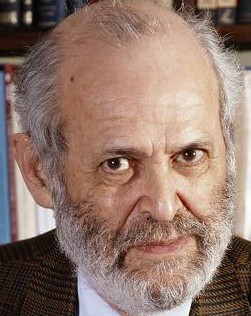

Some scholars today say a major work of Geza Vermes first published in 1973, Jesus the Jew: a historian’s reading of the Gospels, has “stood the test of time”. From my own recollection of Vermes’ book I don’t think that is necessarily a good thing.

Here are some of the more recent accolades:

Indeed, some of Vermes’s distinctive contributions have been extremely influential and so far stood the test of time. In addition to the general view of Jesus the Jew, placing Jesus in the same category of charismatic Jewish holy men such as Hanina ben Dosa has proven to be particularly popular and the overall thesis has not been refuted, even if various details have been challenged. (See earlier post on Why Christianity Happened, p. 29. My bolding and formatting in all quotations)

Chris Keith cites Crossley approvingly:

[James Crossley’s] lecture emphasized two other things for me as well. First, the work of really appreciating and articulating the influence of Vermes’s 1973 Jesus the Jew is perhaps still only starting. Obviously, most people in historical Jesus studies know that Vermes’s study was important, even a watershed. But I have heard several lectures here lately where scholars are emphasizing just how revolutionary it was. This position is not just because of Vermes’s emphasis on seeing Jesus against a Jewish background, which deservedly gets attention, but also for his noted dislike of structured “methodology.”

Let’s see what happens when Vermes discards “structured methodology” in relation to just one of the points, though a key one, in Jesus the Jew.

Placing Jesus in the same category of Jewish holy men

We see above Crossley singling out Vermes placing Jesus in the category of charismatic Jewish holy men like Hanina ben Dosa. Let’s look at Vermes’s justification for this.

We see above Crossley singling out Vermes placing Jesus in the category of charismatic Jewish holy men like Hanina ben Dosa. Let’s look at Vermes’s justification for this.

(Note: I cannot in this one post cover all of the details and nuances of Vermes’s argument. I touch only on key points. Anyone who has read Jesus the Jew may well raise some objections to specific points I make here. I believe my points can withstand more extensive discussion but please note that I would not want anyone quoting what follows as my “final word”. Take what follows as my tentative disagreements with Vermes’ interpretation of the evidence.)

The term “charismatic” is used because Jesus is said to have drawn upon “immediate contact with God” for his supernatural abilities. While Vermes tells us that such individuals were found throughout “an age-old prophetic religious line” he does not, from what I can recall, offer evidence for this age-old line. In fact, he seems to me to be forcing the evidence associated with two names to provide proof of the existence of this “line” in the time of Jesus.

Hanina ben Dosa

Vermes tells us that Hanina ben Dosa was

one of the most important figures for the understanding of the charismatic stream [of Judaism] in the first century AD.

In a minor key, he offers remarkable similarities with Jesus, so much so that it is curious, to say the least, that traditions relating to him have been so little utilized in New Testament scholarship. (p. 72)

The sources are from the later rabbinic writings. These tell us that he lived near Sepphoris, a major city otherwise noted as situated close by Nazareth.

I enjoy reading and learning new things. So my first question here was to ask how we know this Hanina ben Dosa lived at this time and place.

That Hanina lived in the first century AD may be deduced indirectly but convincingly from the fact that the Talmudic sources associate him with three historical figures who definitely belonged to that period: Nehuniah, a Temple official, Rabban Gamaliel and Yohanan ben Zakkai . . . (p. 73)

Vermes adds a footnote here:

A. Büchler, Types of Jewish-Palestinian Piety, p. 87, and H. Danby, The Mishnah (… 1933), p. 799, assert that Haninah flourished after AD 70. However, if J. Neusner’s dating of Yohanan ben Zakkai’s Galilean period to before AD 45 is accepted (cf. A Life of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, p. 47), and the teacher-pupil relationship between him and Hanina assumed, the latter’s birth might conjecturally be placed around AD 20. . . . (p. 241 — The links I have added are to online editions of the books to enable anyone interested to study the arguments and their evidence for themselves.)

So Hanina ben Dosa was a younger contemporary of Jesus. Perhaps.

Okay, let’s for the sake of argument assume we have carefully read the details of Büchler, Danby and Neusner’s respective arguments, followed up additional reading about the sources they discuss, and have concluded without any doubts at all that Neusner has given scholarship the categorically correct time and place of this person for all time. What sorts of things did this Hanina ben Dosa do that made him so like Jesus?

Hanina [is] a man of extraordinary devotion and miraculous healing talents.

As for devotion, it was said that he would spend an hour setting his heart pure before God before starting his prayer. If a king greeted him while praying, he would not hear; if a poisonous snake coiled around his leg and bit him he would not falter.

Now I can’t imagine anyone doubting the piety of Jesus but there’s a big But here. The piety of Jesus is of the same kind we find expressed throughout the Jewish scriptures. Nowhere in those scriptures, or in any of the stories of Jesus, do we encounter the sort of self-punishing body-denial and asceticism that we see here associated with Hanina ben Dosa. Hanina’s self-flagellating endurance and focus that reads to me much more like the later performances of the desert monks who would “prove” their piety by means of similar ordeals of endurance.

The kind of piety demonstrated by Hanina ben Dosa is not like the quietly assumed inner-spirit piety of Jesus. Jesus did not require long spells of bodily preparation before his “spirit power kicked in” and proved itself with ostentatious wonders of denial and endurance. My first thought is that we are looking at two different cultural contexts here. One from Temple or Second Temple era Judaism and one from a later time-frame of fanatical hermits, ascetics, holy men and monks. I know of no comparable Jewish asceticism prior to the demise of the Second Temple and the rise of the rabbinic era.

What of his healing prowess?

Again we run into awkward questions. At least they are awkward for me.

Here’s an example. The community elder and Hanina’s teacher, Yohanan ben Zakkai, was at the point of death, when a father appealed to Hanina:

‘Hanina, my son, pray for him that he may live.’ He put his head between his knees and prayed; and he lived. (bBer. 34b)

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it. Vermes reminds us of the source of this image:

Elijah climbed to the top of Carmel, bent down to the ground and put his face between his knees. (1 Kings 18:42, NIV)

This was how Elijah prayed his legendary prayer for rain. The author is emulating the Elijah trope (or on this particular occasion Hanina decided to pretend to pray like Elijah even though Elijah never prayed like this for healing).

Jesus is a contrast, not a comparison, to the exercise of this sort of prayer. Jesus did not really pray to God to heal anybody but rather commanded them to be healed. The evangelists don’t emulate Elijah. They transvalue him. Jesus is more akin to a god who heals from heaven, like Ishtar or Nabu, or like Yahweh.

I can see competing literary models at work here. I can see little reason to conclude that the two persons of interest belong to the same guild. There are two possible exceptions. Jesus does on one instance use saliva, but still he does not pray, and the use of the saliva can well be interpreted as a literary device to break the healing into two parts in order to conform to the surrounding context of symbolic double actions. Hanina on one occasion does pray for a young boy to be healed from a distance and this surely does remind us of Jesus performing a similar miracle. But again Hanina is limited by the need to pray, and by this he knows if his prayer has been answered:

If my prayer is fluent in my mouth, I know that he (the sick man) is favoured; if not, I know that it (the disease) is fatal.

The authors have created two quite different types of healers. One is god in flesh (at least according to the myth or “christology” of the author), the other is seen as another Elijah and in an age when godliness was proved by one’s ability to wilfully suffer (not simply suffering as a consequence for obedience).

If so far I have considered the similarities between Jesus and Hanina ben Dosa are less than truly “remarkable” then what of other points of similarity Vermes identifies? These include

- apparent hostility from the authorities

- a life of extreme poverty

- a rejection of cultic rituals

The hostility in Hanina’s case at no point comes close to murderous hostility. At worst there are mild expressions of envy. But envy is an ages-long trope that is almost always related to holy ones. Recall Abel, Joseph, Moses, David, and so on.

Poverty and simplicity of worship are also common motifs for holy men in all ages. Besides, we cannot forget that Jesus is said to have commanded those he healed to perform sacrifices and there are also indications that his followers did assist him with fine clothes and precious anointing oils.

Honi the Circle-Drawer (the Mishnah) / Onias the Righteous (Josephus)

This charismatic known from both Josephus and the later rabbinic writings was known to have lived around the mid-first century BCE, certainly before Pompey’s conquest of Judea in 63 CE. That is, around a century before Hanina ben Dosa.

This charismatic known from both Josephus and the later rabbinic writings was known to have lived around the mid-first century BCE, certainly before Pompey’s conquest of Judea in 63 CE. That is, around a century before Hanina ben Dosa.

We have less detail about Honi than for Hanina. Here’s the moment for which he is noted from the Mishnah (from the Josephus.org site):

Once they said to Honi the Circle-Drawer, “Pray that rain may fall.” . . . .

He prayed, but the rain did not fall. What did he do? He drew a circle and stood within it and said before God, “O Lord of the world, your children have turned their faces to me, for I am like a son of the house before you. I swear by your great name that I will not stir from here until you have pity on your children.”

Rain began falling drop by drop. He said, “Not for such rain have I prayed, but for rain that will fill the cisterns, pits, and caverns.”

It began to rain with violence. He said, “Not for such rain have I prayed, but for rain of goodwill, blessing, and graciousness.”

Then it rained in moderation.

Again, I don’t think hyper-scepticism is the reason I fail to see “remarkable similarities with Jesus”.

Vermes comments on Honi’s attitude towards God here. It appears to be decidedly irreverent, he says. Again, I confess I find myself in less than full agreement. Okay, if Honi is being a bit cheeky in his manner of addressing God it is because God here deserves it. God is behaving like a childish twit who deserves to some common sense knocked into him. Nonetheless, Vermes finds the same prophet, named Onias, redeemed with more reverence by Josephus. Instead of the ominous (magical?) circle-drawer epithet he is called “The Righteous”:

There was a certain Onias, who, being a righteous man and dear to God, had once in a rainless period prayed to God to end the drought, and God heard his prayer and sent rain.

The Mishnah passage where Honi draws the circle and orders God to send rain continues with an exchange in which the leading Pharisee says he would like to condemn Honi for his petulant manner of speaking to God but can’t deny that God indulges him like a spoiled child.

The only other time Onias is called upon to perform a miracle is during a civil war when one side demanded he pray to God to enable them to overrun a city they were besieging. Pressed to act Onias prayed instead that neither side would harm the other. Those trying to use his contact with God for their own ends thereupon stoned him to death. This was at Passover time. God punished them all with a violent crop-destroying wind.

Details in the Mishnah are not consistent. Some paint Honi as soberly righteous, others as a somewhat suspect character. I don’t know if Honi can truly be compared with the Jesus of the gospels at very many levels. He appears to me to be another adaptation of various biblical tales of Elijah and Balaam and a foil to deliver various theological points for rabbis.

Is it just me, or. . . ?

Others may differ. Some may see more to the similarities of both these persons with Jesus than I have indicated here.

I can’t help but sense that Geza Vermes is attempting to squeeze a foot into a shoe too small when he compares them with selected aspects of the life of Jesus. Where there are similarities they appear to me to be of the kind that are generic to all holy men and found throughout the literary tradition.

Nor do I see that the references to these two men, separated by a hundred years at least, clearly tell us that “a charismatic Jesus” was part of an “age-old tradition” of such holy men.

We need also to keep in mind the reason for the tales of Honi and Hanina being told as they were in the rabbinic writings. These were meeting the needs of the writers and their audiences as they were working out a new identity without cult and Temple just as the evangelists were doing something similar with Jesus in the Gospels.

What we could do, I suppose, to salvage a neat hypothesis, is to discard “structured methodology” and peel away Gospel elements that speak against Jesus being like Honi or Hanina and that way find the “real historical Jesus” was just like them after all.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

It has been many years since I read Vermes’ book, and like so many things in my past it’s now fuzzy in details, but does he have anything to say about (or to explain away) the fact that there is not the slightest piece of evidence in the entire body of NT epistles that their Jesus was ANYTHING on earth, let alone a charismatic holy man? They don’t even know that he was an earthbound teacher, since Paul says he (and sometimes others) get their goods directly from the spiritual Christ in heaven. (Surely he doesn’t try to use the acknowledged interpolation in 1 Thess. 2:15-16?)

Why is every scenario for the historical Jesus dependent entirely on the Gospels and the traditions originating with them, while the epistles are conveniently shunted aside and ignored? And what then is to prevent those Gospels (ultimately the first one written, Mark) from simply being fiction and allegory fashioned by the evangelists from the teacher/holy man TYPE prevalent in the world around them? The ‘individual’ spoken of and worshiped in the epistles lacks any such characterization or linkage with the individual in the Gospels.

Is Vermes’ even cognizant of that problematic anomaly? (Of course, neither is Ehrman or a host of other NT scholars.)

Earl Doherty

Vermes does not question the historicity of Jesus. This is assumed. Hence his focus on the gospels is intended to see what we can learn about that figure. I addressed the motivations/interests of Vermes in an earlier post, Good Bias, Hidden Bias and the Phantom of Jesus in Christian Origin Studies.

I originally intended to write a much more devastating (to my mind) criticism of Vermes’ whole approach to historical inquiry but opted for the soft option here because of the relevance of the supposedly charismatic Jewish holy man “tradition” to some scholarship and it was easier at the time to collate the data.

I still plan to do one more post on Vermes demonstrating just how “unstructured” anything that can be called “historical methodology” in his work is.

Earl,

I agree. I have been suspicious -while actively Christian and apostate- about the attempts to harmonize all those documents

when it is more likely that none of the original writers of those texts intended for their polemic to work in a larger system for

the purpose of theological orthodoxy, let alone liturgical forms like the Mass.

“Which Jesus” is a sound question as well as a fatal flaw in the idea of “Christian orthodoxy”.

I like what you say about “prevalent TYPE”.

In general to the post:

Just by the title “Jesus the Jew”, I will avoid reading this book; the idea of “Jew” itself is so equivocated, that applying another

contextually ambiguous word like “Jesus” to “Jew” as a descriptor, turns me off like a light.

Bible and religion scholars think their discipline and methodology are as rarified as advanced particle physics researchers,

but really they represent an overgrown book club; I have a high school diploma and a BFA, so that means I can read, write

and think about the Bible. Not only that, but I can find out what ‘scholars’ do by reading and thinking, and work out informed

opinions which may or may not be serious challenges to established axioms or paradigms.

Vermes probably has a lot to teach me, but that can be reciprocated; “Jesus the Jew”…well…what kind of “jew”?…which “Jesus”?

So, Neil, I don’t think that dealing with a significant point of Vermes’ argument regarding a “supposedly charismatic Jewish holy man ‘tradition’” is a “soft option”. Addressing one stated premise at a time slowly but surely leads toward the bigger elephant in the room, the Jesus historicity issue.

I haven’t read John R. Levison’s The Spirit in First Century Judaism, but after reading some of the following preview, particularly the sections entitled “The Spirit and Prophecy” (p. 244) and “The Spirit and Charismatic Exegesis” (p. 254), I’m inclined to think that the subject of a proposed specific “age-old prophetic religious line” needs a bit more clarification.

The Spirit in First Century Judaism preview

By the way, even though pages are missing in these sections, I see no reference to Hanina ben Dosa or Honi/Onias.

Vermes claimed to be very English in his methods – that despite his Hungarian origins the graft took. The caricature is that Germans go for grand overarching theories, the French for rationalism (even the language is ridiculously claimed to be rational), the Yankees for pragmatism and what works, the English for empiricism. Even more of a caricature the English are said to eschew method and by trial and error muddle through by intuition to truth.

I was once very attracted by Vermes’ books. As an atheist but inevitably, since brought up in a liberal Christian and post-Christian culture, finding some of the gospel stories very poignant, especially when viewed through humanist eyes, and because of my background from a poor family in a deprived part of England being sympathetic to the oppressed, I was naturally attracted at first to some kind of Ebionite narrative of Jesus. Vermes was very interesting and seemed to be able to sort out the genuine stories of Jesus from the spurious.

Vermes story is of a steady trajectory from a low to high Christology, from very Jewish to anti-Semitic. His Jesus is torah observant, sees gentiles as dogs and swine, but because of his father like love he feels from god can rise towards universality and can even, like Amos, bend the stick from ritual to mercy.

I suspect Vermes was a little conflicted between loyalty to Judaism and to sentimental Christianity. I may be wrong. I now believe there is little empirical or theoretical basis for his analyses. The charismatic Jews to whom he compares Jesus seem to be to be stories from the pietistic antizealot Pharisees who came after the destruction of the temple. The Jesus stories however begin as a world changing son of God.