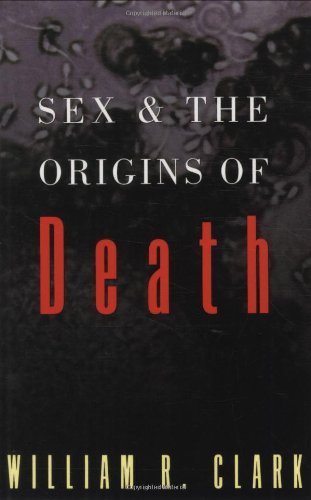

Recently, I was researching and preparing for the fourth chapter of the most recent Memory Mavens post. I wanted especially to resurrect, and then dismiss, Albert Schweitzer’s characterization of William Wrede’s work as “thoroughgoing scepticism.” I had already touched on this subject back in 2012 in our series on the Messianic Secret.

At the time, I quoted Wrede himself in his defense of reasonable skepticism.

To bring a pinch of vigilance and scepticism to [the study of Mark’s Gospel] is not to indulge a prejudice but to follow a clear hint from the Gospel itself.

In order to explain and defend Wrede’s method it seemed reasonable to me to compare it to Schweitzer’s (as Schweitzer himself had done, over 100 years ago). But then a funny thing happened. Try as I might, I could not find a single reference to “thoroughgoing scepticism” in the 2001 Fortress Press edition of The Quest of the Historical Jesus.

One of our shibboleths is missing

That seemed more than a little odd. Here is a catchphrase, set in stone within the hushed and hallowed halls of NT scholarship, and yet it was missing in action. Where had it gone? When did it leave?

The paper portion of my library, almost all of it, is miles away from me in a storage facility, so I’ve had to rely on electronic versions of Geschichte der leben-Jesu-forschung. The 1913 edition stored at Hathi Trust is in the public domain, and you should be able to read it, no matter what your country of origin is. (Sometimes Hathi Trust limits viewing to IP addresses from the U.S., because of unsettled copyright issues.)

As you probably already know, the first edition, in German, hit the streets in 1906, and it made a fairly big splash. NT scholarship in the English-speaking world took an immediate interest, which only grew when an English translation became available in 1910. Wrede’s The Messianic Secret would have to wait 60 more years. K. L. Schmidt’s Der Rahmen der Geschichte Jesu is still waiting.

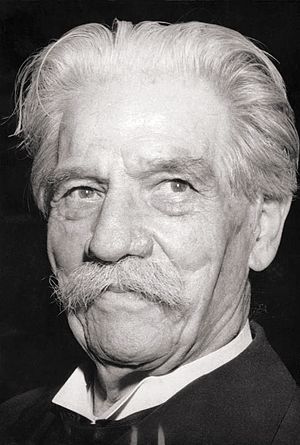

In the first edition, Schweitzer pokes Wrede in the eye with the title of chapter 19: “Thoroughgoing Scepticism and Thoroughgoing Eschatology.” Anglo-American scholars were delighted to see Wrede’s troubling thesis dispatched by such a towering, highly respected, intellectual figure. Who could ask for more?

Digging for nuggets, but not too deeply

Of course, Schweitzer’s magnum opus is, other than the Bible itself, the ultimate quote mine for English-speaking biblical scholarship. Certainly, no other modern work is so frequently quoted yet so rarely read. The Quest quickly became an indispensable quarry for scholars who are far too busy to read Reimarus, Strauss, Renan, or Wrede. Half-hearted, indifferent, indolent excavators have continued even into the late 20th and early 21st century, as this simple Google Books search demonstrates.

Consider the following examples: Continue reading “When Schweitzer Changed His Mind and Nobody Noticed”