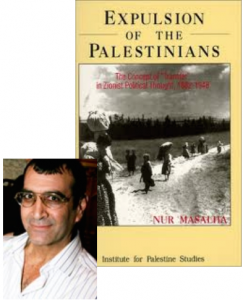

Continuing the series from Nur Masalha’s Expulsion of the Palestinians. . . .

Continuing the series from Nur Masalha’s Expulsion of the Palestinians. . . .

One bible myth stands out today as bearing a major responsibility for modern wars, ethnic cleansing, and ongoing bloodshed. That myth is that a modern race has a right to the land of Palestine by virtue of a history found in the Bible.

This series of posts has not examined that biblical myth itself (nor wider public receptions and political influence of the myth) but it has been exposing another myth that has ridden on the back of the first, the myth that the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is ultimately the result of Palestinians failing to respect the right and necessity of the Jewish people to settle in peace alongside them. This secondary myth is actually a recasting of the biblical myth of the hostile Canaanites proving to be the ungodly thorn in the side of the people to whom God had given the land. The new settlers, the myth relates, are for most part innocently seeking only a safe refuge in their historic homeland but have been met with unjustified hostility by the existing inhabitants. The impetus for the new settlement came with the revelation that an attempt had been made to wipe out the entire Jewish people in Europe and the survivors and their descendants only wanted a small piece of historical real-estate alongside a hospitable fellow-semitic race.

To support this additional myth another must be sustained: that one race is responding in bad or immature character (as we would expect of biblical Canaanites) while the other is fundamentally decent and caring (as we would expect….). And many of our news sources filter the story through these mythical constructs.

That is all part of the secondary myth.

The reality, as these posts have been demonstrating on the basis of Israeli records, is otherwise.

The modern state of Israel was founded upon an ideology, a belief, an expectation among its key leadership that the Palestinian Arab population would have to be expelled from their long-held homes and lands. This belief among Zionism’s founding fathers that the state of Israel would require the removal of the bulk of Arabs from Palestine preceded World War 2, preceded the Holocaust, and made possible the forcible expulsion of thousands of Palestinians at Israel’s founding in 1948. The difference that the Holocaust made to the argument for Israel’s founding was that it facilitated international support for the new Jewish state. Popular sympathy for the horrors suffered by the Jews in Europe blinded many to the injustices being foisted upon the traditional inhabitants of Palestine.

There are many other secondary myths that serve to support the above myths. Among these are myths about the events that precipitated the flight of many Palestinians in 1948 and the respective views and actions of the governments involved in that war and subsequent wars. I will address these, too, and again on the basis of Israel’s archives, and in particular through the works of Jewish historians sympathetic to Israel.

In May this year Israel’s Deputy Foreign Minister Tzipi Hotovely addressed foreign ministry staff in Jerusalem and 106 Israeli missions overseas by video link, and declared:

This entire land is ours. All of it, from the [Mediterranean] Sea to the [Jordan] River, and we are not here to apologise for this. . . .

She afterwards added:

We expect as a matter of principle the international community to recognise Israel’s right to build homes for Jews in their homeland everywhere.

The Telegraph‘s correspondent Brian Tait noted that her speech was

laced . . . with biblical commentaries in which God promised the land of Israel to the Jews.

Hotovely, as we have seen, merely expressed what has been the conventional thinking and beliefs of most of Israel’s founding fathers from the very beginnings of the nation. As we have also seen, the same figures have found it more politic at times to not be so open with Western media about such sentiments.

The situation so far

The previous post brought us up to August 1938 with the British government finally deciding not to support immediate hopes of Zionists for a Jewish state in a partitioned Palestine.

Problems:

- It was clear to the British government from the Arab reaction that the recommended population transfers for even a two-state solution could not be carried out without violence and injustice to the livelihoods and deeply rooted feelings of the local population;

- Without a state of any kind the Zionists understood that there was no way to effect a transfer of Palestinians at all.

The British therefore:

- Decided it was time to slow the pace of their support for a Jewish state until they took time to consider seriously the Arab grievances;

- Called for a general conference on Palestine to consist of Arab, Palestinian and Zionist representatives — due to be held in London in February-March 1939.

The Zionist leaders therefore:

- Continued to press the British government for more liberal Jewish immigration into Palestine;

- Continued to lobby for more freedom to to purchase land from Arab landowners;

- Judged it prudent to avoid embarrassing the British government with further public calls for the transfer of the indigenous Arab population.

It was clear that the British were not going to risk antagonizing the Arabs at a time when the clouds of war were rising.

The Jewish Agency therefore turned its attention towards that other promising power and potential supporter, the United States.

Ben Gurion’s memorandum

Continue reading “Expulsion of the Palestinians: Caution and Discretion during the War Years”