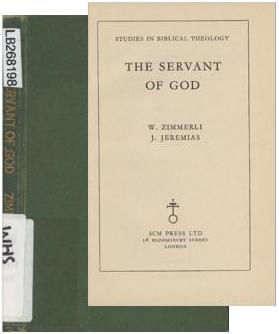

This post cites the tenth and final witness called by Joachim Jeremias in a 1957 book, The Servant of God. Thanks to helpful comments left by some readers I can say that the testimony of this particular #10 witness is disputed by scholars who argue that the rabbis of “Late Antiquity” responsible for interpreting Isaiah 53 were not influenced by any sort of anti-Christian bias. Maybe those critics are right. I hope to address in detail their arguments, either for or against, before the end of January 2019. Jeremias has been numbering his witnesses by the Greek alphabet and this final one therefore is the tenth letter of the Greek alphabet, kappa, or κ.

(κ) From the second century A.D. the history of Jewish exegesis of Isa. 53 is shaped increasingly by the opposition to Christianity.325

325 The rich material concerning the anti-Christian apologetic and polemic of Judaism in the first centuries has not yet been exhaustively dealt with.

In other studies of Jewish writings among biblical scholars (especially since 1967) there appears to have been a trend to undo negative perceptions of the Jewish past (the “rehabilitation of Judas” being one of the more distinctive examples) so I wonder if the “anti-Christian apologetic and polemic of Judaism” in the past has ever been “exhaustively dealt with”. If readers know what I don’t then I trust someone will inform me.

Jeremias outlines what he saw as Jewish efforts to remove earlier messianic associations from Isaiah 53:

This process begins by the avoidance of the description of the Messiah as ‘servant of God’ and ‘the chosen’, which the pseudepigraphic writers had used without embarrassment (cf. p. 50 and n. 262), and also of the title ‘son of man’,326 and ‘Jesus’, which had become a nomen odiosum (cf. TWNT, III, 287,20 ff.). From the end of the second century the apologetic method of changing the text327 and of tendentious interpretation was seized upon in translating Isa. 53, in order to dispose of passages which were of use to Christians in their text proofs. This polemical method is used especially in Targ. Isa. 53 (cf. pp. 66 ff.).

326 As distinct from Eth. En. it is lacking in Slav, and Heb. En. and in the whole of rabbinic literature (S.-B., I, 959; there is also the apparent exception J. Taan. 2, 1 [65b], 60).

327 For an example of the change in the Greek text see p. 65 and for an example of the change of the Aramaic text see n. 296; by the change of יפסיק (Targ. Isa. 53.3) into יפסוק , a statement about suffering is transformed into one about glory.

328 Fischel, 66, n. 67: *Probably the not very frequent use of 42.1 ff.; 50.4 ff., and 52.13 ff. in the Midrash is occasioned by the great significance of these texts in Christian exegesis.’

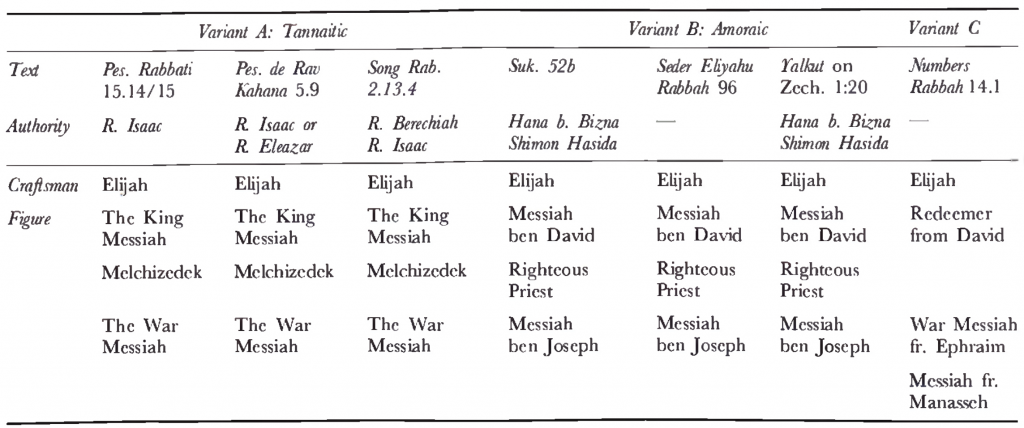

A similar mode of apologetic is used by R. Simlai (circa A.D. 250), who applies Isa. 53.12 to Moses (see n. 329). As far as possible, however, Isa. 42.1 ff. and 53 are not used at all.328 Indeed, it seems that messianic interpretations of Isa. 53 were excised whenever occasion served; in several instances there is at least a suspicion of this sort (cf. n. 313). These observations are very important for our judgement of late Jewish exegesis of Isa. 53. The widespread conclusion, that the relative infrequency of messianic interpretations of Isa. 53 in late Judaism shows that the latter was not acquainted with the idea of the suffering Messiah, does not do justice to the sources; for it ignores the great part which — very understandably — the debate with Christianity played in this question.

There is a certain silence in the rabbinic literature that Jeremais finds especially telling. In all biblical references to death — whether of an executed criminal, a high priest, the martyrs, the righteous, even children — rabbinic literature in the first thousand years finds a space to associate the death with an atoning power; there is only one exception, Jeremias claims, and that is the death of the servant in Isaiah 53. Such special treatment of Isa. 53 (in contrast to other atoning death interpretations) appears to suggest an effort to suppress or deny earlier understandings that may have been partly responsible for Christian views. Continue reading “The 10th Testimony for a Dying Messiah Before Christianity (7)”