This post continues from my earlier one that concluded with Mark W. G. Stibbe’s “very broad list of similarities” between Euripides’ Bacchae (a play about the god Dionysus) and the Gospel of John. Stibbe discusses these similarities in John As Storyteller: Narrative Criticism and the Fourth Gospel.

What Mark Stibbe is arguing

Stibbe makes it clear that he is not suggesting the evangelist

Stibbe makes it clear that he is not suggesting the evangelist

necessarily knew the Bacchae by heart and that he consciously set up a number of literary echoes with . . . that play (p. 137)

What he is suggesting is that

John unconsciously chose the mythos of tragedy when he set about rewriting his tradition about Jesus and that general echoes with Euripides’ story of Dionysus are therefore, in a sense, inevitable.

Stibbe firmly holds to the view that the Gospel of John is base on an historical Jesus and much of its content derives from some of the earliest traditions about that historical Jesus. The evangelist, he argues, was John the Elder, and he has derived his information from

- a Bethany Gospel (now lost) that was based on the eye-witness reminiscences of Lazarus, who was also the Beloved Disciple in the Gospel;

- a Signs Gospel (now lost);

- the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke)

His final chapter in John as Storyteller consists largely of a point by point argument that the events of the arrest, trial and crucifixion of Jesus in the Gospel are based on historical events.

At the same time, Mark Stibbe is arguing that the author, John the Elder, is constructing his supposedly historical source material in a quite literary manner. He has chosen to write about the life and death of Jesus as a tragedy, argues Stibbe, and this was quite a natural thing to do because, we are assured, Jesus’ life and death just happened to be acted out in real life like a tragedy. It was a natural fit.

That’s where Stibbe is coming from.

Mark Stibbe, a vicar of St Mark’s Church at Grenoside (Sheffield) and part-time lecturer in biblical studies at the University of Sheffield when he wrote this book, writes from the limited perspective of formal New Testament studies. So he writes from the viewpoint of a Christian studying why the Gospel of John wrote about the very real founder of his faith, Jesus, would echo aspects of a Greek tragedy.

What this post is questioning

I’m interested in a different perspective. A proper study of religion from a scientific perspective would be through anthropology, I would think. New Testament studies are primarily about analysing and deconstructing and reconstructing biblical or Christian myths. The end result must always be a new version of their myth, if we follow Claude Lévi-Strauss.

I last posted along this theme in 2011:

- Anthropologist spotlights the Bible and Biblical Studies

- Explaining (the Gospel) Myths — looking at how anthropology can set up a different perspective on the Bible.

- Messiahs, Midrash and Mythemes — more comparisons with the Gospels — in which I apply the anthropological perspective in the previous post to legends of births and deaths of messiahs.

- See also various posts relating to Philippe Wajdenbaum’s Argonauts of the Desert.

Since I began this new series I have found another who takes a similar perspective. Frank Zindler writes:

the study of religions — including Christianity — is properly a task for an anthropologist. (Bart Ehrman and the Quest of the Historical Jesus of Nazareth)

Anthropology would be the starting point. We’d also need to study comparative literature, mythology, religions and the societies of the era from which Christianity emerged. And we’d have to examine all of those through anthropological and sociological studies, too. Literature that appeared to be some sort of documentation of historical events would need to be tested against other studies and sustainable criteria, too.

So in this post I am more interested in examining whether it is fair to think that the portrayal of Jesus in the Gospel of John really incorporates another version of the myth of Dionysus.

The Gospel of John as a tragedy

Stibbe begins by comparing the Prologues of the Greek play about Dionysus, Bacchae, with the Gospel of John’s introduction. I quote here Stibbe’s translation (actually part paraphrase) of that Prologue. I will be extending Stibbe’s literary comparison into comparisons into the question of the relationship with the Dionysus myth itself.

I am Dionysus, the son of Zeus,

come back to Thebes, this land where I was born.

And here I stand, a god incognito,

disguised as man, beside the stream of Dirce

and the waters of Ismenus.

Like it or not, this city must learn its lesson:

Cadmus the king has abdicated,

leaving his throne and power to his grandson Pentheus;

who now revolts against divinity, in me:

thrusts me from his offerings; forgets my name

in his prayers. Therefore I shall prove to him

and every man in Thebes that I am god indeed.

(lines 1-2, 4-6, 39, 43-8)

Stibbe first of all points to the obvious differences:

- presupposition of a pantheon of deities vs two divine beings

- a deity of aggression and hedonism vs a divinity full of grace and truth

- a god speaking in the first person vs a narrator speaking about a deity,

- and so on . . . . .

(I’m don’t think Stibbe is quite accurate with his second point. In the play Dionysus several times tries to drum it into Pentheus’s head that his devotees are not, as Pentheus impiously suspects, hiding in the woods to engage in hedonistic sexual practices. But certainly the god of the play is a god of implacable vengeance against unbelievers.)

Then some (“very general”) similarities. Both texts are:

- poetic prologues

- centering on a divine being who assumed mortal flesh

- presenting the theme of revelation: each god will reveal himself to humanity

- complaints about the failure of the god’s own people to recognize and receive him

- praises of one man who did publicly recognized the deity (Cadmus and John the Baptist)

Following the Prologues, both narratives introduce the institutional powers (the king and the priests) that step in to block the purposes for which the deity has come. These powers, the king of Thebes and the Jewish leaders at Jerusalem, are blind to the truth of the god, ignorant, and they are stubbornly rebellious when confronted by him.

The very suggestion that Jesus is God’s Son is enough to drive the Jewish authorities into a frenzy of hate and determination to kill him. Jesus himself disappears when a crowd wants to make him king, only to be eventually tried and executed for that very charge.

Stibbe validly observes the way the gospel narrative sits well within “the essential mythos of tragedy”. John’s story is closer to Mark’s than the other Synoptics, and the Gospel of Mark has been thoroughly dissected and argued to be a form of tragedy. The liberated Gospel: a comparison of the Gospel of Mark and Greek tragedy by Gilbert G. Bilezikian is one work dedicated to arguing that Mark employs all the characteristics of Greek tragedy. Again, like Stibbe, Bilezikian assumes this was the most natural thing to do since Jesus’ real life was, coincidentally, lived just like a tragedy on stage.

Since he was obviously not motivated by pretensions to literary achievement, Mark cannot be accused of having deformed the material just for the sake of writing a story in the manner of Greek drama. It was the very nature of the story itself, with its quintessential concentration of all that is tragic about life, which called for the use of tragedy as a suitable armature for its orderly recording and preservation. (p. 141 of The Liberated Gospel.)

Was Jesus’ real life like a stage tragedy?

Both Bilezikian and Stibbe answer in the affirmative. Stibbe even says that it was “inevitable” that John’s story of Jesus (described as “the killing of a king”) should be written as a tragedy. Again on the same page he argues that even the echoes with Euripides’ Bacchae were “inevitable” (p. 137).

Yet his declarations of inevitability were nested within a paragraph in which he attempted to support his argument with reference to postmodernist historian Hayden White, and therein lies the problem for Stibbe’s own argument. Of White’s contribution to our understanding of how historians (implicitly including literary storytellers) write, Stibbe explains:

Hayden White has shown in his Metahistory that every historical reconstruction is fictive in form (not in content). In the writing of history, the historian — like the storyteller in literature — must choose from the four different modes of emplotment: romance, tragedy, comedy, satire (anti-romance). As White puts it, ‘a given historian is forced to emplot the whole set of stories making up his narrative in one comprehensive or archetypal story form‘. (p. 137, John As Storyteller)

I have highlighted the words “must choose”. There is nothing inevitable about the way a story-teller (or historian) decides to “emplot” his narrative. Had the author of the Gospel of John been looking back on a life of someone he knew first hand he would have been free to construct that life as any one of the four different modes of emplotment: romance, tragedy, comedy, satire. The simple fact that subsequent lives of Jesus have chosen to depict it ways other than tragedy tells us clearly enough that Stibbe (like Bilezikian) is mistaken when they claim that the life of Jesus was written like a Greek tragedy on a stage because that’s how it was in real life. Historians and storytellers must always make decisions about what details to include, what interpretation to give them, and how to present or narrate them.

(Comedy in this context, by the way, for those not familiar with literary studies, basically means a story with a happy or at least non-tragic ending. It does not have to be a Spike Milligan script throughout. Some scholars have suggested that the Gospels could be considered closer to comedies than Greek tragedies.)

So how do we explain the similarities?

Most of Stibbe’s “very general” similarities above are by no means essential ingredients for tragedy. Indeed they are very specific to both the Bacchae and Gospel of John.

A deity returns to his own people, his own land, disguised as a human, is not recognized, is even rejected, but there is one person there who still believes and testifies truly.

At the same time it is clear that the Greek prologue has little in common intertextually with the prologue of the Fourth Gospel.

For Stibbe, the answer is that the life and reality about Jesus happen to be coincidental with key facets of the play about Dionysus. The evangelist singled out historical details that he believed related the essence of the Jesus (tragedy) story.

The reality is, however, that we know nothing about the historical life of Jesus apart from the gospels (the epistles tell us little more than the theological-faith event that he died and rose again). Stibbe and Bilezekian are reasoning in a circle when they argue that the life of Jesus was in reality structured or plotted just as we read it in the Gospels.

That leaves us with the likelihood of some relationship between the play and the gospel. We will later look beyond the play and at the wider constellation of “mythemes” associated with Dionysus.

Mythemes

According to anthropologist Levi-Strauss myths are composed of small units or mythemes that can be compared with phonemes in language. Phonemes have no meaning on their own but only in relation to other phonemes. Likewise mythemes (small narrative units within any one myth) have “no universal or archetypal meaning” but only take their meaning in the context of each larger narrative. (I did not like that idea all those years ago — I wanted them to contain hidden archetypal or Jungian messages to unlock mysteries.)

According to Levi-Strauss, a myth tries to answer questions from day-to-day life yet never reaches an answer. Therefore, any new narrator of a myth will change small or large details, so much that all logical possibilities will be explored until the myth reaches exhaustion. (p. 17, Argonauts of the Desert)

As I more or less wrote in another post some time ago, if we embrace Lévi-Strauss’s view of myths, then the myths of early Christianity can only be understood and explained as mutations of similar myths in other cultures, and in the case of the Gospels both Jewish and Greek cultures are relevant. So the Christian myths are not unique. Their constitutional ties with other myths are integral to understanding them. The Christian myths must be understood as myths no different in essence from any other myths if one can identify clear similarities (as in identical “mythemes” — units of mythical stories regardless of their place in each myth) between them.

We have all wondered about the strange mix of “same but different” elements across different myths. Serpents appear in many origin myths, but why is the serpent a beneficent creature bestowing wisdom in some myths yet evil (because of the wisdom bestowed) in others? Why do we find a plucked fruit in one myth leading to doom for all mankind, yet in another myth we find a plucked plant in very different scenes offering life but being responsible for death for a hero in another? Lévi-Strauss’s approach begins to make sense of this sort of thing.

I also suspect that the same approach makes sense of the “same but different” myths we find in the Gospels vis-a-vis certain pagan and Jewish myths.

This means that in the case of the Bacchae and Fourth Gospel we will need to learn if the similarities extend beyond the play and the gospel.

But first, let’s see what else Stibbe finds in common between these two. (Though some of the comparative passages from the Bacchae are my own.)

(One detail not addressed by Stibbe, and one that may or may not be worth keeping on the shelf in case we find a reason to call upon it for future reference, is that soon after the play’s Prologue Cadmus, the one voice whom Dionysus praised for his faithfulness in his opening address, is led by the aged, blind and wise prophet, Teiresias, to the worship of Dionysus.)

More similarities in John 18 – 19

The binding of the human-forms of the deities

In John 18:12-27 Jesus is arrested, bound and taken away as a prisoner. Jesus was always depicted as in total control of events, allowing himself to be bound and taken away. He did not resist. Compare Dionysus, likewise in total control, submissive, being led away. In the following passage the royal servant is telling his king how easy it was to bind the one who was (unknown to them) really Dionysus:

We found or quarry tame; he did not fly from us, but yielded himself without a struggle; his cheek ne’er blanched, nor did his ruddy colour change, but with a smile he bade me bind and lead him away, and he waited, making my task an easy one.

It is significant that the only Gospel that specifically says Jesus was bound is John’s. And he twice makes the point that Jesus was bound — both to be taken to Annas and then to Caiaphas.

Stibbe actually is trying to follow the play too closely and uses as the parallel in the Bacchae a scene where Dionysus is not really bound at all. Stibbe chooses the scene where Dionysus tricks his jailer into binding a bull thinking that he really binding Dionysus. He wants this to be the binding scene because it is adjacent to the final “passion” or suffering scene — as is the scene of Jesus being bound adjacent to his suffering.

But if we are assessing both the gospel and the play for mythemes, it is best to identify what truly are matching details regardless of where they appear in the different myths.

What is just as significant is that the reason both Dionysus meekly accept being bound and led to the authority (king or priest) is that they are, in reality, behind their human “masks”, the very powers of deities, unrecognized, opposed, and on trial.

The stories part – the mythemes remain

The second time that Dionysus is led off to be bound (recall that John speaks of Jesus twice being bound as he is taken to two different places), it is on the orders of King Pentheus to be kept and bound in prison.

Jesus is sent to Caiaphas, a further trial, bound, and then to Pilate and crucifixion.

The Greek god will not allow himself to go the way of Jesus, however. Once in the prison he uses his miraculous powers to confuse the poor guard into thinking he is tying up Dionysus when in fact he is tying up a bull.

In both gospel and play, the two sides of the drama are either in their right minds and know the truth or are blind, mad and deluded.

Having fooled the guard into thinking he has bound Dionysus, the god then begins to use his divine powers to reveal himself and punish the arrogant and spiritually blind king. He causes a great earthquake that results in the prison gates being flung open and then the complete collapse and burning of the king’s palace.

We know Jesus has the power to wreak the same havoc but that he chooses not to use it.

The two trials

We know the famous trial of Jesus before Pilate. Jesus answers in mysteries that only confuse his interrogator. The dialogue is a series of brief exchanges in which we know Jesus is speaking from a higher wisdom and understanding hidden from Pilate.

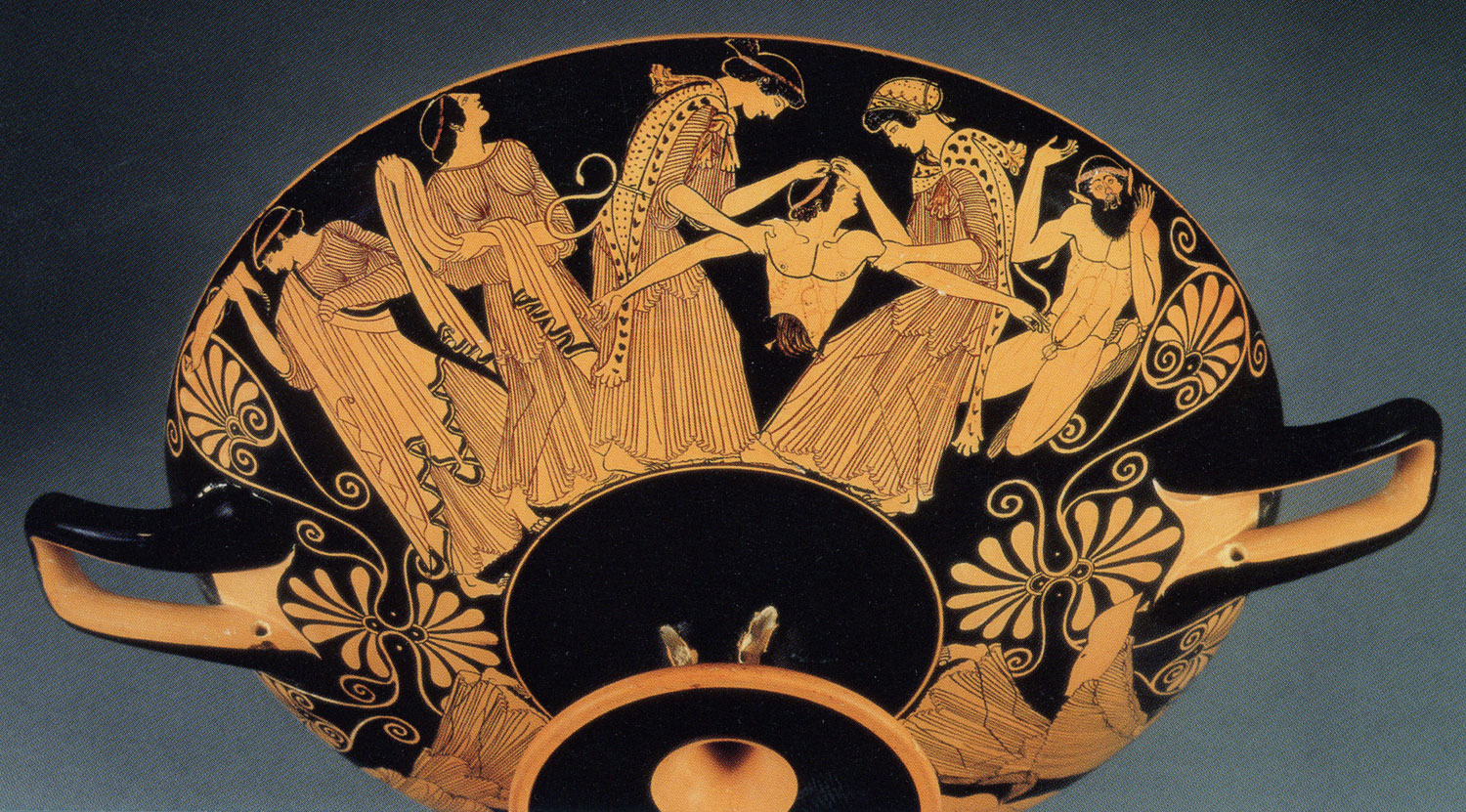

Here is the trial scene. Dionysus is before the king, Pentheus:

Pentheus

. . . . First then tell me who your family is.

Dionysus

I can tell you this easily, without boasting. I suppose you are familiar with flowery Tmolus.

Pentheus

I know of it; it surrounds the city of Sardis.

Dionysus

I am from there, and Lydia is my fatherland.

Pentheus

Why do you bring these rites to Hellas?

Dionysus

Dionysus, the child of Zeus, sent me.

Pentheus

Is there a Zeus who breeds new gods there?

Dionysus

No, but the one who married Semele here.

Pentheus

Did he compel you at night, or in your sight?

Dionysus

Seeing me just as I saw him, he gave me sacred rites.

Pentheus

What appearance do your rites have?

Dionysus

They can not be told to mortals uninitiated in Bacchic revelry.

Pentheus

And do they have any profit to those who sacrifice?

Dionysus

It is not lawful for you to hear, but they are worth knowing.

Pentheus

You have counterfeited this well, so that I desire to hear.

Dionysus

The rites are hostile to whoever practices impiety.

Pentheus

Are you saying that you saw clearly what the god was like?

Dionysus

He was as he chose; I did not order this.

Pentheus

Again you diverted my question well, speaking mere nonsense.

Dionysus

One will seem to be foolish if he speaks wisely to an ignorant man.

Pentheus

Did you come here first, bringing the god?

Dionysus

All the barbarians celebrate these rites.

Pentheus

Yes, for they are far more foolish than Hellenes.

Dionysus

In this at any rate they are wiser; but their laws are different.

Pentheus

Do you perform the rites by night or by day?

Dionysus

Mostly by night; darkness conveys awe.

Pentheus

This is treacherous towards women, and unsound.

Dionysus

Even during the day someone may devise what is shameful.

Pentheus

You must pay the penalty for your evil contrivances.

Dionysus

And you for your ignorance and impiety toward the god.

Pentheus

How bold the Bacchant is, and not unpracticed in speaking!

A point not noticed by Stibbe is that the king is, not unlike Pilate, somewhat impressed by his prisoner despite his need to punish him. As in the Jesus-Pilate trial, the audience is aware of the double meanings in the words of the god and that confuse or baffle the judge. Some of the ironic words of the prisoner are also, in reality, hidden judgments or sentences pronounced upon the king (or governor).

The question of origins remains a mystery, too, for those who oppose both Dionysus and Jesus.

The humiliation

We know of the humiliation of Jesus, how he was mocked, scourged, adorned with a crown of thorns and a cloak of royal purple, and hailed as king in a mock ceremony.

The humiliation in the Bacchae, however, is not experienced by Dionysus but by the king who attempted to punish the god, Pentheus.

Stibbe mistakenly thinks the evangelist is “subverting” the idea of a Greek tragedy with this switch. I think a simpler explanation is that we are witnessing a retelling of the myth, the same mythemes, but being tested in a new plot line for the values of the new religion.

Pentheus’ humiliation is being made to dress in the appearance of Dionysus himself — Dionysus, for all his power, takes on a most effeminate look — and of his women followers.

Dionysus

I will go inside and dress you.

Pentheus

In what clothing? Female? But shame holds me back.

. . . . .

Dionysus

I will spread out hair at length on your head.

Pentheus

What is the second part of my outfit?

Dionysus

A robe down to your feet. And you will wear a headband.

Pentheus

And what else will you add to this for me?

Dionysus

A thyrsos in your hand, and a dappled fawn-skin.

Fastened to a tree for divine vengeance

We know the story of Jesus being crucified, with women followers looking on.

The one who dies in the play is Pentheus, the king who condemned Dionysus and his worship. (I have added a few details of comparison in what follows not brought out by Stibbe.)

Dionysus led him out to where he was to die — in humiliation, dressed like a woman and a disciple of Dionysus himself — to the place where his worshipers were gathered for their sacred rites.

Dionysus persuaded Pentheus to be fastened to a tree-top for a better view of the secret rites. Once he had miraculously placed Pentheus there he called out in his thunderously divine voice from heaven to tell his worshipers to look and see the one who mocked and persecuted them and to punish him.

Not unlike the thunderous voice in the Gospel of John that hearers did not at first understand (John 12:28-29), the women devotees were at first confused, not knowing what they had heard. The voice spoke a second time and this time the women acted. They turned and saw Pentheus strapped high in the tree, ran towards him, attempted to stone him but he was beyond reach.

Infused with divine frenzy they managed to tear the tree down to reach their victim.

Pentheus cried out in sorrow.

His mother was the first of the spirit-possessed women to reach him so he ripped off his head-band and called out to her to recognize him, that he was her son. Quite a different mother-son dialogue from the one we read in the Gospel of John.

His mother was the first of the spirit-possessed women to reach him so he ripped off his head-band and called out to her to recognize him, that he was her son. Quite a different mother-son dialogue from the one we read in the Gospel of John.

The women, filled with divine power and madness, tear Pentheus limb from limb.

The scene can be read online beginning from this section.

Specific similarities noted by Stibbe:

- A king is led out of the city to a hill or mountain;

- A king is lifted up;

- Women play a vital role.

I have noted others above.

Of course Stibbe is quick to point to the obvious differences. Outstanding among these is the contrast of Pentheus crying out “Mother, it is I, your son!” with Jesus’ affirming to the Beloved Disciple, “Look, your mother.”

A subversion of Greek tragedy or recycled mythemes?

The recognition scene

Both the play and gospel climax with recognition scenes after the tragic death of a central character. We know of the slowly dawning recognition by Mary (and the disciples) of the Jesus who was crucified.

The climactic conclusion of the play is when the mother of Pentheus slowly comes to recognize that the head she is holding is really her son’s. Her punishment — for initially disbelieving in Dionysus and mocking him, accusing his mother of bearing him in sin to a human father — is now complete, too.

Continuing . . . . .

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Back when I was a Christian believer I reasoned that God had ordained that many of the world’s myths would be allowed to take shape as sort of a shadows-in-the-cave-like stories of the real story of Christ. I thought of them as testimony to an actual pre-existing human “joy of man’s desiring” played out in myths.

The trend over the last decades has been to find points of differences between the Christian and other myths and kind of use them in some sort of crude ledger: similarities are only allowed to count if they overwhelmingly outnumber the differences. Or (as Stibbe and Bilezekian do) attribute the similarities to coincidence. That’s not how we approach non-Christian myths.

A view shared by others like the Jungian Victor White OP in “God and the Unconscious” and if my memory is correct also Cardinal Newman.

The FG is a theological drama in which Jesus is sequential revealed as the Emanation of Deity. Events or themes found in the synoptics are taken and given fresh symbolism; one miracle at the wedding; one raised from the dead (Lazarus); one woman at the resurrection (Magdalene). I see it as an ancient literary tour de force. The discourses might seem appropriate to the Greek stage. The supposed addition in which the fishermen see a brazier on the shore would go neatly in a modern film.

Do you know of any works that discuss the Gospel of John as a drama? What do you see as the reasons for this interpretation?

I value your analysis of M W G Stibbe on e.g. Euripides.

See: J A Brant, “Dialogue & Drama: Elements of Greek Tragedy in the Fourth Gospel” (2004); G L Parsenios, “Rhetoric & Drama in the Johannine Lawsuit Motif” (2010); R A Culpepper, “Anatomy of the Fourth Gospel” (1959); D B Pratt, “The Gospel of John from the Standpoint of Greek Tragedy” (1907). Others include: F R M Hitchcock, C R Bowen, C M Connick, J L Martyn, E L Pierce & N Flanagan.

Unlike the Synoptist eschatological parable-telling exorcist, the Johannine egoist resembles “a celestial being in human disguise, who came from above and was to reascend” (G Vermes). In specific “acts” (signs), in “soliloquy” (doctrine) and in plot, he transcends the other gospel narratives, the Word made flesh finally receiving adoration by Thomas.

My thoughts were influenced long ago mainly by drama-critic J M Robertson’s theory of a mystery-play transcript (“Short History of Christianity” [rev. 1931] pp.9-11), and by translator E V Rieu’s observation: “John is above all things a dramatist. It is not unlikely that he had read Euripides and Plato. His scenes and dialogues often remind me of the technique of earlier Greek writers….at the empty tomb, has any dramatist ever put into the mouth of any character a one-word utterance so charged with emotion as Jesus’s ‘Mary’?” (“The Four Gospels” [1952] pp.xxviii-xxx).

Apparently some Roman executions were staged as mythological enactments. As for a “Gospel According to Seneca” (q.v. on-line) this seems about as plausible as (say) S F Sage’s “Ibsen and Hitler” (2007) from a “converse” perspective.

Can we all agree that the FG provides a “dramatic interpretation” (M M Thompson)?

“his devotees are not, as Pentheus impiously suspects, hiding in the woods to engage in hedonistic sexual practices.”

Well that’s a disappointment.

“But certainly the god of the play is a god of implacable vengeance against unbelievers.’

In this, John divagates from the Synoptic Gospels and the Old Testament. The unrelenting vindictiveness Paine referred to hardly shows in the fourth Gospel.

This means that in the case of the Bacchae and Fourth Gospel we will need to learn if the similarities are extend beyond the play and the gospel.

Dennis MacDonald is publishing a book on this very topic. He presented a paper on it recently at SBL International in St. Andrew’s.

You have a link?

Unfortunately not. The book will be about John, Dionysus and Plato.

Bibliograpic cites and useful video link:

The Gospels and Homer: Imitations of Greek Epic in Mark and Luke-Acts. Vol. 1 of The New Testament and Classical Greek Literature (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

The Gospels and Vergil: Imitations of Euripides, Plato, and Homer in the Aeneid; Luke-Acts, and John. Vol. 2 of The New Testament and Classical Greek Literature (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

Forthcoming: John and Euripides: Imitations of the Bacchae in the Fourth Gospel. Vol. 2 of The New Testament and Classical Greek Literature (Rowman & Littlefield, forthcoming).

Dennis MacDonald : “John’s Dionysian Gospel: Imitations of Euripides’ Bacchae

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gxHvhx6g2wI

No mention of King Pontius as the resurrected Pentheus? No mention of the fifth? Pontius the fifth procurator. Behind The Name: Roman family name. The family had Samnite roots so the name probably originated from the Oscan language, likely meaning “fifth” (a cognate of Latin Quintus).

No Python, Typhon, Neptune?

Ever notice how the scholars fail to recognize the god?