Posting here a few more of my responses to questions that were raised on the BC&H forum about my stance on the Jesus mythicism question. (The first post in this series is Why I don’t see myself as a Christ Mythicist)

On making reasonable assumptions and seeing where they take us

On making reasonable assumptions and seeing where they take us

Is it reasonable to assume that the Gospel of Mark was received as about an actual person? Is it reasonable to assume that the Gospel of Mark as written around the 70s or 80s CE, in your mind? What makes an assumption reasonable when it comes to the Gospel of Mark?

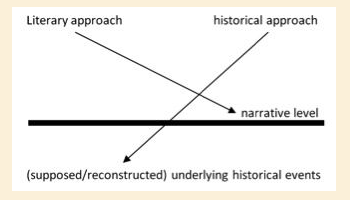

That’s not how valid historical inquiry works. Such a method can only produce speculative results. Not historical reconstruction.

According to the normative methods of dating documents the gospel of Mark could have been produced anywhere between 70 and 140 or even later CE. The only reason scholars prefer the earlier date is because of that mother of all assumptions, the presumption that the gospel’s narrative derives from a historical Jesus or events and they need/want the text to be as close as possible to that event so a proposed oral tradition chain does not lose too much in the process. And so the circle turns.

And that’s not even addressing the clear evidence that our form of the gospel is not what it was in the beginning.

What other historical inquiry works with “assumptions” that can never be corroborated from which they build their entire historical reconstruction? I suggest any that do are invalid.

Can you clarify your argument?

Is your argument that although 1st century CE Christians believed in a recently executed historical Jesus, we cannot tell if this Jesus really existed or not ? Or is your argument that we cannot tell whether 1st century CE Christians believed in a historical Jesus or not ?

I don’t argue for either. I leave behind any questions that arise directly or indirectly from the assumption that the fundamental plots of the gospel narratives or any of their narrative details are derived from real historical events. Such an assumption I find unsupportable given the absence of independent corroboration.

I think some biblical scholars work on the same principle: they study the Jesus in the gospels as a literary and theological figure. The question of historicity or otherwise simply does not arise. It is not a question that the sources enable us to explore.

Further, the question assumes the existence of a certain group (“Christians”) at a certain time (1st century CE) that I suggest are derived from the assumption of a historical background to the gospel narratives. What are “Christians” in the question? How are they defined? What is the evidence for them and for existing in the 1st century CE? I am not denying that there are reasonable answers to such questions. Just seeking my own clarification.

(Even if we are relying upon Paul’s letters, I am not sure that even those support the assumption that Paul and his followers belonged to a separate “Christian” group distinct from “Judaism”.)

The best I think we can say is that we have narratives about an executed Jesus (whether “recent” from the time of writing we cannot say with any confidence) and the historian needs to work with these, seeking to understand the nature of these narratives and explanations for their origins and the functions and influences they served. As for what certain people at certain times “believed”, that sounds to me like a very thorny question that will require a reliance upon more than the narratives themselves.

The letters of Paul are another set of documents that give rise to their own questions. The important thing, to me, is to study these questions without introducing traditional assumptions.

Is Matthew trying to squash rumours about the empty tomb?

Do you think Matthew 28:13-15 (if written in 1st CE) could be a actual response against the Jews of 1st CE who believed Jesus body was taken by his disciples after being crucified and thus evidence of historicity?

“Matthew” is writing a story. It’s a story. It could also be an actual response to Jews of the first century etc, but we would need to have independent evidence to support that interpretation. I don’t know how we can say that such a view (that it is an actual real-life response etc) is part of a historical record.

It is dangerous to use the Matthew narrative as evidence that Jews at the time were saying that Jesus’ body had been stolen. In fact, I don’t see how it can be justified by valid historical methods. Of itself, the story reads just like the ending of a Hans Christian Anderson tale that assures children that the shoes or some trinket can be found “to this very day” beneath a certain tree in a certain forest. It adds a teasing touch of verisimilitude.

(As a commenter wrote on my blog just a few hours ago, Matthew also seems to be teasing readers with a call for them to go and speak to witnesses of all the dead who rose out of their graves at the time Jesus died.)

It is just as reasonable to explain Matthew’s story of the bribery of soldiers as an attempt to tidy up a loose end in Mark’s narrative. And a far more parsimonious explanation that postulating all the variables that need to be introduced to support historicity.

Besides, what if the gospel were not even written until the mid-second century? Would there be such a concern for explaining away a historical event a century earlier? We simply don’t know when Matthew was written.

So am I a Jesus Mythicist?

My answer to that question is that I see no evidence comparable to the evidence we have for other known historical persons so as far as I am concerned the question is irrelevant. We cannot assume that he did exist. And I don’t assume he existed. If I were to think there was such a historical person then I would need to be shown clear evidence comparable to the evidence we have for other known historical persons.

For an example of what I mean by a proof-text argument and why I believe it is worthless see Thinking through the “James, the brother of the Lord” passage in Galatians 1:19.

Merely trying to argue a point by apologetic proof-texting is not going to cut it. Historians don’t do simplistic proof-texting; at least not “real historians”. They evaluate the evidence, its provenance, its context, its agenda, before they draw conclusions from it.

We can only work with the evidence we have, and if the ultimate goal of New Testament studies is to understand the origins of Christianity, then the literary Jesus is all we have and the only one we can work with.

(The epithet “mythicist” has become too emotionally charged. Academically, though, there is no need. Many critical scholars acknowledge that the Jesus of the gospels is surely literary and mythical. More biblical scholars are doing a new type of literary analysis on the gospels. It ought to be quite possible, at least in theory, for believers in a historical Jesus and for those who don’t believe there was a historical Jesus to discuss, argue, debate, explore and research the evidence together — as long as all are agreed that the evidence is the written documents we have and not some imaginary constructs that see the figures of the narrative take on a life of their own independent of those texts.)