Previous posts in this series looking at Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us by Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko:

Previous posts in this series looking at Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us by Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko:

- How Terrorists Are Made: 1 – Personal Grievance

- How Terrorists Are Made: 2 – Group Grievance

- How Terrorists Are Made: 3 – Slippery Slope

A number of critics who are more interested in attacking religion, especially Islam, than in making the effort to understand what scholarly research has uncovered about why individuals become terrorists have often missed a critical reason for radicalization. This reason seems too simple and some have scoffed at the idea as if it is some left-wing loony nonsense — such as anthropologist Scott Atran’s claim that street soccer networks can enable us to predict who is at risk of extremism. It is a fact, however, that some of us over time do get mixed up in things neither we nor any of our acquaintances would ever have suspected. And it’s not because we convert to some fanatical religious idea.

McCauley and Moskalenko introduce us to Sophia (Sonia) Perovskaya, a Russian girl born into nobility and who was attracted to idealistic student movements seeking to improve the lot of the peasantry. Her ideals forbade her from crossing the line of violence.

Like many others who ventured “into the people,” Sonia did not have much success in mobilizing the peasants. Instead, it appears from her letters at the time that she became more and more involved in the mission of making peasants’ lives better, having seen the horrible conditions in which they lived.

Failure to politicize the peasants led a fellow revolutionary, Andrei Zhelyabov (we met him in the first post of this series), to persuade a few that violence was the only answer. The peasants were too besotted with the Czar; kill the Czar and they would be forced to engage in actions for a better society. Sophia’s response was absolute refusal:

“revolutionaries must not consider themselves above the laws of humanity. Our exceptional position should not cloud our heads. First and foremost we are humans.”

Unfortunately there was a strong sexual attraction between Andrei Zhelyabov and Sophia Perovskaya and Sophia found herself contributing her time to both the main nonviolent group and the breakaways and she ended her life on the gallows with Andrei for her part in the attempted assassination.

The above is just one case study that in one form or another has been repeated many times.

The prevalence of friends, lovers, and relatives among those recruited to terrorism has made personal relationships an important part of recent theorizing about terrorism, perhaps because it recovers the “known associates” approach to criminal investigation. As with criminal gangs, individuals are recruited to a terrorist group via personal connections with existing members. No terrorist wants to try to recruit someone who might betray the terrorists to the authorities. In practice, this means recruiting from the network of friends, lovers, and family. Trust may determine the network within which radicals and terrorists recruit, but love often determines who will join.

A Red Brigade member explained his motivations:

There are many things I cannot explain by analyzing the political situation . . . as far as I am concerned it was up to emotional feelings, or passions for the people I shared my life with.

Political scientist Donatella della Porta refers to research on German militants and the Red Army Faction:

“There is widespread agreement among researchers that ‘most terrorists . . . ultimately became members of [German] terrorist organizations through personal connections with people or relatives associated with appropriate political initiatives, communes, self-supporting organizations, or committees — the number of couples and brothers and sisters was astonishingly high.”

Della Porta refers to “block recruitments”, meaning that a group of friends would all decide together to actively join an underground movement. Once in the group, the adventures experienced, the threats and dangers encountered, all work towards increasing any individual’s bond with their comrades. The sense of solidarity works both to encourage entry into the group and to prevent any serious thought of leaving the group.

An Irish Sinn Fein member is quoted:

“There’s times I’ve said to myself, ‘Why? You’re mad in the head, like.’ But . . . I just can’t turn my back on it. . . . there’s too many of my friends in jail, there’s too many of my mates given their lives, and I’ve walked behind — I’ve walked behind too many funerals to turn my back on it now.”

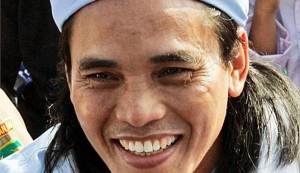

Australians more than many other Westerners are familiar with Amrozi “the smiling terrorist”, the Indonesian who bought the van involved in the Bali bombings (not far from where I am typing this post) in 2002. Amrozi bin Nurhasyim is described as “a spectacular failure of his father’s efforts” to raise him as a devout Wahabbist Muslim.

He was a fun-loving disgrace to his whole family.

He drifted through schools, jobs and marriages, always making himself useful as the one who could fix anything from a motorbike to a cell phone.

His older brother, on the other hand, Muklas, did take up his father’s Islamist teachings. Muklas became a leader in a terrorist outfit with ties to Al Qaeda, operated often in Malaysia to escape the Indonesian authorities, had experienced the war in Afghanistan, and had been tasked with building a new Islamist boarding school for Indonesians living in Malaysia.

After drifting through odd jobs and a couple of marriages Amrozi finally caught up with his older brother to whom he looked up as a most admirable success and role-model in life.

Amrozi did not adopt a radical version of Islam because he was intellectually persuaded, and did not join in violence against infidels and apostates because he had suffered himself from those targeted. He joined in the life and work of the brother he admired in order to be with his brother, and he basked in brotherly approval when he later joined Muklas and their youngest brother, Ali Imron, in the campaign of terrorism that produced the Bali attacks.

Here is Sally Neighbor’s summary of Amrozi’s path to terrorism:

‘It was Mas [brother] Muklas who raised my awareness to fight the injustice toward Islam.’ The effort that went into Amrozi’s transformation would prompt Muklas to boast with a chuckle: ‘Thank God, with endless patience, bit by bit, to this day, he’s also in the league of praiseworthy terrorists.’

To complete the network, Amrozi bought the incriminating van from a personal acquaintance. He was executed alongside his older brother in 2008, proud of what he had finally achieved in life.

.

All quotations are from the Kindle version of Friction.

Incidentally — in preparing this post I learned that Australia’s “Father of Federation”, Henry Parkes, wrote a poem about Sophia Perovskaya, The Beauteous Terrorist. He was struck by the incongruity of her outward appearance and character housing the soul of a murderer, apparently unaware of her life story prior to her involvement with the assassination attempt and of how she had changed through her love for Zhelyabov.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

This may have already been addressed in one of the previous threads. ISIL recruitment through the internet seems to be relatively unconnected to traditional approaches? Yes, no? Is such recruitment more influenced by religious persuasions? Also, ISIL is probably best understood as a quasi-state and recruitment is perhaps affected somewhat differently. We hear much about the caliphate in relation to ISIL recruitment and I wonder how much this truly affects decisions.

The most comprehensive discussion of your question that I have read is in chapters 6 and 7 of Stern and Berger’s book that I recently posted about.

Chapter 6 is titled “Jihad Goes Social” — covers the various extremist platforms used, Youtube, Google, Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter and others — the various ways law enforcement authorities approach these venues; the line between hard-core (secret) terrorist accounts and those accessible to those at initial inquiry stages, etc.

Chapter 7 is “The Electronic Brigades”: Yes, ISIS is making strategic use of web social media for its recruiting and propaganda. ISIS has engaged with more active, dedicated and organized use of this media than its rival groups have. Here’s one small snippet (reformatted):

It appears to me that the social media technology has made it easier for individuals to be connected to new networks and therefore prised away from their off-line ones. The networks and relationships are there — with the difference that everyone has more opportunities for exposure to more of them. It’s a fascinating question.

In response to another part of your question, the same book (Stern and Berger) cite an interview with Thomas Hegghammer, director of terrorism research in Norway. The original online article is Why Have a Record Number of Westerners Joined the Islamic State?.

He does say that a higher ratio of the foreign fighters (we can assume to a large extent recruited online) are more ideological than many others. Earlier recruits had more altruistic motives (removing Assad from the power over the Syrians). But as we would expect many are also attracted by the adventure.

Simplistic explanations — it is religion, it is political grievance — break down when we try to explain why, say, only one of a pair of siblings brought up and living together will radicalize.

For some reason, Mr.Godfrey mindlessly parrots Sam Harris’s claim that I think that religion has no role in jihadi violence. Instead of Parroting, I suggest he read the articles of have written lately on the subject in Science, PNAS, The New York Times, Guardian, Daily Beast, as well as interviews in Nature on NPR, Fox, MSNBC and elsewhere.

Scott, I regularly refer to your writings, both books and articles, with strong approval and I regularly condemn Sam Harris’s distortions accusing you and others of denying any role for religion in jihadi violence.

In the comment to which you took exception I was actually referring to Sam Harris’s and Jerry Coyne’s ignorant mocking of your “soccer associations” having any predictive value regarding who was likely to become a terrorist. This particular post was zeroing in on the theme of social networks and bonding as one of the factors involved in radicalisation.

Regular readers of this blog know I am on your side and totally against Sam Harris’s. See http://vridar.org/category/book-reviews-notes/atran-talking-to-the-enemy/ for example.

AH, I misunderstood, shame on me, and I apologize.