything but an origin in early Judaism is favored when it comes to explaining the NT and Jesus. (italic emphasis Ben’s, bold emphasis mine)

Just for the sake of accuracy, Religionsgeschichte is a noun; religionsgeschichtliche is the adjectival form. He got it right in the title, but muffed it four times in the body of the review. Still, you have to hand it to him; he actually mentioned it. These days, you’d hardly know the History of Religions School had ever existed, and most scholars don’t — other than it was “flawed” and “refuted” and “outdated.” Just learning those pejorative modifiers would appear to suffice, or at least to keep you in good standing within the guild.

When is a school not a school?

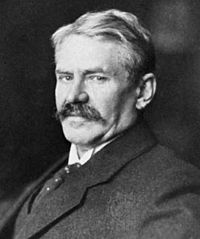

We may find it somewhat difficult to describe a school whose members often insisted there was no school. In “The Dogmatics of the ‘Religionsgeschichtliche Schule,'” Ernst Troeltsch explained: Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 11: Origins of the Criteria of Authenticity (3)”