Let’s imagine that oral traditions among today’s bedouin Arabs may be able to guide us in understanding how oral traditions worked in the days when the Bible stories were being originally told. — But don’t misunderstand. The Bible stories, even if they were originally sourced from pre-literate oral tales, have been artfully constructed to convey theological messages. But even the pre-literate oral traditions among Arab tribes have been re-written (sometimes for modern film) in ways that bear little resemblance to the themes of the original. What I am trying to imagine here is the evidence for the original biblical tales and how they compare with what we know of

Let’s focus on one Bible story for exercise, the story of David, and compare its elements with what we know about story-telling among peoples with long traditions in the Middle East. Incidentally, let us ask how one can know if an oral tradition has any historical basis at all.

That’s what Eveline J. van der Steen did when she wrote “David as a Tribal Hero: Reshaping Oral Traditions”, a conference paper eventually published in Anthropology and the Bible: Critical Perspectives (edited by Emanuel Pfoh). (I’ve added my own little asides reflecting on potential relevance for what we read in the Gospels.)

That’s what Eveline J. van der Steen did when she wrote “David as a Tribal Hero: Reshaping Oral Traditions”, a conference paper eventually published in Anthropology and the Bible: Critical Perspectives (edited by Emanuel Pfoh). (I’ve added my own little asides reflecting on potential relevance for what we read in the Gospels.)

Arabs had and have a plethora of vernacular traditions: various forms of poetry, genealogies, epic legends and tribal histories. Oral traditions are a rich source of information, provided they are eventually written down and preserved. (p. 127)

And written down and preserved many have been since the 20th century when literacy pervaded a critical mass of the Arab world. Until then they relied entirely upon storytelling, citing and singing for their preservation.

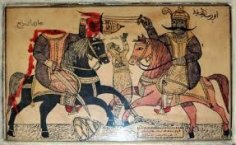

One form of oral tradition that can be traced back to pre-Islamic times is the akhbar, “short stories, recounting the adventures and battles of the various bedouin tribes.” Again going back to pre-Islamic times story telling competitions were held among the various tribes.

.

Features of the stories

- Usually focused on one tribal hero

- Eventually grew into tribal heroic cycles

- Recited by professional storytellers

- Recited in desert tents and coffeehouses of towns and villages

- Told or chanted (often a mixture of both) in prose or rhyming prose, interspersed with poetry.

Every Arab knew parts of these stories: they were, and still are, part of the national culture. (p. 128)

Nineteenth century Orientalist Edward Lane described how storytellers would come into coffee houses in Cairo, recite and/or chant their stories about tribal heroes, then — at an appropriate cliff-hanger moment — stop for the evening to ensure an audience for the next day.

That way a story session could last well over a year.

The storyteller would develop the story as he went along, borrowing from his repertoire of other stories and formulas, adapting the story to the audience and situation. So the audience itself played a critical part in the development of the story:

they expressed their approval or disapproval, and discussed the story with the narrator. In town the stories reflected life in the town, in bedouin camps the context would be the camp. Only the main storylines, and the heroes remained the same. (p. 128)

That’s interesting. Ought we therefore conclude, if we are to apply this to the common belief among New Testament scholars that Gospel stories generally began as oral traditions, that these oral traditions about Jesus point to the settings where the stories were told rather than to a historical setting? Would it not follow that the Galilee and lakeside settings might be nothing more than pointers to the location of the taverns where the stories were told prior to being recorded?

We can see here, furthermore, the reason many oral traditions lack a final, definitive form, or even coherence within the story.

Stories contributed to ethnic and social identity. They could also be told as expressions of political discontent among the otherwise powerless. So even when the stories were eventually written down by a local or national ruler, story variants continued to flourish as storytellers continued to borrow and adapt in response to audience feedback. Stories of ancient heroes were also often transferred to modern heroes.

Again, one must ask if there is potential relevance here for New Testament scholarship entrenched in the idea of Jesus stories being passed on through oral traditions. Are such stories so flexible that existing tales of other heroes — perhaps even biblical ones — were adapted and applied to a Jesus hero? Some scholars say such things could not happen because there would be witnesses to call the storyteller to account. But it appears from these bedouin cases that that’s not how story-telling and oral traditions work.

As a result of this free traffic in tales and legends the history and historicity of many classic heroes has become blurred. Nevertheless, some of the most famous story cycles had a traceable historical core: the sirat Baybars focused on the famous Mamluk sultan, the Sirat Ben Hilal on the exodus of the Beni Hilal tribe into Egypt and eventually into north Africa, both episodes in history that are well documented.

Peter Heath (1966:22-23) likewise believes that Antara ibn Shaddad was a historic figure. He was the son of a member of the north Arabian tribe of Beni Abs and a black slave woman. He gained his freedom through courage in battle, and died of a ripe old age early in the 7th century, possibly in a sand storm.

The historical Antara was overshadowed quickly by the legendary Antar, subject of the Sirat Antar, according to Heath possibly already during his lifetime. (pp. 129-130)

Van der Steen speaks of some stories relating to historical cores that are “well documented” but does not explain the basis for Heath’s conclusion that Antara was historical.

Here are some central themes recurring in these hero epics. Some of these are, as we would expect, “universal in oral traditions worldwide.”

1st: The Rise of the Hero

The birth and early youth of a prospective hero are surrounded with magic, misunderstanding, and omens. A hero’s start in life is usually troubled: a barrier to overcome on his way to heroism. He is either of low descent, a slave like Antar, or, as in the case of Abu Zayd, hero of the Beni Hilal, his real parentage is hidden from him. When Abu Zayd’s mother was pregnant, she had a vision. As a result the hero was born black, with dire consequences for his mother and himself. They were expelled from the tribe, and he grew up in an enemy tribe, unaware of his high parentage. (p. 130)

At the same time, the hero during his youth “usually reveals qualities that foretell his special destination.” — There is some feature about him that stands out — his huge size, his strength, his fierce character, his intelligence. Thus Abu Zayd mastered the arts of astrology, magic, alchemy and other branches of knowledge before he was twelve years old. (Compare what may be the last completed gospel — Luke — depicting the twelve year old Jesus astonishing the doctors in the Temple with his wisdom.)

The hero must perform special deeds and show special skills to earn his due recognition among not only his enemies but also, and especially, among his own tribe and family. Often the hero will leave his family, perform heroic deeds, then return to claim acceptance among his people.

Antar does this several times. During his time away he gathers followers who are often the outcasts of society, leads them on raiding expeditions, and relies upon them as his special guard and army when he comes to power. Antar becomes an especially skilled warrior and acquires various trappings that appear to have “almost magical value”: his horse al-Abjar, his sword ez-Zami (the Thirsty). His half-brother Shaibub becomes his very close friend.

2nd: The Love Stories

The hero must win his beloved by performing heroic deeds fighting rivals or an unwilling father-in-law. One common theme is the impossible dowry — a ploy that is clearly hoped to lead the hero to his death. Antar must steal one thousand camels from the king of all Arabs as a dowry for Abla.

There would often be accidental encounters in unusual places and circumstances, “giving a decidedly erotic flavour to some of the episodes, something the audience loved.” Sometimes a description of the beauty of a woman was enough to infatuate the hero.

3rd: His Role of Service

Once the hero has been recognized, his main purpose in life is to protect and serve the society that has proclaimed him their champion.

The hero still does the same sorts of things. He still

fights, rescues, raids, attacks, defends and celebrates victories. But his main goal has changed: the hero serves his people.

4th: Poetic Skill

Heroes were seen as great poets.

Abu Zayd often disguised himself as a professional poet, and astonished everyone with his skill.

5th: The Hero’s Code

When a conflict arose between the laws of his society and the code of honour a hero was entitled to follow his own code. So he will protect strangers, even against the laws of his tribe, if necessary; or he will forgo the duty of revenge in preference for mercy if he wishes.Otherwise, the hero would conform to all that was expected of him: loyalty to his tribe, defending and revenging others, behaving honorably, etc.

6th: The Death of the Hero

Seldom is the hero allowed to die a natural death in old age. He is sometimes killed in battle, but more often dies in “an accident, an act of fate, magic or cunning by an enemy.

The death scene and mourning are expanded upon in the narrative, but most important is that the death of the hero gives rise to the theme of revenge and the opportunity for more narrative. (p. 132)

.

Comparing the narrative cycle of David

The tales of David in 1 and 2 Samuel, like many of the heroic epics of the Arab tribes, are built upon universal themes common to most oral traditions in various cultures.

But van der Steen looks beyond these universals and “strikingly similar” patterns between the story cycle of David and that of Antar as told in the Sirat of Antar.

Which poses the question whether the oral traditions that lie at the root of the stories in the books of Samuel are rooted in a heroic epic comparable to the Siras. (p. 132)

Again, as I pointed out at the beginning, we are not suggesting that the story of David as we read it in the Bible was a transcription of an oral legend. No, the biblical tale has clearly been edited to serve as theological or nationalistic propaganda. But then, van der Steen points out, many bedouin epics have also been modified to serve nationalistic agendas: see http://www.peplums.info/pep04.htm

Again, as I pointed out at the beginning, we are not suggesting that the story of David as we read it in the Bible was a transcription of an oral legend. No, the biblical tale has clearly been edited to serve as theological or nationalistic propaganda. But then, van der Steen points out, many bedouin epics have also been modified to serve nationalistic agendas: see http://www.peplums.info/pep04.htm

Sirat Antar has been turned into numerous movies, some of which have little or no connection with the original narrative anymore. (p. 132)

Notice the first three themes cited above — the rise of the hero, the love stories, and the heroic service — and compare with the David story. Eveline J. Van der Steen makes special mention at this point of these first three, but the subsequent text addresses more.

1st: The Rise of David

Quickly refresh our memory by scanning the features of the Rise of the Hero above — disadvantage, startling deeds setting the hero apart, struggle for recognition among his own. . . .

David is the youngest of his family and that alone sets him at a disadvantage. When Samuel visits David’s father makes it clear that he thinks David can be of no interest to the prophet.

Despite this negative assessment by his own family, Samuel predicts future greatness for David.

As a youth David distinguished himself by killing a lion and a bear with his bare hands and slaying the giant Goliath.

David acquires the sword of Goliath, which, in the original version, may well have had magic qualities.

The struggle for acceptance among his own group, or the group for which he was destined, begins its dramatic tension when David establishes a “life-long friendship with his spiritual half-brother, Jonathan.”

This relationship will remain ambivalent well after the deaths of Saul and Jonathan.

Both David and Antar — when at loose ends in their own lives — attract large bands of devoted followers from the ranks of the outcasts of society. This band become the personal bodyguard of the hero and core of the eventual standing army. (Antar’s followers were mainly deserters from the Egyptian army, as well as slaves and other castaways.) When the hero achieves power his band of followers shift from being raiders and looters to police-forces ensuring stability and justice.

Likewise David, as we know, gathered the disenfranchised and lived as a raider in the wilderness after he was cut off from the House of Saul.

After David becomes king the story moves into a scene common to tribal societies: tensions between the tribes of Benjamin (Saul’s tribe) and Judah (David’s).

2nd: The Love Stories

David’s first love story required of him to collect the impossible dowry clearly intended to see him killed: one hundred foreskins of the Philistines for King Saul’s daughter, Michal.

Then there was Abigail, the “brave and wise woman who came to apologize for the fact that her foolish husband Nabal had refused to give in to one of David’s protection rackets.”

The laws of heroic romance dictate that David and Abigail should fall in love when they meet, and conveniently, Nabal died a few days later so they could marry. (p. 134)

As for Bathsheba?

Bathsheba was the manipulative beauty, who arranged a surprise erotic encounter, bathing on the roof.

3rd: David’s Role of Service

After he became king David served his people by defeating their enemies and expanding their territory. Time and again challengers rise up to overthrow him but he always prevails.

4th: Poetic Skill

David’s reputation as a poet was such that practically all the poetry in the bible has been ascribed either to him, or to his no less heroic son Solomon. (p. 134)

5th: David’s Personal Code

David’s personal code of heroic honour transcends and violates the tribal code of his time. Thus he refused to kill his enemy Saul. Further, he protected and even avenged Saul’s surviving family.

.

Origin and meaning

van der Steen concludes that the political organization depicted in the story of David is “tribal and largely predatory.”

Raiding and robbing, with a band of predatory outlaws, and protection practices were seen as perfectly legitimate and respectable in bedouin society until well into the 20th century. They were a means to establish power relations. (p. 134)

The custom of single combat to replace or precede a major battle is another common feature of tribal competition. And as mentioned above, the rivalry between Benjamin and Judah after David’s rise reflects typical pre-World War 1 politics of the region.

We began with an explanation of how the audience influenced the way a story was told, and here is where van der Steen sees the influence of audiences living within a stable and urban-based kingdom. The bedouin setting, she suggests, has been transformed to conform to the world of ruling king and “an established kingdom with well-defined power and territory, but in which the tribes that constitute it still played a major role.”

It was through “retelling and reinventing” in the new setting that the biblical story of David took shape and served as a symbol of Israelite identity. The role of the Deity was introduced and became a major structural unifier, and enjoined a belief system for subsequent audiences.

All this sounds most plausible enough, but don’t jump too quickly. Consider, firstly, the arguments of van Seters that see the same motifs in David’s story as evidence of an imperial Persian context: see my three earlier posts on

All this sounds most plausible enough, but don’t jump too quickly. Consider, firstly, the arguments of van Seters that see the same motifs in David’s story as evidence of an imperial Persian context: see my three earlier posts on

for some details.

But from another perspective to that of Van Seters I hope also soon to post on a work I found particularly intriguing, The Faces of David by K. L. Noll.

Consider, meanwhile, the newer arguments that the establishment of the Persian colony of Jehud, as was the case of other deportations in the time of the Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians (that is, resettlement for economic, military or other reasons, through mass deportation, and with willing or unwilling settlers being informed they were returning to the land of their ancestors and their god) — consider the possibility that this Persian colony of Jehud was actually the very first appearance of “Jews” in the land. Would we not expect to find similar motifs?

- a need to identify with an image of being strangers to one’s home, but facing rejection despite imperial and possibly religious (divine) decree that they settle there

- the overcoming of many obstacles in the quest to find “one’s place” in one’s new home

- the need to rationalize different codes of conduct

I’m not saying by any means that these motifs would have been invented to serve such a purpose. Their roots in common Middle Eastern folk tales are too well established for that. But such motifs could certainly find added relevance and take on new meanings in a society destined for dominance that found itself, by divine decree, in a land of strangers. Compare the myths of early Christians in the Gospels. Do believers today who cling to them find themselves in a somewhat comparable environment and is that why they hold such an attraction?

Bible stories are popular. They are adaptable. They can function at different levels and for different needs. Just some concluding thoughts.

.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

To appease my erstwhile atrotheology friends I should add that yes, I am aware of the claims that elements of David’s story grew from solar myths. Goldziher writes:

I never thought of the midday sun as red. I had understood the Egyptians had a special name for the sun on the horizon as it turned red.

Again on page 430:

So there you have it. This information is not suppressed or banned on this blog after all. I just didn’t see its relevance for the topic that grabbed my interest for this post.

Your topics lately should greatly strengthen the case for Mythicism … by at last accumulating a solid academic bibliography for Mythicists to cite, against historicists.

Historical Jesus scholars tend to read only their own works – and to ignore countless relevant works outside of their own too-narrow, self-satisfied field. Though they sometimes give lip service to other fields outside their own, to “interdisciplinary” studies, they clearly have neglected – and are simply ignorant of – many relevant studies outside their own narrow field of attention. In particular, this brief article from a scholarly Anthropologist, is a good first academic article to cite in support of Mythicism. And to point out to Historical Jesus religious studies scholars, the kind of scholarly information they are ignoring.

It is often said in Historical Jesus studies, that tales of “Jesus” were transmitted in part “orally,” for many years, before being firmly codified in the written works of Paul and/or the gospels. But if so, then it is time for Mythicists to note that clearly the Science of Anthropology shows that there is more than enough flexibility and looseness, in oral transmission of legends and stories, for massive amounts of invention, elaboration, confusion, and so forth.

If there are any historical elements at the source of Jesus tales at all, this and many other Anthropological and Folkloristics studies show that the oral traditions that governed Jesus tales for some time, would almost have certainly elaborated on that history. Adding and subtracting countless elements. To the point that the final result could easily have been largely – and even possibly entirely – historical fiction, or mere “legend.” Rather than useable history.

The assumption made by these scholars is that Christians only told stories to other Christians. If that were the case, then Christianity would have never spread beyond the initial followers. By definition, shouldn’t storytellers be telling stories to people who don’t already know the story? Wouldn’t that be the vast majority of who the storyteller’s audience be?

Good point. Especially the Gospel of Mark looks as if it was specifically written for people who had never heard about this story, let alone Jesus. Which was probably an additional reason why there was a need to rewrite it at some point, besides the wish to include some other stories of the hero.

Some scholars say such things could not happen because there would be witnesses to call the storyteller to account.

Why can’t those scholars look around today? A good proportion of what we think we know of the America’s founding fathers and American history is myth. (Betsy Ross and the flag, George Washington and the cherry tree, Paul Revere yelling “the british are coming.”) or even modern day (Obama is from Keyna..). Truth rarely trumps a good story. Add in religion, and truth never wins.

Also, it is possible that when the first story tellers where telling the stories, everyone knew that it was entertainment. People didn’t object because there was no need to. Only later, when those with first hand knowledge are no longer there, does the story go from entertainment to fact.

Higgs Bosons