Sometimes I discover the most curious things en route to learning something else. I can’t even remember why now, but for some reason, I recently stumbled upon the definition of pericope (peh-RIH-kuh-pee) at the Oxford Biblical Studies Online site.

If you’ve read my posts on the Memory Mavens, you’re no doubt aware that I sometimes refer to a common practice in current NT studies wherein scholars tend to associate concepts, ideas, and even words they don’t like with form criticism. By such association, they dismiss anything they find offensive. “Don’t touch that,” they imply. “It has form-critical cooties.”

Resurrected?

Here’s an unexpected example from Oxford:

pericope

A term used in Latin by Jerome for sections of scripture and taken over by form critics to designate a unit, or paragraph, of material, especially in the gospels, such as a single parable, or a single story of a miracle. (emphasis mine)

Reading that definition, you might get the impression that Rudolf Bultmann and Martin Dibelius resurrected a word that hadn’t been in use for 1,500 years. But can that be true? Well, it would appear the Mark Goodacre thinks so. In a post from back in 2013 he recommends we abandon the term, for several reasons, and concludes:

In any case, what was ever wrong about talking about “passages” in the first place? The word “pericope” is in any case a legacy of the kind of form-critical approach to the Gospels that we have all long-since abandoned. Austin Farrer so disliked that kind of atomistic approach that he used to talk about “paragraph criticism”, noting that he was quite happy to look at isolated paragraphs but that, in the end, it was the Gospel as a whole that rewarded careful, critical study. (emphasis mine)

I recognize “legacy” as a euphemism for inferior, out-of-date, and just plain bad. In my own line of work, we sometimes refer to legacy source code and legacy operating systems for stuff that hangs around that we wish we could get rid of, but won’t go away. And while I may have not abandoned form criticism, I don’t imagine for a minute that Goodacre’s “we” would ever include the likes of me.

Chopping Up the Gospels

As far as an atomistic approach, that’s a derogatory way of explaining what Jacob Bronowski called the analytical approach. Is it now considered “wrong” to take things apart to see how they work? And, while we’re at it, who in the first place decided to take the gospels apart in order to see how they were assembled?

We have already seen that the Memory Mavens detest the atomistic approach to the gospels. And they naturally blame the form critics for taking us down the wrong path for far too many decades. As Chris Keith put it in his concluding essay for the book, Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity:

This general method thus requires an initial big-picture approach to the historical Jesus by including all available sources and socio-historical factors in a given theory. It also stands in stark contrast to the atomistic approach of the criteria of authenticity, wherein only those traditions deemed “authentic” factor into a theory of the historical Jesus. (p. 202, emphasis mine)

Keith and his friends lump form criticism in with the criteria for authenticity and the abhorrent practice of chopping the gospels up into little bits (pericopes or percopae). They encourage us to look at the gospels as narrative wholes.

Having read several works on source criticism and the synoptic gospels, I know the form critics didn’t simply pluck the word pericope out of thin air nor did they collude with one another to pay some sort of homage to Jerome. It was in common practice and usage among the clergy and biblical scholarship for decades, if not centuries before Bultmann appeared on the scene.

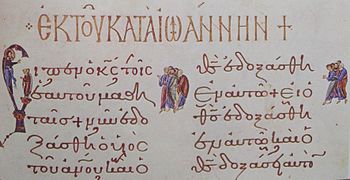

Griesbach’s Synopsis

Earlier works surely exist, but I’ve decided the best example for my purposes comes from the 18th-century German scholar, Johann Jakob Griesbach. Most of you will recognize the name from the Griesbach Hypothesis, which states that Matthew was the first written gospel and that Mark is a summary of Matthew and Luke. But he’s also famous for his synopses of the gospels. As you may recall, the synopsis he published in 1779 was called Synopsis evangeliorum Matthaei, Marci et Lucae cum Parallelis Joannis Pericopis (A Synopsis of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke with Parallel Johannine Pericopes).

One early result of Griesbach’s exercise in trying to place the gospels in parallel columns was the clear, observable fact that Matthew’s and Mark’s chronology just don’t line up. By the third printing, Griesbach himself wrote:

I have serious doubts that a harmonious narrative can be put together from the books of the evangelists, one that adequately agrees with the truth in respect of the chronological arrangement of the pericopes [chronologicam pericoparum dispositionem] and which stands on a solid basis. For what [is to be done], if none of the Evangelists followed chronological order exactly everywhere and if there are not enough indications from which could be deduced which one departed from the chronological order and in what places? Well, I confess to this heresy! (p. 27, Greeven, 1978, emphasis mine)

The very act of trying to line up the three Synoptics against one another proved to Griesbach that he could not create a true harmony of the gospels. In fact, he resisted convention and did not try to paper over discrepancies. And to his credit, although his name would eventually become synonymous with the theory that Matthew wrote first, his synopsis does not inherently favor any particular solution to the synoptic problem. The reader may follow any gospel, all the way through, vertically, and still see the corresponding pericopes (if they exist) in the other gospels horizontally.

If you study arguments according to the order of the gospels, you’ll no doubt use parallel gospels, synopses, not too dissimilar from Griesbach’s. But if you argue that Mark (or Matthew) came first because of your analysis of order, exactly what are we talking about? The order of what? Farrer’s paragraphs? No, we’re talking about discrete stories whose particular order within each gospel depended upon the purpose of each evangelist.

A word that never fell out of use

In fact, if you search using Google books, looking for the word in its various spellings — percope, pericopi, perikope, etc. — you’ll find it in use continually from the middle ages to the modern period. From early times, the church used the word to refer to the readings of individual stories in lectionaries. Later, as we noted above, source critics who studied, for example, the synoptic problem and the tradition history of John’s gospel, used the word to describe discrete stories in the gospels.

And yet the fact that the form critics also used the term has somehow now made it taboo in some quarters. Why?

The creativity of early Christian communities

We can find a clue in Bishop Timothy Whitaker’s 2014 online review of Richard Bauckham’s Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. His introduction is quite telling, especially this part:

Most kinds of historical Biblical criticism such as source criticism, redaction criticism, and literary criticism do not necessarily challenge the traditional view of the Gospels. The case is different with Formgeschichte or “form criticism,” which is a kind of historical Biblical criticism developed by German New Testament scholars in the early twentieth century, notably Karl Ludwig Schmidt, Martin Dibelius, and Rudolf Bultmann. . . . The form critics proposed that these “forms” were transmitted over a long period of time in anonymous Christian communities in which they were creatively adapted to the needs of the communities. The impression is created by the form critics’ theory of the oral phase of the transmission of the traditions about Jesus that the Gospels tell us more about the early Christian communities than they do about Jesus. Formgeschichte, which literally means “form history,” does indeed challenge the premise that the Gospels were written to preserve the memory of Jesus’ life by eyewitnesses. (emphasis mine)

It’s all well and good if you want to study the gospels scientifically from the perspective of genre, narration, source, redaction, rhetoric, even “memory.” There is one tree in the garden from which we may not eat. It sounds a bit extreme, but Bishop Whitaker is right; form criticism is different. Not only does it tell us that the stories in the gospels were “creatively adapted,” as he rightly says, but it also shows that they were often invented out of whole cloth.

Rabid bias

That insight has made form criticism persona non grata in the reactionary religious environment of Anglo-American biblical studies. Just how much do they hate Formgeschichte? Enough to dump a word Christians have been using for centuries. Enough to claim that form criticism has been universally abandoned. Enough to pretend that its practitioners excluded all other kinds of criticism — that they ignored everything else.

The rabid bias against form criticism has unfortunately blinded our friends, the Memory Mavens. In a rational world, the biblical scholars who are well-versed in social memory and its related phenomena would by now have had an epiphany. Bultmann explained that the needs of early Christian communities caused them to embellish and to create stories, while Halbwachs explained how groups created memories to serve the needs of the present.

However, they discard the explanatory power of social memory, conflating it instead with human recollection (personal memory). They spend so much time distancing themselves from the form critics you can hardly blame me for wondering if they do protest too much.

Tim Widowfield

Latest posts by Tim Widowfield (see all)

- What Did Marx Say Was the Cause of the American Civil War? (Part 1) - 2024-05-12 19:09:26 GMT+0000

- How Did Scholars View the Gospels During the “First Quest”? (Part 1) - 2024-01-04 00:17:10 GMT+0000

- The Memory Mavens, Part 14: Halbwachs and the Pilgrim of Bordeaux - 2023-08-17 20:39:42 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

This seems mostly right. By the way, the forms I think, were often borrowed from much earlier rituals, from other religions and secular practices. Like coronation ceremonies and so forth. Since this links Christianity to earlier, non-Christian rituals, this finding was disliked by evangelicals. Though the idea is supported by the social sciences, including comparative anthropology.

To be sure, formalism implies Chistianity is not unique. Indeed, the very word “Christ” probably came from the near cultural universal of publicly marking certain people as official leaders, by anointing or christening them.

There are certainly problems with many Criteria. But I agree that an attack on specifically formalism does not help. Partially since the attack is really emotional, evangelical/apologetic in nature.

How’s this for a postulation, Bee?

If there is borrowing from earlier rituals or other religions…how would it be different from Philo trying to mesh the OT with Greek philosophy, eg Plato and Aristotle?

Separately and on the pericope topic: Interesting thing about pericopes…they can be made to fit a liturgical year.

Similar way to the Memar Marqe being a LITURGICAL document.

Markan pericopes and Memar Marqe would definitely be related if the DATING of Memar Marqe was put properly back to the first century instead of the fourth.

It IS amazing that because some researchers put him in the fourth, nobody is yet connecting the Samaritan Mark to any other Mark.

These are important concerns. I agree that Philo and others bringing Greek ideas into Judaism, is part of the same picture, that would include ritualists, priests, adding their rituals to any nascent Christianity.

Here I’d add that normally this priestification is seen as indeed, a later development, by the emerging bureaucracy of the Church, 4th century. Here however I might note with Von Rad and the History of Religions school and anthropology, that ritualistic forms existed long before 1AD. And even before Judaism.

So for that matter, these priestly formulas could be in on the formation of Chrstianity, right from the start. And even before.

Could Christianity have been therefore largely a priestly invention? Did Jesus invent the liturgy. Or did the liturgy invent Jesus?

Standard rituals, roles, had their own relatively independent, formative energy. Lately, even Hurtado seems willing to consider that a very general, ritually-defined role like a Christ or a “Lord,” might be a major part of the constituent makeup of Jesus.

So was Jesus an empty suit? Given all the emphasis on white linen, and his too-good look, maybe the clothes made the man, rather than vice versa.

Jesus often looks too good to be true. As if someone made up a character, to illustrate a preconceived ideal or idea.

Bee, I’ve pretty much come to that conclusion myself…which is quite a step for me, as I have been brought up Christian and it was NOT the easiest step to say: “Jesus is Superman…requires the same SUSPENSION of Disbelief.”

But I’ve been able to change beliefs and opinions to suit facts.

There really is NO archaeology or independent literature OF that century that really can back a real Jesus.

The key joke of this is…Philo doesn’t even mention him. Which is strange, considering Philo wrote all the stuff we’d tentatively consider Christian.

If he’s made up…I can only work with known REAL historical figures.

I’m already at the point “historical” Jesus is something I said bye-bye to already.

And I’m even taking the word of a Pagan, LUCIAN, over early church fathers. Doesn’t mean I’d take up paganry…just have to accept there’s a HUGE difference between a belief and a reality.

I trust the Romans and their histories to be far more rational and reliable than their far less advanced subjects, like the Christians.

In the case of Philo, I see him as a somewhat rational, hellenized, platonistic, romanized Jewish citizen. Whose ideas on a son of God were expanded by locals, to help invent their Christianity.

Philo is not evidence that an early Christianity existed. But the opposite. That Christianity was invented out of a misunderstanding of earlier and contemporary figures. Like Philo. And his writings on say a son of God. A common Roman idea.

I think form criticism is alive and well. Ehrman in “Did Jesus Exist?” points out the myriad of place Matthew’s Jesus imitates Moses (DJE, 198-199). Ehrman says “In point after point, Matthew stresses the close parallels between the life of Jesus and the life of Moses (DJE, 199).”

How does that relate to form criticism?

Ehrman says:

“So far as I know, there are no longer any form critics among us who agree with the precise formulations of Schmidt, Dibelius, and Bultmann, the pioneers in this field. But the most basic idea behind their approach is still widely shared, namely, that before the Gospels came to be written, and before the sources that lie behind the Gospels were themselves produced, oral traditions about Jesus circulated, and as the stories about Jesus were told and retold, they changed their form and some stories came to be made up (Ehrman, DJE, 85)

-On the relationship between haggadic midrash and form criticism, see Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist, 185-186

I think maybe it’s time for a remedial form criticism post. Ehrman is stuck on that old “telephone game” idea, which focuses on gradual changes in transmission. “They changed their form” doesn’t cut it.

Yes please on remedial form criticism post!

Oral tradition is a non-starter. We are lucky to have what little written material has survived.

Yes, please. I am now extremely confused because, according to Brodie (I looked it up), a centerpiece of form criticism is oral tradition. See The Birthing of the New Testament at p. 51. From that perspective, I don’t see how form criticism is of much use as it is not falsifiable. What are we fighting for here?

There are lots of forms, including oral storytelling genres, and verbal formulas. But these forms in turn are part of cultural rituals. Like the standard words issued in tribal initiation ceremonies. So behind many oral forms, are cultural forms, rituals.

But the question is, how much of what is reported of the past was distorted – or even created – by these ancient cultural forms or stereotypes.

So if we see a form in a Jesus speech, this might mean that an earlier real Jesus was having his words forced into standard cultural molds. But for that matter, maybe the demand for forms was primary. And people would pray to the forms, really. To the general notion of a “Lord” say. And even then plug almost any name, real or fictional, into that general model.

Peoples had believed in say ” gods” and “Lord”s long before Jesus. So much of what Jesus was, existed in the culture before he is said to have existed.

In other words, Jesus might be a simple product of myths. Or related to that, cultural stereotypes. Or forms. The name Jesus was just one, perhaps fictional, plug in. To an earlier system of standard beliefs, rituals, forms. And finally it was those forms that created the legend. Rather than vice versa.

“That insight has made form criticism persona non grata in the reactionary religious environment of Anglo-American biblical studies.”

Are you thinking about a specific segment of people within New Testament studies? I haven’t seen that kind of aversion in OT studies, and we have NT folks like Thomas Brodie who rely on form criticism extensively.

Are you sure about Brodie?

Brodies relies extensively on form criticism: seeing how New Testament stories are shaped and formed according to the form of the Old Testament story that they are immitating – see Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist, 185-186.

Alas, no. I’m not sure about your view, either. See above.

A tangent for Tim.

Jacob Bronowski

I remember his landmark BBC TV series “The Ascent of Man” well. Or at least I think I do.

So last week I’m in the ABC Shop [Oz version of the BBC] and there is a set of DVDs of ‘The Ascent of Man”. grabbed it gleefully.

Haven’t watched it yet.

And then yesterday I’m in my local regional library and there is a copy of the book of the series.

Grabbed that too.

And raed the first 2 chapters last night – hasn’t aged well at all. I hope it improves back up to the standard I recall.