This post is a post-script to Why Joseph Atwill’s Caesar’s Messiah is “Type 2” mythicism

The synoptic gospels depict Jesus calling disciples to become “fishers of men”. The context indicates that Jesus wants them to gather people to Jesus, to have many Israelites repent and follow Jesus. The most obvious source for the image is Jeremiah 16:16. Look at it in context:

14 Therefore, behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that it shall no more be said, The Lord liveth, that brought up the children of Israel out of the land of Egypt;

15 But, The Lord liveth, that brought up the children of Israel from the land of the north, and from all the lands whither he had driven them: and I will bring them again into their land that I gave unto their fathers.

16 Behold, I will send for many fishers, saith the Lord, and they shall fish them; and after will I send for many hunters, and they shall hunt them from every mountain, and from every hill, and out of the holes of the rocks.

We know the authors of the synoptic gospels drew upon the “Old Testament” writings for many of their images and ideas.

Joseph Atwill, however, introduces an alternative explanation for the image of the disciples being called to fish for men in Caesar’s Messiah. Atwill sees “fishing for men” in the gospels as a cynical re-write of an actual battle on the lake of Galilee between Romans and Jews, and argues that the slaughter of Jews in that context was the original source for the concept of Jesus (a cipher for a Roman emperor) telling his followers to “fish for men”. Below I have copied his suggested source as Josephus narrates the battle along with my commentary on how it might relate to Atwill’s thesis. I have additionally raised a few questions about the narrative that I would be interested in following up — how much was Josephus fabricating the scene? The section is from the Jewish War 3:10

But now, when the vessels were gotten ready, Vespasian put upon ship-board as many of his forces as he thought sufficient to be too hard for those that were upon the lake, and set sail after them.

The battle on the lake of Galilee is about to begin. The Romans prepare in numbers to take on the Jews who had fled into the lake on their small boats.

[Question: Whose ships were the Romans boarding if the Jews had already fled in available ships?]

[Update 15th November 2018: My first question was based on the Whiston translation. Another translation speaks of “rafts” and I suspect that would be correct since it makes better sense in the context.]

Now these which were driven into the lake could neither fly to the land, where all was in their enemies’ hand, and in war against them; nor could they fight upon the level by sea, for their ships were small and fitted only for piracy; they were too weak to fight with Vespasian’s vessels, and the mariners that were in them were so few, that they were afraid to come near the Romans, who attacked them in great numbers.

The Jews who had fled in the ships were now isolated, unable to return to land because of the Roman forces there. Their ships were too small to take on the Roman forces, and they were too few in number, so they attempted to keep their distance from the Romans who were coming towards them in larger ships and greater numbers.

[Again, where did the Romans’ ships come from? It appears from the account that the Romans had larger ships than those of the Jews. If correct, did the Romans take time to build them? If they did, then could not the Jews in the smaller ships have sailed well away to some other part of the lake? Or were they completely surrounded? And if they were surrounded, then what need was there for the Romans to go to the trouble of building larger ships to pursue them? Why not simply let them die there?]

[Update 15th November 2018: As above — My first question was based on the Whiston translation. Another translation speaks of “rafts” and I suspect that would be correct since it makes better sense in the context.]

However, as they sailed round about the vessels, and sometimes as they came near them, they threw stones at the Romans when they were a good way off, or came closer and fought them; yet did they receive the greatest harm themselves in both cases.

They catapulted (presumably, rather than threw by hand) stones at the Romans. Some came closer to a Roman ship to engage in combat but only for the worse.

[Presumably the Romans in fact came up to the Jewish ships when they could catch them. Where did the stones that the Jewish forces threw come from? Did they gather them up before boarding? Did they have supplies for the light infantry slingers left over that they took with them?]

As for the stones they threw at the Romans, they only made a sound one after another, for they threw them against such as were in their armor, while the Roman darts could reach the Jews themselves; and when they ventured to come near the Romans, they became sufferers themselves before they could do any harm to the ether, and were drowned, they and their ships together.

Here we have an extension of the previous sentence. The significant difference of detail added this time is that Josephus tells us that those Jewish forces who made contact with the Romans in their ships were slaughtered. The Romans were able to sink their ships and fend off any Jewish attacker so that all the Jewish soldiers on board were killed by direct Roman action or indirectly by drowning.

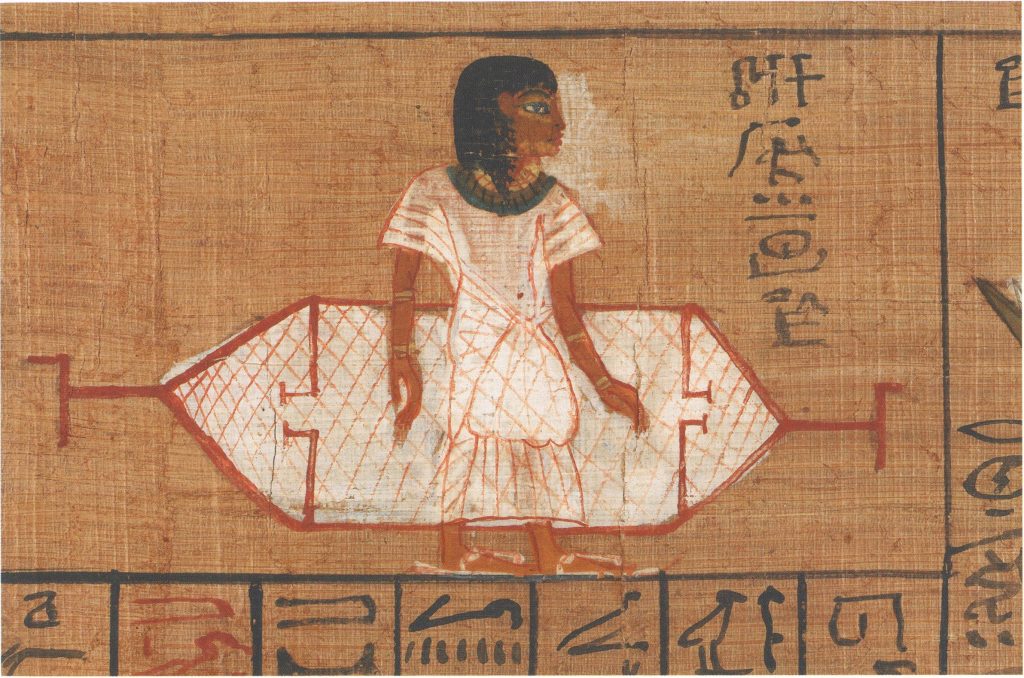

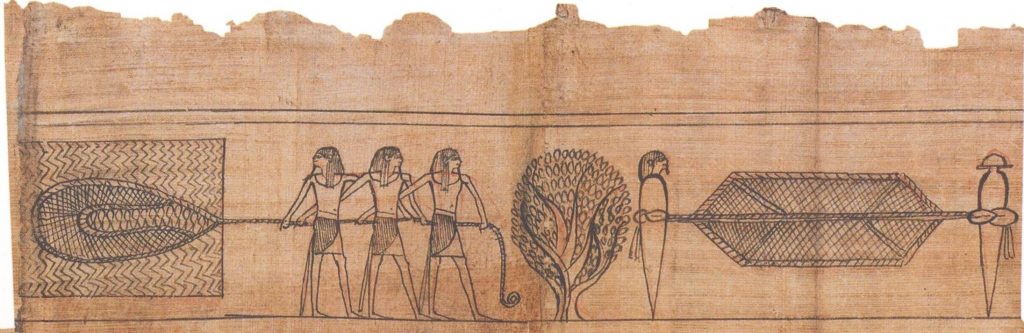

Here we finally come closest to any conceivable image of “fishing for men”. For the first time “men” (Jewish) are said to be in the water, but drowned. They are not “fished” for in any sense that I can imagine.

As for those that endeavored to come to an actual fight, the Romans ran many of them through with their long poles. Sometimes the Romans leaped into their ships, with swords in their hands, and slew them; but when some of them met the vessels, the Romans caught them by the middle, and destroyed at once their ships and themselves who were taken in them.

Again we have an expansion on the previous image. Sometimes the Romans soldiers were able to leap into the Jewish ships and begin their slaughter; other times the Roman ships rammed and broke up the Jewish ships.

And for such as were drowning in the sea, if they lifted their heads up above the water, they were either killed by darts, or caught by the vessels; but if, in the desperate case they were in, they attempted to swim to their enemies, the Romans cut off either their heads or their hands;

Here we continue the extended elaboration of detail of the contact between the Romans and Jews on the lake. We have seen how the Jewish forces were overwhelmed by the ramming Roman ships so that many were struggling to stay alive after their ship was wrecked and they were left in the water. Some of the desperate Jews swam towards whatever ship they could see only to find that they had approached a Roman ship. They were duly dispatched.

One can understand “fishers of men” referring to a gathering of people in a way fish are gathered in nets. And that’s the image that comes to mind in Jeremiah 16:16. But I suggest the image is far removed from Josephus’s account. Simply hacking at drowning remnant of a force doe not strongly bring to mind an image of “fishing”. Continue reading “Does Josephus intend to bring to mind an image of “fishing for men”?”

Like this:

Like Loading...