The classical Greek myths related to the founding of the colony of Cyrene in North Africa (Libya) are worth knowing about alongside the biblical narrative of the founding of Israel. This post is a presentation of my understanding of some of the ideas of Philippe Wajdenbaum found in a recent article in the Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament, and that apparently epitomize his thesis, Argonauts of the Desert.

My recent post drew attention to the following mythemes in common to both the Phrixus and Isaac sacrifice stories. I’m not sure if my delineation of them is guilty of slightly blurring the edges of a strict definition of a mytheme, but they are certainly common elements.

- the divine command to sacrifice one’s son

- real in the case of Isaac,

- a lie in another in the case of Phrixus – P’s stepmother bribed messengers to tell the father the god required the sacrifice

- the father’s pious unquestioning submission to the command

- last-minute deliverance of the human victim by a divinely sent ram

- direct command to the father in the case of Isaac

- direct command to the sacrificial victim in the case of Phrixus

- the fastening of the ram in a tree or bush

- before the sacrifice of the ram in the case of Isaac

- after the sacrifice of the ram in the case of Phrixus

- the sacrifice of the ram

- as a substitute for Isaac

- as a thanksgiving for Phrixus

What is significant is that these narrative units in common to both stories exist at a level independent of the particular stories. They can be inverted and reordered to create different stories.

The question to ask is: Are these units similar by coincidence or has one set been borrowed from the other?

That particular detail about the ram in the tree or thicket is certainly distinctive enough to justify this question in relation to the whole set.

Firstly, given that it is no longer considered “fringe” (except maybe among a large proportion of American biblical scholars where the influence of ‘conservative’ and even evangelical religion is relatively strong) to consider the Bible’s “Old Testament” books being written as late as the Persian or even Hellenistic eras, and given the proximity of Jewish and Greek cultures, the possibility of direct borrowing cannot be rejected out of hand.

Secondly, the chances of the Jewish story of the binding of Isaac being influenced by the Greek myth is increased if both stories are located in a similar structural position within parallel narratives.

Both near-human sacrifice narratives serve as the prologues to larger tales of:

- divine promises of a land to be inherited by a hero’s descendants

- a special divinely chosen people

- a pre-arranged time schedule of four generations before the land would be inherited

- deliverance through a leader who initially protests because he stutters

- an additional delay because of human failure to hold fast to a divine promise

- a wandering through the desert with a sacred vessel

- guiding divine revelations along the way

Not only are both tales of escape from human sacrifice prologues to these larger comparable narratives, but they also serve as a reference point in both. They hold the respective longer stories together by serving as the origin point of the divine promises that guide the subsequent narratives of journeying to a promised land, and that origin point is referenced by way of reminder throughout the subsequent narratives.

The Biblical narrative is about much more than the way the children of Abraham inherited the land of Canaan, and here is where Philippe Wajdenbaum, in his 2008 doctoral thesis Argonauts of the Desert — Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible, draws attention to the extensive similarities between Plato’s writings and the Bible’s narratives. Both contain a general flood being the beginning of a new era in civilization, with a patriarchal age following, the rise of cities and kingship, and the development of laws and a description of an ideal state. The laws in the Pentateuch are often remarkably alike the laws proposed by Plato:

- laws that require a central religious authority,

- of a need for pure bloodlines (especially for priests),

- laws that condemn homosexuality, witchcraft, magic,

- laws of inheritance, boundary stones,

- laws allowing slaves to be taken from foreign peoples only,

- laws against the need for a king,

- laws governing involuntary homicide,

- laws regarding rebellious children,

- laws against usury, against taking too much fruit from one’s fields,

and quite a few more, and often found listed in the same order between the Greek and Hebrew texts.

The ideal state, moreover, is divided into twelve lots of land given to twelve tribes. The king, it is warned, is subject to the vices of love, and this will lead to oppressive tyranny. One might think here of the sins of David and Solomon.

Wajdenbaum applies the structural analysis of myths as developed by Claude Lévi-Strauss to the Bible, and one can see his coverage is much more extensive than can be covered in a few blog posts. Here I am focussing only on structural place of the Phrixus/Isaac “sacrifices” in their respective wider narratives.

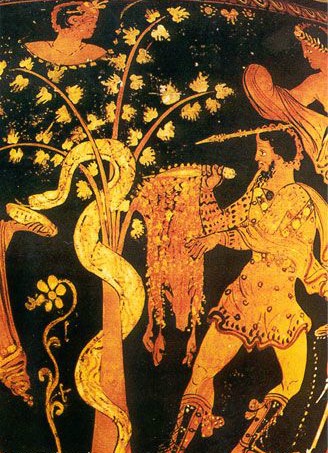

The Phrixus episode serves as the introduction to the adventures of Jason and the Argonauts, and this set of adventures functions as an explanation of the founding of the Greek colony of Cyrene in North Africa (Libya).

The Argonaut epic and the Bible narrative

I had earlier written a series of six posts on resonances between the Argonautica as told by Apollonius of Rhodes (they are found by starting at the bottom of this Argonautica archive) but this post is addressing Wajdenbaum’s thesis.

The full Argonaut epic is found in Pindar’s Fourth Pythian Ode. It had earlier been referenced in Homer’s Odyssey, XII, 69-72, in Hesiod’s Theogany, 990-1005, and in Herodotus (the foundation of Cyrene and the interrupted sacrifice of Phrixus). Euripides wrote two plays titled Phrixos, now lost to us. And of course Apollonius of Rhodes wrote the epic poem in imitation of Homer, The Argonautica.

The main sources for this epic relate it to the founding of Cyrene. (Pindar’s ode is even dedicated to the king of Cyrene.) This compares with the early Bible narrative from Abraham to Moses relating to the settling of Canaan.

Jason, leader of the Argonauts, belonged to the same extended family as Phrixus, all being descended from Aeolus.

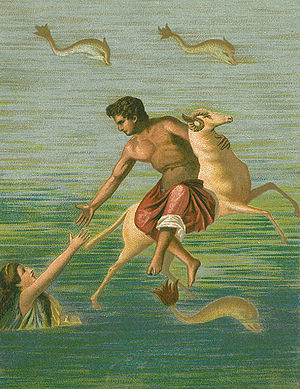

Zeus was angry with the descendants of Aeolus over the attempted sacrifice of Phrixus by his father, and to appease his divine wrath Jason embarked in the Argo with a band of followers (the Argonauts) to retrieve the golden fleece. (This was the fleece of the ram that had saved Phrixus at the last moment from being sacrificed.)

Triton, son of the sea-god Poseidon, appeared in human form and gave one of the Argonauts, Euphemus, a gift of a handful of Libyan soil as a token of a promise that his descendants would return and colonize the land. Had Euphemus succeeded in keeping the soil to plant appropriately in his own home area, his descendants would have returned to colonize only four generations later. But since the soil was washed overboard and its particles landed on the island of Thera instead, seventeen generations would have to pass and Cyrene would have to be colonized by the descendants of the Argonauts after first settling in Thera.

This is the reverse of the order in which we read of the “sacrifice” and the promise in the Biblical narrative. There, Abraham is promised the land and afterwards prepares to sacrifice Isaac. The Argonauts seek to appease Zeus’s anger of the attempted sacrifice of Phrixus by retrieving the fleece of the ram that saved him, and the promise of the land of Cyrene for the descendants of the Argonauts is made afterwards.

Generations later, after the descendants of the Argonauts had settled on Thera, a direct descendant of Euphemus was commanded through the Delphic Oracle to lead his people to settle and establish Cyrene in fulfilment of the promise made at the time the Argonauts were retrieving the fleece of the ram that had saved Phrixus.

This descendant was known as Battus (a name that means “stutterer”). He argued against the divine command on the grounds that he was not a great warrior and that he had a speech impediment. But the Delphic oracle refused to listen to reason and made him do as he was told anyway.

Herodotus tells us that Battus ruled Cyrene for the familiar forty years.

We are reminded of the promise to Abraham that his descendants would settle in Canaan after four hundred years of slavery in Egypt. Egypt serves as a delaying detour on their way to their destiny as Thera was in the Greek myth.

God commands Moses to lead his people to Canaan by invoking his promise to give it to the fathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Moses at first refuses by pleading that he stutters. If Battus ruled the Argonauts for forty years, Moses (also once called a king and known as a king in Philo), led his people for forty years also.

This narrative structure joining Abraham to Moses echoes with accuracy the promise made to Euphemus and its fulfilment by his descendant Battus. Both Moses and Battus invoked their trouble speaking in order to avoid their divine mission and both ruled over their people during forty years. Therefore, the similarities between the interrupted sacrifice of Isaac and that of Phrixos appear as part of a similar narrative structure. It seems as though Abraham plays two different characters from the Greek epic: King Athamas who almost sacrificed his son (Phrixos) — an episode from the beginning of the epic; and the Argonaut Euphemus who received the promise of land for his descendants — an episode from the ending of the epic. The order of the episodes has been reversed. In the same way, the detail of the ram hung on a tree after the sacrifice in the Greek version appears inverted to the account of the ram stuck in the bush before the sacrifice in Genesis. (p. 134, my bold)

To repeat a few lines I quoted in my earlier post, but this time without the omissions:

Parallelisms must not be analysed in an isolated way, but one must try to find out the possible narrative structure that links the similarities together. In other words, the similarity between Phrixos and Isaac is not sufficient by itself to speculate about any possible borrowing. But, when placed in the wider framework of the epic of the Argonauts and the foundation of the colony of Cyrene, it allows us to question a likely influence of the Greek mythical tradition on the writing of the OT. (p. 134)

Philippe Wajdenbaum notes that his thesis supports the one advanced by Jan-Wim Wesselius’s in The Origin of the History of Israel: Herodotus’s Histories as the Blueprint for the First Books of the Bible that the narratives in Herodotus have influenced the biblical narrative.

But there is one significant clue thus far missing, Wajdenbaum remarks. What might the founding of a colony in Cyrene in Herodotus have to do with the settlement and kingdom established in Canaan by Israel? Wajdenbaum points to an answer:

We must investigate the writings of another famous Greek writer to find the description of a State meant to be a colony. A State that would be divided into twelve tribes and ruled by perfect god-given laws — the ideal State imagined by Plato in his Laws. (p. 134)

And that is the topic of future blog posts.

This post is based on a discussion by Niels Peter Lemche in

This post is based on a discussion by Niels Peter Lemche in  Two archaeologists, one Israeli (Israel Finkelstein) and one American (Neil Asher Silberman), have bizarrely managed to repackage a Taliban-like ancient biblical legal code into a modern enlightened expression of human rights, human liberation and social equality.

Two archaeologists, one Israeli (Israel Finkelstein) and one American (Neil Asher Silberman), have bizarrely managed to repackage a Taliban-like ancient biblical legal code into a modern enlightened expression of human rights, human liberation and social equality.