Continuing the series from Nur Masalha’s Expulsion of the Palestinians. . . .

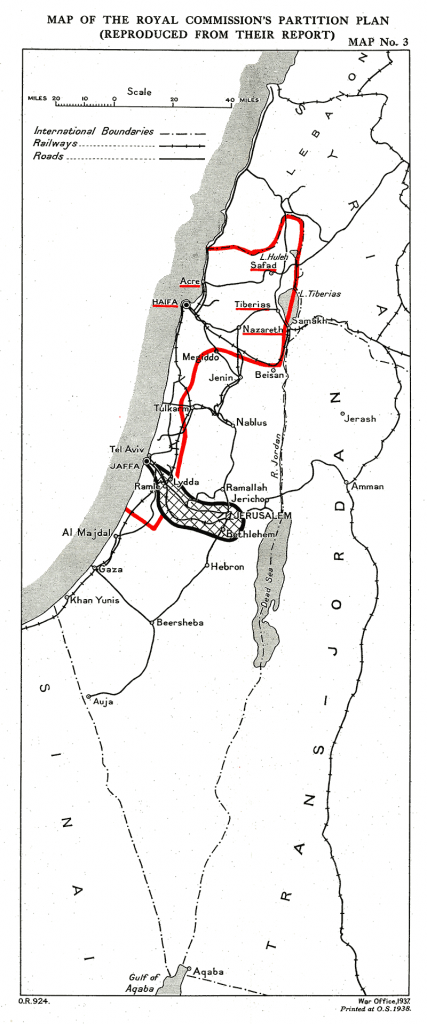

In the previous post we saw the initial reaction of the Zionist movement’s leadership to the Peel Commission’s 1937 recommendation that:

- Palestine be partitioned into two states, and

- that there be a transfer of 225,000 Arabs and 1250 Jews.

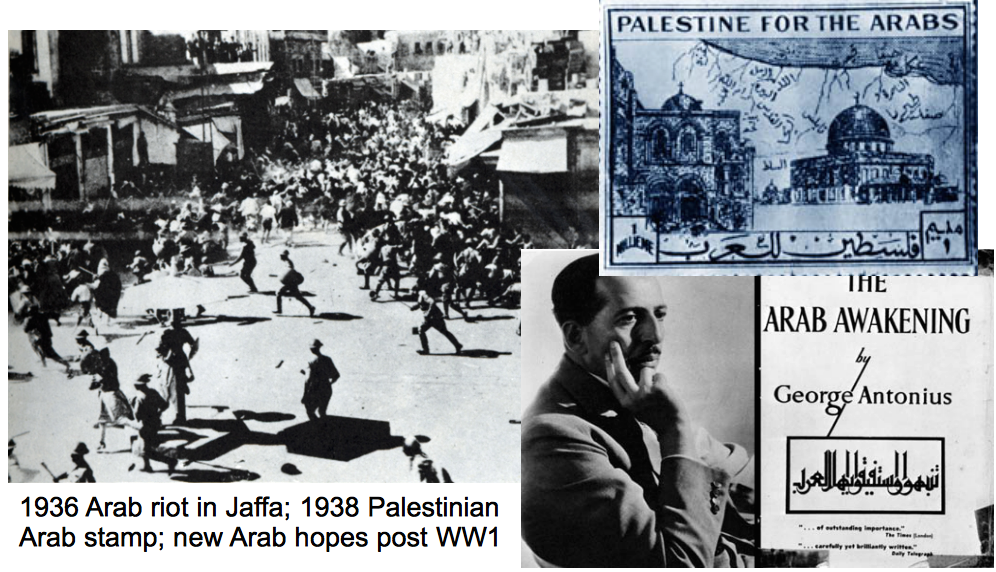

So far we have been looking at the words of Zionist leaders that were for most part hidden from the public arena. With the Peel Commission recommendations the question had to become public. Conventions had to be held. The rank and file needed to be consulted and won over. Fellow Jews who had more respect for the rights of the Palestinian Arabs also needed to be persuaded and won over.

The Peel report was debated by two of the highest organizations of Zionism. The final outcome was an emerging consensus that the two state proposal be rejected (the whole of Palestine should be given to the Jews) while the proposal for mass transfer of the Arab population was agreed upon by large majorities.

Wherever possible I have linked names to their Wikipedia pages so readers can assess the level of influence and standing each person had within the wider community at the time. It is important to know who many of these voices are but to provide details in the post itself would have risked losing the theme in a mass of web-page words.

The World Convention of Ihud of Po’alei Tzion

29 July – 3 August, 1937

Zurich

Better known as Poalei Zion, this was the highest forum for the dominant Zionist world labor movement. It was closely linked with the Mapai political party that dominated Israeli politics until 1968. David Ben-Gurion was a prominent leader in both organizations.

The proceedings of this convention were edited and subsequently published by Ben-Gurion in 1938. All quotations are from these proceedings.

Ben-Gurion and others in their respective presentations to the convention went to lengths to distinguish between the concepts of “transfer”, “dispossession” and “expulsion” and to stress the morality of such a transfer. “Transfer” was not the same as expulsion. The Commission’s report, Ben-Gurion made clear, did not speak of “dispossession” of the Arabs but only of “transfer”.

On 29th July he further pointed out that the Jews in Palestine had already been peacefully transferring Arabs through agreements with the tenant farmers and

only in a few places was there a need for forced transfer. . . . The basic difference with the Commission proposal is that the transfer will be on a much larger scale, from the Jewish to the Arab territory. . . . It is difficult to find any political or moral argument against the transfer of these Arabs from the proposed Jewish-ruled area. . . . And is there any need to explain the value in a continuous Jewish Yishuv in the coastal valleys, the Yizrael [Esdraelon Valley], the Jordan [Valley] and the Hula? (From the full report of the Convention, 1938, as are all quotations)

Eliezer Kaplan portrayed the transfer of Arabs as a something of a humanitarian act to make them at home among their own people:

It is not fair to compare this proposal to the expulsion of Jews from Germany or any other country. The question is not one of expulsion, but of organized transfer of a number of Arabs from a territory which will be in the Hebrew state, to another place in the Arab state, that is, to the environment of their own people.

Other speakers doubted the feasibility of transfer. Yosef Bankover, a founder of the Kibbutz Hameuhad movement and member of the Haganah regional command said:

As for the compulsory transfer . . . I would be very pleased if it would be possible to be rid of the pleasant neighbourliness of the people of Miski, Tirah and Qaiqilyah.

Bankover stressed to delegates that the Commission’s report implied that any transfer was to be undertaken voluntarily. Compulsion was against the intent of the report. Given that Bankover did not believe the British would risk further riots and bloodshed by enforcing Arab transfers. He rejected the report’s appeal to the Turkish-Greek transfers as a relevant case-study: these transfers were in effect by force and certainly under threat of being killed if they did not move, he said.

So the issues being debated and discussed were:

- the moral justification of transfer — (this was generally accepted)

- would forced transfers be practical?

- would forced mass Arab transfers be adequate compensation for the Jews giving up their aspirations to have the one and only state over all of Palestine?

- did the Peel Commission recommend transfer far enough afield? If the Arabs were only moved next door into Transjordan then the expansionist hopes of the Jewish state would be limited. Should not the Arabs be transferred to Syria and Iraq instead?

Continue reading “The Necessity for Mass Arab Transfer”

Hector Avalos is already renowned/notorious for The End of Biblical Studies. There he argued that the biblical texts are without any relevance today, or at least are no more relevant than any other writings from ancient times. Scholars who attempt to argue for the moral relevance of the Bible in today’s world, Avalos argues, do so by tendentiously re-interpreting selected passages out of their original contexts and arbitrarily downplaying passages that contradict their claims. Theoretically, Avalos reasons, one could take Hitler’s Mein Kampf and likewise focus on the good passages in it and insist they over-ride the bad ones, and that the negative passages should be interpreted symbolically and through the good sentiments we read into the better passages. No-one would attempt to justify the relevance of Mein Kampf by such a method. Yet Avalos points out that that’s the way scholars justify the relevance of the Bible in today’s world.

Hector Avalos is already renowned/notorious for The End of Biblical Studies. There he argued that the biblical texts are without any relevance today, or at least are no more relevant than any other writings from ancient times. Scholars who attempt to argue for the moral relevance of the Bible in today’s world, Avalos argues, do so by tendentiously re-interpreting selected passages out of their original contexts and arbitrarily downplaying passages that contradict their claims. Theoretically, Avalos reasons, one could take Hitler’s Mein Kampf and likewise focus on the good passages in it and insist they over-ride the bad ones, and that the negative passages should be interpreted symbolically and through the good sentiments we read into the better passages. No-one would attempt to justify the relevance of Mein Kampf by such a method. Yet Avalos points out that that’s the way scholars justify the relevance of the Bible in today’s world.