Now for something light. It comes from a book by two professors at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Avigdor Shinan and Yair Zakovitch, titled From Gods to God: How the Hebrew Bible Debunked, Suppressed, or Changed Ancient Myths & Legends, published 2004 by the Jewish Publication Society. Chapter 14 explores the curious episode that led a hungover Noah to curse Canaan, the fourth son of Ham.

Now for something light. It comes from a book by two professors at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Avigdor Shinan and Yair Zakovitch, titled From Gods to God: How the Hebrew Bible Debunked, Suppressed, or Changed Ancient Myths & Legends, published 2004 by the Jewish Publication Society. Chapter 14 explores the curious episode that led a hungover Noah to curse Canaan, the fourth son of Ham.

We know the story in all its vagueness. After the flood Noah became the first in the new world order to plant a vineyard, to make wine, and to get blind drunk. We read that while drunk the good saint

was uncovered in his tent. And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without.

And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness. (Gen. 9:22-23)

So we are being told that there is something so terrible about seeing one’s father naked that it needs to be recorded in the Bible for all posterity to read.

But look at the punishment that follows:

And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him.

And he said, Cursed be Ham Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. . . . (9:24-25)

I added and crossed out Ham there to draw attention to the bizarre detail that it was not Ham, Noah’s younger son who saw him naked, who is cursed, but Ham’s son. And not just any son, but his fourth son:

And the sons of Ham: Cush, and Mizraim, and Phut, and Canaan. (Gen. 10:6)

The mystery thickens.

Now many of us savvy sophisticates know that when the Bible speaks of “seeing the nakedness” of someone it is euphemism for having sex. Leviticus 20:17 leaves no doubt:

If a man takes his sister, his father’s daughter or his mother’s daughter, and sees her nakedness and she sees his nakedness, it is a wicked thing. And they shall be cut off in the sight of their people. He has uncovered his sister’s nakedness. He shall bear his guilt.

So this makes a bit more sense than Ham merely peeping at his naked father. Noah did, after all, know what Ham had “done unto him”. That’s a bit stronger than having a peek.

But that still doesn’t explain everything. Why did Noah curse Canaan, Ham’s fourth son?

As we read the following books in the Bible we see that the Canaanites were notorious for their sexual license and so were the Egyptians who were also descended from Ham. So perhaps here is an indication that Ham’s sin involved a sex act? Not entirely a satisfactory explanation, is it.

Stepping Back for a Closer Look

Here’s where Avigdor Shinan and Yair Zakovitch take a literary step back and view this episode in its broader structural context.

Before the flood recall that one of the sins that upset God so much was the fallen angels lusting after and procreating with human females. Then not long after the flood Ham does something relating to illicit sex to his father. Sin is ever the human condition. God just has to learn to be patient if he wants humans to populate the earth. But consider another subsequent tale of annihilation — Sodom and Gomorrah. In that case, it is the humans who lust after and want to have sex with the angels who are visiting Lot. Not that they know they are angels, of course, but we do see a curious chiastic or sandwich structure here either side of the Noah-Ham filling.

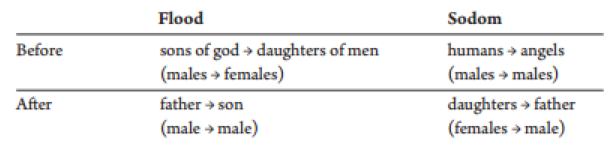

It gets more interesting as we zoom in for a closer look. Here’s a little diagram produced by the authors to help explain the way it works:

Before the flood the fallen angels “went unto” the daughters of men. Before the destruction of Sodom the wicked men wanted “to have” the male angels sheltering with Lot.

Before the flood the fallen angels “went unto” the daughters of men. Before the destruction of Sodom the wicked men wanted “to have” the male angels sheltering with Lot.

After the flood a son “sees the nakedness” of his father (I think the diagram is a bit askew there); after the destruction of Sodom the daughters have sex with their father Lot.

Before the flood there is illicit male-female sex and after Sodom there is illicit male-female sex.

Before the flood there is illicit male-female sex and after Sodom there is illicit male-female sex.

After the flood there appears to be illicit male-male sex and before Sodom’s demise there is an attempt to have illicit male-male sex.

Moreover, getting blind drunk is an essential part of each story. Both Noah and Lot become so drunk that they don’t know what is happening to them.

Noah knows what has happened when he recovers, however. So he curses Ham’s fourth son. We’re coming to that.

Lot does not know what has happened and does not curse anyone. The children are later cursed in the biblical narrative, though (Deut 23:4). Later rabbinic readings, however, did find a way to interpret the Genesis account to mean that though Lot did not know when one of his daughters came to lie with him he did register her getting up and leaving. This appears to have been an attempt to connect the stories of Noah and Lot more closely. Was this interpretation known in Second Temple times? (Genesis — and I’m departing from the Shinan and Zakovitch’s book here — is considered by some scholars to have been of very late composition, even as late as the second century BCE.)

So despite the vagueness and ostensibly virtual innocence of Ham’s “sin” (peeking at his naked father) in the Genesis account, the rabbis recognized that there was something more sinister just below the surface (the Midrash Genesis Rabbah 51:8).

The Unspeakable is Spoken

They (the rabbis) went further. B. Sanhedrin 70a says the following:

“And he knew what his youngest son had done to him.” Rav and Samuel [differ]. One says that he castrated him, the other says that he sexually abused him.

Castration? Where did that come from?

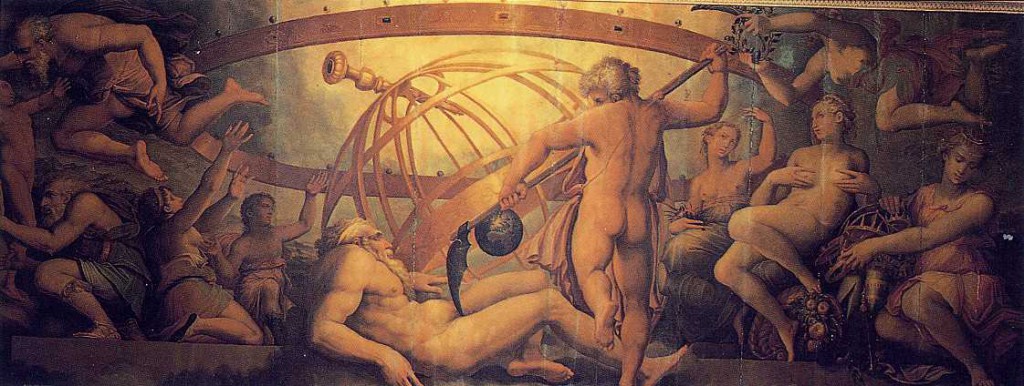

The neighbouring Phoenicians, Hurrites and Greeks all had myths of intergenerational conflict in which a son castrated his father or ruler. Philo of Byblos tells us the Phoenician god Kronos castrated his father Uranus with his own knife; the Hurrite god Kumarbi rebelled against the sky god Anu and replaced him as the ruler of the heavens, even biting his knee and swallowing his genitals. We know of the Greek myth of Kronos castrating his father Uranus, god of the sky.

Shinan and Zakovitch inform us that

what was told in the polytheistic nations surrounding Israel about the battles of gods was transferred, in the monotheism of the Bible, to the human realm. (p. 135)

It follows then, Shinan and Zakovitch explain, that the story of Ham and Noah developed in three stages:

First stage:

The mythic tradition of a son castrating his father in order to prevent his father from having more sons and “dilute the older son’s inheritance.” So the Midrash ha-Gadol to Genesis 9:25 says:

The Holy One, blessed be He, meant to issue four sons from Noah who would inherit the four winds of the earth. Ham said: I will castrate my father so that he will not produce a fourth son, in order that [this fourth son] will not share the world with us.

Rashi in the commentary says that the castration was performed “for inheriting the world.”

Now as Shinan and Zakovitch point out, an act of castration would leave some fairly obvious evidence for the sobered-up Noah to notice. It would also explain why Noah cursed Ham’s fourth son. If Noah could no longer have a fourth son then Ham’s fourth son was to be cursed.

Genesis Rabbah 36:7 explains

You prevented me from producing a youngest son who would serve me; consequently, the same man [you] will be his brother’s slave. . . . You prevented me from producing a fourth son, consequently I curse your fourth son.

Second stage:

The Pentateuch stepped back from documenting a castration upon a man who was elsewhere called “righteous” (Genesis 6:9). So Noah’s emasculation was replaced with a lesser evil, being raped by his son.

The “see nakedness” expression and the correlations with the Sodom narrative make this interpretation fairly clear.

Third stage:

Censorship finally sanitized the whole episode to infer that Ham was guilty of “seeing” his father naked and instead of covering his shame rushing to tell his brothers.

Interestingly the Bible retains an ambiguity here — as it does in many other narratives. The reader is not quite sure what the author intended. Alternative possibilities are always on the table.

Why Did God Want It In the Bible At All?

But why should such a tale enter Holy Writ at all? S and Z answer:

the story disparages two nations with whom ancient Israel was in contact, Egypt and Canaan, and calls for Israel’s utter separation from them. It is also possible that the story was . . . used to justify the Israelites’ conquest of the Land of Canaan. At least that is what is stated overtly in the Talmud: “The Canaanites said, The Land of Canaan belongs to us. . . . Geviha son of Persia said to them, . . . But [you are wrong, since] it is written in the Torah, ‘Cursed be Canaan a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.’ [Now:] if a slave acquires property, to whom does he belong, and whose is the property?” (B. Sanhedrin 91a)

S and Z also suggest a morality tale to warn against drunkenness.

In any event, we can, at the least, say that the obfuscation of the story’s objectionable contours was evidently enough to assure its place in the Bible. (p. 137)

I often wonder of such intriguing explanations how much of their account really is “true” and how much is owed to the wisdom of hindsight. Either way, it’s a plausible and interesting tale. It also underscores the point of Hector Avalos that the Bible is, or should be, an irrelevant book for any sort of moral guidance this day and age.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I read somewhere that the names match up to the myths in other cultures too. The elder god in these other stories had four sons though, not three (like Noah). The three son’s names match up a bit (like Hyperion=Ham, Japeth=Iapetus). The spare son in the original story is left over though, so Cronus is attached to Ham as Canaan. I think the non-Greek names match up way better, but from a quick scan of wikipedia I’m coming up short. This is only a small bit of supporting evidence to the obvious root of the story, as outlined above.

I don’t think the story has much to do with the forbiddenness of sodomy though. It’s far more to do with politics, and telling bad stories about your enemies ancestors is a good way to put them in their place. Lot’s story is very clearly a joke about neighbors, literally “Your father’s father’s mother was a father-lover!”

36 Thus were both the daughters of Lot with child by their father.

37 And the first born bare a son, and called his name Moab: the same is the father of the Moabites unto this day.

38 And the younger, she also bare a son, and called his name Benammi: the same is the father of the children of Ammon unto this day.

The story of Ham fits this mold perfectly. “The father of your father’s father was a father-lover!” Taboos on sodomy aren’t needed for the story to fulfill the same role (though the sodomy/rape angle was bowdlerized).

Thanks for reminding me of another work where I have read about this same interpretation — yes, Cronos who castrated his father had an older brother named Iapetus, the father of the Greeks. The association with Japheth is fairly clear. I’ll do another post on the extra info.

I just listened to part of an episode of the Geeks Guide to the Galaxy with Robert Price and Richard Carrier discussing the movie Noah. This topic comes up!

At 1:10:53 Price mentions some names, and that Japheth was Iapetus, and also the god of the Philistines. Baal-Hamon was the same god as Cronus in Greek. Price doesn’t cite his sources, and I’m not going to look into it more now.

Except Wikipedia says “Ham, son of Noah, was equated with “Jupiter Ammon”, i.e. the Egyptian god Amun.”

This is quite a mix of differing ideas. I’m not sure they can all be correct. However, the links between the Uranus/Titan story and Noah/sons story isn’t dented by the differing opinions on which names match up where.

I’d look into it more, but it doesn’t interest me enough. Just a fun curiosity.

I was going to post this comment on the next post, but I don’t want it mixed in with the weird ambiguous spamming. I don’t know how you put up with such commenters, Neil!

In Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic by Frank Moore Cross, p. 25:

And p. 26:

I would love to see this in works of Philo of Byblos and Diodorus Siculus and other inscriptions for myself, but till then I think it is safe to trust Cross is not telling us lies and that we can trust this link between Baal-Hamon and Kronos the Castrator of his father, and presumably an even more direct association between Ham and Kronos.

My point was that your next post (and my previous understanding) was that Iapetus was the god of the Greeks, and Robert Price said Iapetus was the god of the Philistines.

I am impressed! This passage has never made any sense, especially the cursing of Canaan for the sin of Ham. Your explanation is the first time that everything has come together for me. And seeing the story develop in three stages helps explain why it has taken so long to solve this puzzle.

I feel so blind not to have seen the chiasm involving the stories of Angels lusting after humans before the flood and humans lusting after Angels in Sodom and the stories of a child molesting a drunken parent (Noah and Lot). In your chart, I assume you meant to depict the story of Ham as “son -> father” instead of “father -> son.”

Yes, the error (father –> son) is in the original image.

I also think the “chiasm” description is a bit stretched. The Lot story strikes me more as one of those intertextual rewrites of the earlier narrative.

Adam “knew” Eve, and the men of Sodom wished to “Know” the angels. IIRC, the Hebrew word translated “Know” could indeed mean “to possess knowledge” but had the wider meaning of “to control, to put someone in a subordinate position”, and thus metaphorically “to be a dominant position sexually, to impregnate”.

So the argument goes that when Adam knew Eve, he wasn’t just depositing his sperm – he was keeping her down in a “wifely” subordinate role. And the men of Sodom weren’t concerned to rape the angels, but to humiliate them – possibly by rape but also by any other means.

This doesn’t suggest that Ham didn’t rape Noah, but it does suggest (to me) that the parallels you point out may be more complicated.

Interesting how the ancient Hebrews connected being dominant in society with going on top in bed, and we moderns talk about being “shafted” or “fucked” by our bosses.