The first two gospels portray Jesus being anointed by an unnamed woman in Bethany in order to “prepare him for burial.” In the third gospel that scene has been removed and replaced with another, set earlier, of an unnamed woman anointing Jesus’ feet.

The first two gospels portray Jesus being anointed by an unnamed woman in Bethany in order to “prepare him for burial.” In the third gospel that scene has been removed and replaced with another, set earlier, of an unnamed woman anointing Jesus’ feet.

How do we know the Gospel of Luke was rewriting the Bethany anointing scene and not adding a totally different episode? The answer lies in the clues the third evangelist left us. Both scenes share the following:

- Jesus in the house of Simon

- Jesus is reclining at table

- An unnamed woman

- An alabaster jar of ointment

- Others are indignant at what Jesus allows the woman to do

- Jesus and the woman are the only ones who understand the meaning of the event until Jesus explains

And then there are the syzygies, the paired opposites:

- leper and pharisee

- anointing head and anointing feet

- one anointing is of the kind done by a priest to anoint a king; the other by a lowliest servant to welcome a guest

- the monetary value of the ointment is the focus of the offence in one story; the analogous monetary value of “forgiving and loving much” is the lesson presented in the other

- one woman is offered worldly “fame” (though unnamed!); the other woman is given salvation

We have enough DNA to identify Luke’s story as derivative of the one found in Mark and Matthew. (Thomas Brodie further identified 2 Kings 4:1-37 as an additional source.) Clearly the author of the third gospel did not believe he was reading a “historical memory” in the earlier gospel(s) or that he was composing a version of history. The author recognized the earlier narrative as composition with a certain message that could be erased and rewritten in the interests of preaching another message deemed more appropriate.

So what was the alternative message? Why was the theme of the first account “repealed and replaced”?

The answer to that question, I think, is found in the opening chapters of Luke. I wrote about it ten years ago almost to the day (my god time flies!)

The poor and Q — literary vs historical paradigms

The Gospel of Luke stresses from the opening narratives preceding even the birth of Jesus that Jesus is destined to reverse the present order. The lowly will be exalted; the high will be brought low. Mary sings when she is told she will give birth to Jesus:

My soul glorifies the Lord

and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior,

for he has been mindful

of the humble state of his servant.

From now on all generations will call me blessed

. . . .

He has performed mighty deeds with his arm;

he has scattered those who are proud in their inmost thoughts.

He has brought down rulers from their thrones

but has lifted up the humble.

He has filled the hungry with good things

but has sent the rich away empty. . . .

Luke has a special interest in those kinds of reversals. I have listed several of them in my 2007 post.

Mark’s and Matthew’s Bethany anointing scene surely clashes with that interest. In those earlier gospels Jesus effectively says to his outraged audience: “Forget the poor for a moment; just think of me and my greatness for a few minutes.”

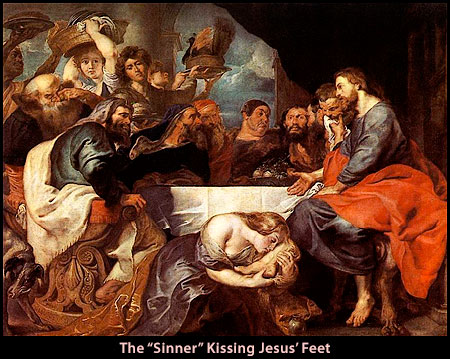

So the anointing scene is removed to a place and occasion where Jesus shows once again how he exalts the sinner and the lowly.

The woman is anointing Jesus’ feet, not his head. She is acting as the lowest servant, not someone with a fortune in her hand who has the honorable task of proleptically anointing the future king. The riches are found in the depth of her love and the corresponding greatness of forgiveness.

| Mark 14 | Matthew 26 | Luke 7 |

| 3 While he was in Bethany, reclining at the table in the home of Simon the Leper, a woman came with an alabaster jar of very expensive perfume, made of pure nard. She broke the jar and poured the perfume on his head.

4 Some of those present were saying indignantly to one another, “Why this waste of perfume? 5 It could have been sold for more than a year’s wages and the money given to the poor.” And they rebuked her harshly. 6 “Leave her alone,” said Jesus. “Why are you bothering her? She has done a beautiful thing to me. 7 The poor you will always have with you, and you can help them any time you want. But you will not always have me. 8 She did what she could. She poured perfume on my body beforehand to prepare for my burial. 9 Truly I tell you, wherever the gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her.”

|

6 While Jesus was in Bethany in the home of Simon the Leper, 7 a woman came to him with an alabaster jar of very expensive perfume, which she poured on his head as he was reclining at the table.

8 When the disciples saw this, they were indignant. “Why this waste?” they asked. 9 “This perfume could have been sold at a high price and the money given to the poor.” 10 Aware of this, Jesus said to them, “Why are you bothering this woman? She has done a beautiful thing to me. 11 The poor you will always have with you, but you will not always have me. 12 When she poured this perfume on my body, she did it to prepare me for burial. 13 Truly I tell you, wherever this gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her.”

|

36 One of the Pharisees asked him to eat with him, and he went into the Pharisee’s house and reclined at table. 37 And behold, a woman of the city, who was a sinner, when she learned that he was reclining at table in the Pharisee’s house, brought an alabaster flask of ointment, 38 and standing behind him at his feet, weeping, she began to wet his feet with her tears and wiped them with the hair of her head and kissed his feet and anointed them with the ointment. 39 Now when the Pharisee who had invited him saw this, he said to himself, “If this man were a prophet, he would have known who and what sort of woman this is who is touching him, for she is a sinner.” 40 And Jesus answering said to him, “Simon, I have something to say to you.” And he answered, “Say it, Teacher.”

41 “A certain moneylender had two debtors. One owed five hundred denarii, and the other fifty. 42 When they could not pay, he cancelled the debt of both. Now which of them will love him more?” 43 Simon answered, “The one, I suppose, for whom he cancelled the larger debt.” And he said to him, “You have judged rightly.” 44 Then turning toward the woman he said to Simon, “Do you see this woman? I entered your house; you gave me no water for my feet, but she has wet my feet with her tears and wiped them with her hair. 45 You gave me no kiss, but from the time I came in she has not ceased to kiss my feet. 46 You did not anoint my head with oil, but she has anointed my feet with ointment. 47 Therefore I tell you, her sins, which are many, are forgiven—for she loved much. But he who is forgiven little, loves little.” 48 And he said to her, “Your sins are forgiven.” 49 Then those who were at table with him began to say among themselves, “Who is this, who even forgives sins?” 50 And he said to the woman, “Your faith has saved you; go in peace.”

|

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Why did John again change the story? Woman. Large quantity of oil. Jesus anointed. Feet as in Luke, but at the supper, Jesus doesn’t use Luke’s metaphor of the exalted being brought low and the lowly being exalted. As in Mark & Matthew, Jesus in John says “you will always have the poor” and then foreshadows (foretells?) his death: “but you won’t always have me.”

Instead, John 13 along with Matthew 26 and Luke 22 make the point about the lowly being exalted, etc. – the reversal – in the next scene, where Jesus washes the disciples’ feet. Luke knows he will be making the point about the reversal later. So, there really was no need for Luke to address the reversal here and no need to make her a sinful woman. He could just be emphasizing the point, I suppose, but in order to make his point he has to change “the woman” (“Mary” in John in John 12:3) into a great sinner, something that doesn’t appear in Mark & Matthew. So again, why was this scene so necessary for Luke? He already had the reversal thing covered.

John adds a twist here because in Matthew and Mark it appears that the container is broken – possibly implying the loss of all the oil. She poured the perfume over him, “to prepare [Him] for [His] burial.” Yet John very specifically says it was a liter of oil (12:3) and implies there is some left over: “Let her keep this for the day of my burial,” which makes more sense if it isn’t an unnamed woman, but Mary who anointed him.

[quotes are slightly paraphrased,]

Two different homes. One was a Leper and the other a Pharisee. One person was a Woman, and the other a Woman of sin. Jesus is saying different things in different situations. These scriptures are God breathed, the authors being inspired by the Holy Spirit. There is no trick or error here.

I agree that there is “no trick or error here” by any means. Not at all. But should we not test the writings bequeathed to us to see if they are God-breathed or human inventions? Is not that what God would want us to do?

“The Gospel of Luke stresses from the opening narratives preceding even the birth of Jesus that Jesus is destined to reverse the present order. The lowly will be exalted; the high will be brought low.”

This change is consistent with my theory that Mark’s original scene was an honor to the aristocrat Flavia Domitilla, who had donated the use of her catacombs to the Roman congregation. That’s why the focus of Mark’s anointing scene is on the amount of money spent on the ointment, and on the worldly honor given to the woman. And why the anointing is like the anointing of a king by a priest.

It looks like Luke knew why Mark had written the scene, and deliberately reversed its meaning. The Flavian family was defunct; Luke had no reason to retain in his text, the honor to Flavia. No one would complain if Luke changed the scene for his own purpose.

Addition: Why did Matthew keep Mark’s scene? Possibly, because Flavia was a Gentile who had given a great gift to a Judean-based congregation, and was remembered as such.

Have you any new thoughts on those Hypsistarians? https://usa1lib.org/terms/?q=theos+hypsistos

Nothing more than what I’ve read in the Athanassiadi/Frede and the Mitchell/Nuffelen volumes.

There was something in a recent post of yours [Hadrian or those 7 kings of revelations/province of Asia stuff] that reminded me of ‘Thracian horseman’ or ‘mounted hero’ motifs that eventually became St. George and the Dragon. It was one night a week back when I was quite tired and nodding off in my chair so I only recall part of a thought now. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thracian_horseman

Will have to go back to reread slowly.

All of those posts are listed at https://vridar.org/tag/witulski-die-vier-apokalyptischen-reiter-apk-6/ (and https://vridar.org/tag/witulski-johannesoffenbarung-und-kaiser-hadrian/)

I thought about something to do with Sabazios while thinking about linguistic etymologies: “*Dyēus was associated with the bright and vast sky, but also to the cloudy weather in the Vedic and Greek formulas *Dyēus’ rain. Although several reflexes of Dyēus are storm deities, such as Zeus and Jupiter, this is thought to be a late development exclusive to Mediterranean traditions, probably derived from syncretism with Canaanite deities and the Proto-Indo-European god *Perkwunos.”

The syncretism with Canaanite deities is an interesting thought. Could really equate the angry sky daddy Yahweh with sky daddies Zeus and Jupiter in the https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interpretatio_graeca game of intercultural translation.

For the mounted on horseback sky daddy “most high” of the Hysistarians “Sabazios (Ancient Greek: Σαβάζιος, romanized: Sabázios, modern pronunciation Savázios; alternatively, Sabadios) is the horseman and sky father god of the Phrygians and Thracians. In Indo-European languages, such as Phrygian, the -zios element in his name derives from dyeus, the common precursor of Latin deus (‘god’) and Greek Zeus. Though the Greeks interpreted Phrygian Sabazios as both Zeus and Dionysus, representations of him, even into Roman times, show him always on horseback, as a nomadic horseman god, wielding his characteristic staff of power.”

The first Jews who settled in Rome were expelled in 139 BCE, along with Chaldaean astrologers by Cornelius Hispalus under a law which proscribed the propagation of the “corrupting” cult of “Jupiter Sabazius”, according to the epitome of a lost book of Valerius Maximus:

Gnaeus Cornelius Hispalus, praetor peregrinus in the year of the consulate of Marcus Popilius Laenas and Lucius Calpurnius, ordered the astrologers by an edict to leave Rome and Italy within ten days, since by a fallacious interpretation of the stars they perturbed fickle and silly minds, thereby making profit out of their lies. The same praetor compelled the Jews, who attempted to infect the Roman custom with the cult of Jupiter Sabazius, to return to their homes.

By this it is conjectured that the Romans identified the Jewish YHVH Tzevaot (“sa-ba-oth”, “of the Hosts”) as Jove Sabazius.

Who wrote the original Letters of Paul? Was he related to the sect described by Pliny the Younger, our first non-apologetic evidence of “Christians”?

I think it is possible that they are related, both Hypsistarians. Throughtout all of human history to the very recent past, a great cultural divide existed between literates and illiterates of the same tribe/ethnic group/family group. Illiterates need stories; they are concrete thinkers. Literates can soar on the wings of philosophy. The texts we have are all preserved by literates. We need other tools than textual analysis to imagine these writers’ contexts, which include illiterate people.

I would like to see speculation based on the following:

1. Knowledge of human psychology regarding religious beliefs and worship. For example, i suggest scholars apply what I call the one-step rule: People change their beliefs one step at a time; when they are comfortable with the result of taking one step, they may take another step. (Instant, voluntary conversion to a new idea is extremely rare.) Any historical reconstruction must not assume rapid voluntary conversion of anyone to a substantially different idea.

2. Knowledge of how religion is expressed in societies that are oral+semi-literate, and oral + semi-literate + literate. The literates’ religion is not the entire story; literates have illiterate children, wives, and slaves. What kind of pressure does that family configuration put on the literates? How do they ‘keep the peace’? (I suggest that Jesus of Nazareth was in part a solution to the influx of often-affiliated illiterates into a formerly Gnostic sect.) (Note: I haven’t read the books from your search). I see “pagan monotheism” as a solution to the literates’ problems of reconciling their monotheism with 1) the concrete thinking and narratives of illiterates, and 2) the Great-Spirit-All-Is-One belief of illiterates.

3. Knowledge of how ideas diffuse between cultures, e.g., what makes one religion ‘win’ over another, the time scale of diffusion, how technologies (e.g., re writing, travel) affect diffusion.

In summary, go beyond textual analysis: generalize from insights from social psychology, anthropology and sociology. Not enough of that in biblical studies.

Indeed, I very much like the idea of bringing anthropological and psychological studies of religious belief into the discussions of Christian origins. And origins of Judaism, too. I did explore a while back works by Harvey Whitehouse in particular (but others, too) and try to keep some of that reading in mind when thinking through questions of origins. Those kinds of studies would surely help frame better hypotheses, but I wonder if we have sufficient evidence to test them very thoroughly.

I think these tools are more useful for rejecting hypotheses than for testing hypotheses that are “possible,” e.g., my proposal that Pliny’s Christians and Paul belonged to the same ethnic group. Even so, there are too many hypotheses that require disbelief in the ordinary behavior of humans.

Re: my proposal that Pliny’s Christians and Paul belonged to the same ethnic group

How would Paul have come by his Roman citizenship? https://depts.drew.edu/jhc/eisenman.html The possibilities are few in that period on the periphery far from Rome.

Your suggestion that Jesus of Nazareth was in part a solution to the influx of often-affiliated illiterates into a formerly Gnostic sect is quite interesting.

I think I once sent this to you or someone here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28774258/

The assertion that “Paul” was a Roman citizen comes from Acts “(Acts 16:37-38, Acts 22:25-28). In the latter passage, Paul states that he was born a Roman citizen. His citizenship status is the reason he can successfully appeal to the emperor (Acts 25).” – https://www.bibleodyssey.org/en/tools/ask-a-scholar/paul-and-roman-citizenship

In my opinion, Luke has two motivations for making his character Paul a citizen: mainly, it is a plot device to get Paul to Rome (where he is again an equal of Peter). It also raises Paul’s status.

Re the hand of Sabazios, it is suggestive to say the least for a Judaic/Samaritan influence in the area (Sabazios/Tzvaot).

The original Paul could have been a Roman citizen, but Luke’s motivation to portray him as one is so strong that, to me, the citizenship is most likely fictional.

Didn’t Paul/Saul like going to Cyprus because his mother was from there? https://markandmore.wordpress.com/2007/06/12/desposynoi-part-2/

However these puzzles are solved I still see it as all bullshit at the end of the day being in the Gmirkin, Wajdenbaum, & Company camp that says it is all pious fictions and noble lies cobbled together as Plato advised.