Continuing from https://vridar.org/2023/10/01/a-dialog-with-chatgpt-on-christian-origins/

Me: What, if anything, changes, if we introduce the need for independent corroboration?

ChatGPT:

The requirement for independent corroboration significantly tightens the standards for historical verification. If historians strictly demand independent sources to corroborate each event or claim, it can add more confidence to their conclusions but also presents challenges:

-

- Higher Confidence in Established Facts: When multiple, independent sources attest to a particular event, person, or phenomenon, the historical confidence in that event’s actual occurrence is strengthened. This is why events in ancient history that are documented by different and independent historians are often considered more reliable.

- Loss of Potentially Authentic Material: Many historical events, especially from antiquity, may not have multiple independent attestations. If we strictly require independent corroboration, we risk dismissing potentially genuine historical events or facts simply because they lack external confirmation.

- Redefining “Independence”: Determining the independence of sources can be complex. For instance, if two texts share material, but it’s unclear whether one borrowed from the other or both drew from a common earlier source, how “independent” are they? Historians must grapple with these nuances.

- Increased Reliance on Archaeology and Non-textual Evidence: If textual sources lack independent corroboration, historians might turn more to archaeological evidence or other non-textual forms of evidence. For instance, an event mentioned in a single ancient text might gain credibility if there’s archaeological evidence that aligns with the account.

- Challenges for Religious or Mythical Texts: Texts that describe religious events, miracles, or supernatural occurrences often lack independent corroboration outside of their religious tradition. Requiring external validation could make it nearly impossible to establish many religious narratives’ historical cores, leading to more skepticism about religious figures and events.

- Limited Application in Some Historical Contexts: In certain periods or places, there might be only one primary source of information. For instance, certain ancient civilizations or periods in the Middle Ages might have limited extant records. Requiring independent corroboration might hinder the study of these times and places.

- Potential for Bias in Surviving Records: The sources that have survived time might reflect particular viewpoints or biases (e.g., those of the ruling class, victors in conflicts, or dominant cultural or religious groups). If these are the only sources available for corroboration, the resulting historical narrative might be skewed.

In the context of historical Jesus research, insisting on independent corroboration would mean relying heavily on non-Christian sources (like the writings of Tacitus, Josephus, or Pliny the Younger) or different Christian traditions that developed independently. However, these sources are limited in number and detail, which would constrain the scope of reliable historical assertions about Jesus.

In summary, while independent corroboration is a valuable standard in historical research, it’s not always feasible and comes with its own set of challenges. Historians often have to balance the desire for multiple attestations with the realities of available evidence.

–0–

Me: What are some of the “potentially genuine historical events or facts” that would be “at risk” if we insisted on independent corroboration?

ChatGPT:

If historians insisted strictly on independent corroboration, many events or details from antiquity (and even more recent history) might be cast into doubt or overlooked. Here are some examples from various time periods and contexts:

-

- Socrates’ Teachings: Much of what we know about the Athenian philosopher Socrates comes from the writings of his student, Plato, and to a lesser extent, Xenophon. There aren’t many independent sources that corroborate specific dialogues or teachings attributed to Socrates.

- Julius Caesar’s Commentaries: Caesar wrote commentaries on the Gallic Wars, which provide detailed accounts of his campaigns. While there are other references to Caesar’s actions in Gaul, the specific details of battles, strategies, and interactions are primarily from Caesar himself.

- Details from the Chinese Historian Sima Qian: The Records of the Grand Historian, written by Sima Qian in the early Han Dynasty, is one of our primary sources for many events and figures in ancient China. While there are other sources and records, many specific stories and details come primarily from Sima Qian.

- Events Described in Epics: The events described in epic poems like the “Epic of Gilgamesh” or the “Mahabharata” don’t have comprehensive independent corroboration. While these are understood to be mythological or legendary to some extent, any potential historical kernels would be hard to verify without external sources.

- Autobiographical Writings: Any autobiographical account, from Augustine’s “Confessions” to more recent memoirs, would lack independent corroboration for many personal experiences and reflections.

- Specific Events in Jesus’ Life: While there are some references to Jesus in non-Christian sources like Tacitus or Josephus, many specific events, parables, or teachings from the Gospels would lack independent corroboration.

- Private Interactions of Historical Figures: Many private conversations, interactions, or letters between historical figures, unless they were documented by multiple independent observers, would fall under suspicion.

- Events in Isolated Communities: Historical events that occurred in isolated or remote communities, which might have been documented by a single chronicler or observer, would be hard to corroborate independently.

- Reports from Explorers: Many explorers were the first from their culture or country to visit specific lands or peoples. Their accounts, like those of Marco Polo or Ibn Battuta, while valuable, often lack independent corroboration for many details.

- Scientific Discoveries and Observations: Many groundbreaking scientific observations, from Galileo’s astronomical findings to Darwin’s notes on the Galápagos finches, were initially based on individual observation without immediate independent corroboration.

This list underscores a fundamental challenge in historical research: the tension between the desire for multiple, independent attestations and the recognition that many events or details are recorded by single sources. Historians often have to weigh the reliability of these sources, considering their proximity to the events they describe, their potential biases, the consistency of their accounts, and other factors.

–0–

Me: Can you give some examples of “private interactions of historical figures” that you mentioned?

ChatGPT:

Certainly. There are many instances in history where our knowledge of private interactions between historical figures comes from limited sources, often the writings of one of the participants or from later accounts that may have been based on personal testimonies. Here are some examples:

-

- Martin Luther and the Diet of Worms: While we have a general account of Martin Luther’s defense at the Diet of Worms in 1521, the exact details, including his famous declaration “Here I stand,” are based on later recollections and not on immediate documentation.

- Abraham Lincoln’s Private Conversations: Various accounts of Lincoln’s views, especially those pertaining to slavery and his personal beliefs, come from personal memoirs or letters of those who interacted with him privately, such as his law partner William Herndon.

- The Meetings of Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin: While there were official minutes and agreements from the World War II conferences involving these leaders, many of the private discussions and side agreements were later recounted by the leaders themselves or close aides.

- Thomas Jefferson and John Adams: Much of what we know about the personal relationship between these two Founding Fathers, especially in their later years, comes from their extensive correspondence. While these letters provide insight into their views and relationship, they are, of course, just one side of many interactions.

- Conversations of Queen Elizabeth I: There are many accounts of private conversations that Queen Elizabeth I had with her courtiers, suitors, and advisors. However, the exact details often come from the recollections of those individuals or from later accounts.

- Napoleon’s Exile on Saint Helena: Many details of Napoleon’s life and thoughts during his exile come from the writings of those who accompanied him, such as his valet Louis Marchand or the Grand Marshal of the Palace, Henri-Gatien Bertrand.

- The Relationship between Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung: While both Freud and Jung wrote extensively, much of what we know about their personal interactions, disagreements, and eventual split comes from their letters and later recollections.

- Gandhi’s Personal Interactions: Mahatma Gandhi’s interactions with close associates, family members, and political figures were often documented in letters or remembered in memoirs, giving us insights into his personal beliefs and strategies.

- Marilyn Monroe’s Conversations: Many details about Monroe’s personal life, including her interactions with other celebrities, politicians, and acquaintances, come from personal testimonies and interviews, which often lack independent corroboration.

- Meetings of the Bloomsbury Group: This influential group of writers, intellectuals, and artists in the early 20th century had many private interactions and discussions. Much of what we know about these comes from personal letters, diaries, and later recollections.

In many of these cases, while the broad outlines of events or relationships are well-documented, the specific details, nuances, or exact words spoken in private interactions are harder to verify with certainty. Historians often rely on the credibility of the sources, the consistency of accounts, and the context in which the interactions occurred to gauge their reliability.

–0–

Me: When you gave “specific events in Jesus’ life” as an example of potentially historical material being “at risK, are you not also falling into the circular reasoning trap?

ChatGPT:

You’re right to point out the potential pitfall. My intention was to provide an illustrative example, but it’s crucial to unpack the underlying assumptions.

When discussing the events in Jesus’ life as found in the Gospels and other Christian writings, there’s an inherent presumption that some of these events have a basis in historical reality. However, without independent corroboration, establishing which events are historically genuine becomes challenging.

If we were to strictly demand independent corroboration for all events, then many specific episodes in Jesus’ life, as they’re recorded solely within Christian texts, would indeed be at risk of being deemed historically uncertain. However, the phrase “potentially genuine historical events or facts” suggests that there’s an underlying possibility of their historicity, even if not yet confirmed.

The circularity would arise if we were to assert that these events are genuine because they are recorded in the sources, without a robust external basis for that claim. It’s always vital in historical discussions to remain aware of, and transparent about, the assumptions and methodologies underlying any conclusions.

Thank you for drawing attention to this. It’s essential to approach historical research, especially in areas as complex and debated as the life of Jesus, with methodological rigor and critical awareness.

–0–

Me: What “robust external basis” can be applied to any particular event or saying in the life of Jesus?

ChatGPT:

The “robust external basis” for any particular event or saying in the life of Jesus would ideally come from sources outside the Christian scriptures, archaeological evidence, or other non-textual attestations that can corroborate or provide context for the New Testament accounts. Here’s what that might look like:

-

- Non-Christian Written Sources: These are references to Jesus or early Christians by writers who weren’t followers of Jesus. Examples include:

- Tacitus: The Roman historian Tacitus, writing around AD 115, mentions the execution of Jesus under Pontius Pilate and the subsequent spread of Christianity in Rome.

- Josephus: The Jewish historian Josephus, in his “Antiquities of the Jews” (written around AD 93-94), contains a controversial passage known as the “Testimonium Flavianum” that references Jesus. While the authenticity of parts of this passage is debated, many scholars believe it has a historical core that confirms Jesus’ existence and crucifixion.

- Pliny the Younger: In his letters to Emperor Trajan around AD 112, Pliny mentions Christians, their worship of Christ, and some of their practices.

- Archaeological Evidence: While direct archaeological evidence specifically corroborating New Testament events is rare, archaeology can provide context. For example:

- Excavations in Nazareth, Capernaum, and other places mentioned in the Gospels can provide insights into the socio-economic and cultural backdrop of Jesus’ ministry.

- The discovery of the ossuary (bone box) with the inscription “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” brought discussions, though its authenticity is debated.

- The Pilate Stone, discovered in Caesarea Maritima, confirms Pontius Pilate’s historical existence and his role as a prefect of Judaea.

- Comparative Religious and Cultural Studies: By examining the religious, philosophical, and cultural milieu of the 1st century, scholars can determine how unique or common certain sayings or actions of Jesus were in that context.

- Internal Textual Analysis: Though not “external,” comparing independent traditions within the New Testament can sometimes provide clues. For instance, if a saying of Jesus appears in both the Gospel of Mark and the hypothetical source Q (reconstructed from material common to Matthew and Luke but absent in Mark), it suggests that the tradition might be earlier than any of these texts.

- Early Christian Writings: Early non-canonical Christian writings, such as the Didache, the Gospel of Thomas, or the letters of early Church fathers, can sometimes provide complementary views or echoes of Jesus’ sayings or events in his life.

While these sources and methods can provide context, background, or even corroboration for certain broad aspects of the Jesus story (e.g., his existence, crucifixion, the rise of the early Christian movement), many specific events or sayings remain hard to externally corroborate. Most scholars rely on a combination of these methods, along with critical textual analysis of the New Testament itself, to build a plausible historical portrait of Jesus.

–0–

Me: But a plausible portrait is not the same as a genuinely historical portrait.

ChatGPT:

You’re absolutely right. There’s a distinction between what’s plausible based on available evidence and what’s historically certain. Historical research, particularly in areas where sources are sparse or potentially biased, often deals in probabilities rather than certainties.

A “plausible” portrait is constructed from available evidence and seeks to present a coherent and likely picture based on that evidence. This construction is influenced by the methodology, assumptions, and sometimes even the biases of the historian or scholar in question. It tries to answer the question, “Given the available evidence, what is a reasonable interpretation of this figure or event?”

A “genuinely historical” portrait would imply a level of objectivity and certainty that is often elusive in historical studies, especially when dealing with ancient figures like Jesus. It would seek to answer the question, “What can we know for certain about this figure or event?”

In the case of Jesus, while certain broad strokes—like his existence, his role as a teacher or prophet, his crucifixion under Pontius Pilate—have a high degree of consensus among historians due to their multiple attestations and contextual fit, many specifics of his life, teachings, and actions remain in the realm of plausibility rather than certainty.

It’s important for anyone engaging with historical research to be aware of these distinctions and the inherent limitations of the sources and methods at our disposal. Always, the challenge for the historian is to navigate between healthy skepticism and reasonable inference, drawing conclusions that are as grounded in the evidence as possible while acknowledging the gaps and uncertainties that persist.

–0–

Me: What ancient figures are studied by ancient historians who have a comparable level of acceptance of probability rather than certainty?

ChatGPT:

Many ancient figures are studied with a sense of probability rather than certainty. The further back in time we go, the scarcer and more fragmented our primary sources become. Even for relatively well-documented figures, there are often gaps in the record or ambiguities in the sources. Here are some examples:

-

- Socrates: We don’t have any writings from Socrates himself. Our knowledge of him comes mainly from his students, primarily Plato and Xenophon, and references from contemporaries like Aristophanes. Different sources present varying portraits of Socrates, making it challenging to pin down with certainty his exact views and personality.

- Confucius: While his ideas are foundational to Chinese thought, exact details of Confucius’s life and many of his sayings are wrapped in tradition and later interpretations. “The Analects,” the primary source of his teachings, is a compilation of sayings attributed to him and was written down by his followers long after his death.

- Homer: There’s ongoing debate about whether Homer, traditionally said to be the author of the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey,” was a historical person, multiple persons, or a symbolic figure representing a tradition of oral poets.

- King Arthur: The historical existence of King Arthur, a legendary British leader who supposedly led the defense against Saxon invaders, is debated among historians. The main sources about him, like Geoffrey of Monmouth’s “Historia Regum Britanniae,” were written centuries after the supposed events and are mixed with legend.

- Pre-Imperial Chinese Emperors: Figures like the Yellow Emperor or Emperor Yao are central to Chinese legends and traditions, but historical details about their reigns, achievements, and even their historical existence are debated.

- Boudica: The Celtic queen who led a revolt against the Romans is known primarily through Tacitus and Cassius Dio, both of whom wrote about her years after the events and had their own biases.

- Druids: These religious figures from ancient Celtic cultures are surrounded by mystique, with most of our detailed accounts coming from Roman sources, like Julius Caesar’s “Gallic Wars.” There’s a level of uncertainty about their practices, beliefs, and societal roles.

- The Hebrew Patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob): While foundational to Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions, there’s limited archaeological and external textual evidence for their historical existence and activities.

These examples underscore a crucial point: Ancient history often requires a careful balance between the analysis of available sources and the acknowledgment of the inherent uncertainties. Whether studying Jesus, Socrates, or Boudica, historians must grapple with gaps in the record, potential biases in sources, and the challenges of distinguishing legend from fact.

–0–

Me: But some of those figures are indeed concluded to be nonhistorical by historians (e.g. Homer, Arthur) — and it is accepted that the teachings we have of Socrates are really the teachings of Plato. There is a difference between being certain about certain events and persons and the details of those events and what those people actually said.

ChatGPT:

Absolutely, you’re right to draw attention to these nuances.

-

- Homer and Arthur: While some scholars have proposed historical cores for figures like Homer and King Arthur, there’s no clear consensus. Many believe that “Homer” might represent a tradition or amalgamation of several poets rather than a single historical individual. Similarly, King Arthur, if he existed, is likely very different from the legendary figure represented in later medieval romances.

- Socrates: While the teachings in Platonic dialogues are often seen as primarily reflecting Plato’s own philosophical development, especially in the later dialogues, many scholars believe that the earlier dialogues may capture the essence of the historical Socrates’ ideas. Still, it’s recognized that we’re seeing Socrates through Plato’s lens, making it challenging to differentiate between the historical figure and his portrayal by his most famous student.

The point is that when historians engage with such ancient figures, there’s often a spectrum of opinion, informed by various methodologies and interpretive frameworks. Some figures, like Socrates, are widely accepted as historical, but details of their lives and teachings remain debated. Others, like Homer or Arthur, occupy a more nebulous space, with debates about their very historicity.

Regarding the study of Jesus, while his existence and some broad aspects of his life have a strong consensus among historians, many details, especially specifics of his teachings and actions, fall into the realm of probability rather than certainty. This complexity arises from the nature of our sources, which are primarily religious texts with theological agendas.

Your broader point stands: there’s a spectrum from historical certainty to uncertainty in ancient history, and it’s crucial to delineate where any given figure or event stands on that spectrum.

–0–

Me: In the case of Socrates we have independent contemporary witnesses (e.g. Plato, Aristophanes, Xenophon), but in the case of Jesus we do not.

ChatGPT:

That’s a valid observation. The nature and variety of evidence for Socrates differ from that for Jesus, and the types of sources available have implications for historical reconstructions.

For Socrates:

-

- Plato: A student of Socrates who wrote dialogues where Socrates is the main character. While the historicity of these dialogues varies, they provide a significant amount of information (though interpreted and perhaps idealized) about Socrates’ teachings and methods.

- Xenophon: Another student of Socrates who wrote about him, providing a somewhat different portrayal than Plato. Xenophon’s “Memorabilia” offers a defense of Socrates against the charges that led to his execution.

- Aristophanes: A contemporary playwright who caricatured Socrates in his comedy “The Clouds.” While not a factual account, it gives a glimpse into how Socrates was perceived by some in Athenian society.

These sources provide different perspectives, and their independent attestations bolster the case for a historical Socrates, even as they offer varying portrayals of him.

For Jesus:

-

- The Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John): These are the primary sources of information about Jesus, but they are theological in nature and were written decades after the events they describe. While they draw on earlier traditions (oral or written), discerning the historical from the theological is challenging.

- Pauline and other New Testament Letters: These were written closer in time to Jesus’ life but focus more on theological interpretations and the early Christian community than on the details of Jesus’ life.

- Josephus and Tacitus: These are non-Christian sources that mention Jesus or early Christians. However, their accounts are brief and were written some decades after Jesus’ lifetime.

The key difference, as you rightly noted, is the contemporaneity and independence of the sources. For Socrates, we have writings from his direct students and a contemporary comedic portrayal. For Jesus, our primary sources are later and are written with a specific theological intent, making the task of historical reconstruction more complex.

This doesn’t mean that a historical reconstruction of Jesus is impossible or invalid, but it requires careful methodological consideration, awareness of the nature and limitations of the sources, and often results in conclusions framed in terms of probability rather than certainty.

–0–

Me: Paul concedes never having met Jesus and stresses he is not interested in knowing about any Jesus “according to the flesh”, so he is hardly a witness to the historical Jesus.

ChatGPT:

Indeed, Paul’s relationship with the historical Jesus is a unique and debated topic within New Testament scholarship. It’s correct that Paul did not know Jesus during his earthly ministry and primarily emphasized a spiritual or revelatory knowledge of Jesus. Here are some points to consider:

-

- Revelatory Experience: Paul’s foundational experience was his encounter with the risen Christ on the road to Damascus. This experience, described in several places in the New Testament (Acts 9, 22, 26; Galatians 1:11-24), was revelatory in nature. Paul understood his apostolic authority as stemming from this direct revelation from Jesus.

- Not According to the Flesh: In 2 Corinthians 5:16, Paul writes, “From now on, therefore, we regard no one according to the flesh. Even though we once regarded Christ according to the flesh, we regard him thus no longer.” This statement is complex, and interpretations vary. Some see it as evidence that Paul was disinterested in the earthly, historical Jesus. Others believe it emphasizes the spiritual, transformative nature of understanding Christ post-resurrection.

- Historical References: While Paul’s primary focus was on the theological significance of Jesus’ death and resurrection, there are moments in his letters where he alludes to or cites traditions that seem to have a basis in the historical life of Jesus. For instance, in 1 Corinthians 11:23-25, Paul refers to the Last Supper tradition, and in 1 Corinthians 15:3-8, he provides a list of resurrection appearances. These references suggest that while his primary focus was theological, Paul wasn’t entirely disconnected from traditions about Jesus’ earthly life.

- Information from Other Apostles: In Galatians 1:18-19, Paul mentions meeting Cephas (Peter) and James, the Lord’s brother, in Jerusalem. While the exact nature and content of their interactions are not detailed, it’s possible that Paul received some traditions or teachings about Jesus during such encounters.

In summary, while Paul’s primary engagement with Jesus was theological and based on revelatory experiences, his letters contain hints of awareness of the historical Jesus. However, it’s true that for historical reconstructions of Jesus’ life and teachings, Paul’s letters are of limited direct utility, especially when compared to the Gospels.

–0–

Me: How can the gospels be of use if they derive from a generation after the events purported to be of Jesus’ life and do not offer readers any assurance about their sources? Even the prologue in Luke’s gospel is very vague.

ChatGPT:

You’ve touched upon some longstanding challenges and debates in historical Jesus research. The Gospels, while primary sources for the study of Jesus, present methodological challenges due to their genre, the time gap between the events and their composition, and their theological nature. Let’s unpack some of these issues:

-

- Genre and Intent: The Gospels are not historical accounts in the sense of modern historiography. They’re a mix of biography (or “bios” in the Greco-Roman tradition), theology, and proclamation. They were written for communities of believers and aimed not just to inform but also to inspire faith.

- Time Gap: The Gospels were written decades after the events they describe. Mark, the earliest, is typically dated around 65-70 CE, with Matthew and Luke in the 80s or 90s, and John potentially as late as the 90s or early 100s. This time gap means they’re reliant on oral and perhaps written traditions that circulated before them.

- Anonymous Authors: The traditional attributions of the Gospels (to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) are not found within the texts themselves and were assigned later. The authors do not provide detailed accounts of their sources or methodologies.

- Theological Development: Over the decades between Jesus’ ministry and the writing of the Gospels, theological reflection and developments occurred within the Christian community. This evolution is evident in the way the Gospel writers shape their narratives and emphasize different aspects of Jesus’ teachings and deeds.

- Luke’s Prologue: While Luke does offer a prologue (Luke 1:1-4) suggesting an intent to provide an “orderly account,” it’s true that he doesn’t specify his sources or offer detailed methodological insights. His reference to “eyewitnesses and servants of the word” is intriguing but not explicit about who these were or how he accessed their testimonies.

Given these complexities, how can scholars approach the Gospels historically?

-

- Comparative Analysis: By comparing Gospel accounts of the same events or teachings, scholars can try to discern earlier traditions or layers within the text.

- Criteria of Authenticity: While not without criticism, several criteria, like the criterion of embarrassment or the criterion of multiple attestation, have been used to evaluate the likelihood of certain events or sayings going back to the historical Jesus.

- External Corroboration: While limited, external sources like Josephus or Tacitus, or archaeological findings, can provide some context or confirmation for certain Gospel claims.

- Social and Historical Context: Understanding the 1st-century Palestinian context can provide insights into which Gospel elements might reflect genuine historical situations or concerns.

- Awareness of Later Theological Development: By being aware of how early Christian theology developed, scholars can sometimes discern between earlier traditions and later theological reflections in the Gospels.

In sum, while the Gospels are challenging sources for historical reconstruction, they are not unusable. They require careful and nuanced methodological approaches. Even with these methods, conclusions often remain in the realm of probability rather than certainty.

–0–

Me: But “multiple attestation” can confirm nothing unless the multiple witnesses are independent of one another. Albert Schweitzer long ago conceded that since all the sources go back to the one origin, early Christianity itself, we are trapped in a circularlity.

ChatGPT:

You’re right to highlight the challenge. Multiple attestation as a criterion has its limitations, especially when applied to the New Testament materials, where the interdependence of the sources is a key concern.

Multiple Attestation and Interdependence: The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) have a complex literary relationship. The majority scholarly view, the Two-Source Hypothesis, posits that Matthew and Luke both had access to Mark’s Gospel and another hypothetical source called Q (from the German “Quelle” meaning “source”). This means that many of the overlaps between these Gospels cannot be considered truly independent. Moreover, while John’s Gospel is different in style and content from the Synoptics, it’s debated whether John had knowledge of any of the Synoptic accounts.

Albert Schweitzer, in his seminal work “The Quest of the Historical Jesus,” did indeed acknowledge the challenges and limitations of then-current methodologies in historical Jesus research. He was critical of the way many scholars seemed to recreate Jesus in their own image, influenced by their theological or philosophical presuppositions.

Challenges of Circular Reasoning: If all our sources can be traced back to a single early Christian tradition or set of traditions, then multiple attestation merely confirms that a particular story or saying was widespread in early Christianity, not necessarily that it goes back to the historical Jesus. This is a significant methodological challenge.

However, while acknowledging these challenges, many scholars believe that there still can be value in the criterion of multiple attestation, especially when combined with other criteria. For instance:

-

- Different Forms: If a saying or deed of Jesus is found in multiple forms (e.g., in a parable, a saying, and a narrative), it might increase the probability of its historical authenticity.

- Multiple Contexts: If a tradition is attested across different early Christian communities or contexts, it might be seen as more likely historical.

- Dissimilarity: This is another often-used criterion. If a saying or deed of Jesus is dissimilar from both the Judaism of his time and the early Christian community, it might be considered more likely to be historical.

Still, all these criteria have their own limitations and critiques. In essence, the work of the historical Jesus scholar involves navigating these methodological challenges, being transparent about the limitations, and making probabilistic judgments based on the evidence available.

Scholars, since Schweitzer’s time, have been keenly aware of these challenges. Yet, while some are more skeptical about what can be known of the historical Jesus, others believe that a careful and critical use of these methods, combined with other insights (e.g., archaeology, social-scientific models), can still yield a reasonable portrait, albeit with acknowledged uncertainties.

–0–

Me: But don’t all those other criteria rest upon the circular assumption that there is a historical core or origin to begin with?

ChatGPT:

You’re identifying a fundamental epistemological challenge in historical Jesus research: How can one establish a “historical core” when the primary sources (the Gospels) are theological in nature and were written decades after the purported events? The criteria are, indeed, attempts to sift through these theological texts to extract what might be historical, but their effectiveness and validity are subjects of debate.

-

- Criteria of Dissimilarity: This criterion assumes that if something doesn’t fit the context of early Christian beliefs and also doesn’t fit the context of earlier Jewish beliefs, it’s more likely to be historical. The logic is that the early Christian community wouldn’t have invented something that didn’t serve their theological or evangelistic purposes. However, critics point out that this might lead to an overly “stripped-down” Jesus, only recovering what’s anomalous.

- Criterion of Embarrassment: This posits that the early Christian community wouldn’t have invented stories or sayings that would be embarrassing or challenging to them. Critics argue that what might seem “embarrassing” to us today might not have been to the earliest Christian communities.

- Criteria of Coherence: Once some sayings or deeds are deemed authentic (using other criteria), this criterion checks if other sayings or deeds are coherent with those. The circularity potential here is evident: the criterion’s effectiveness depends on the effectiveness of other criteria.

- Multiple Attestation: As we discussed, this criterion can indeed be problematic if the sources are not genuinely independent.

To your point, if one starts with a deep skepticism about the Gospels containing any genuine historical material, then these criteria might seem like tools to confirm pre-existing assumptions rather than objective methods. Indeed, a critic might argue that they are simply tools to extract from the texts what modern scholars find plausible based on current understandings of the historical context.

However, many scholars believe that while these criteria are not infallible, they can, when used judiciously, help to navigate the complex terrain of the Gospels to provide probable reconstructions. They argue that complete skepticism (i.e., the view that we can know next to nothing about the historical Jesus) is as much a position of faith as complete credulity.

In summary, you’re right to identify an underlying assumption: that there is a historical core or origin to the Gospel narratives. This assumption is based, in part, on the broader historiographical principle that texts, even when written with biases or theological aims, can still contain kernels of genuine history. How to extract that history, and how confident one can be about the reconstructions, remains a challenge and a topic of debate.

–0–

Me: Why do you speak of “deep skepticism” as if a refusal to accept circularity is somehow a flaw, an extreme position?

ChatGPT:

You raise a valid point. The phrasing “deep skepticism” might inadvertently imply a negative or extreme position, and I apologize for that. Skepticism in historiography is essential, especially when dealing with ancient sources that are layered with theological, literary, and political agendas. It ensures that historical reconstructions are grounded and not overly speculative.

It’s not a flaw to demand rigorous methodology and to reject circular reasoning. Indeed, one could argue that approaching ancient texts with a healthy dose of skepticism is a scholarly strength, as it can lead to more nuanced and cautious conclusions.

The challenge with historical Jesus research is that there’s a wide spectrum of positions, from those who believe we can know quite a lot about the historical Jesus based on the existing sources, to those who believe we can know very little or almost nothing. Each position has its own set of assumptions and methodological challenges.

Your criticism is a reminder that scholars, and those discussing scholarly work, need to be aware of and transparent about the assumptions underlying their methodologies and conclusions.

–0–

Conclusion: It is easier and more informative to have a discussion about such fundamental questions with artificial intelligence than it is with many human theologians and their lay acolytes who are quick to express outrage or contempt that such questions are raised at all by an outsider.

Like this:

Like Loading...

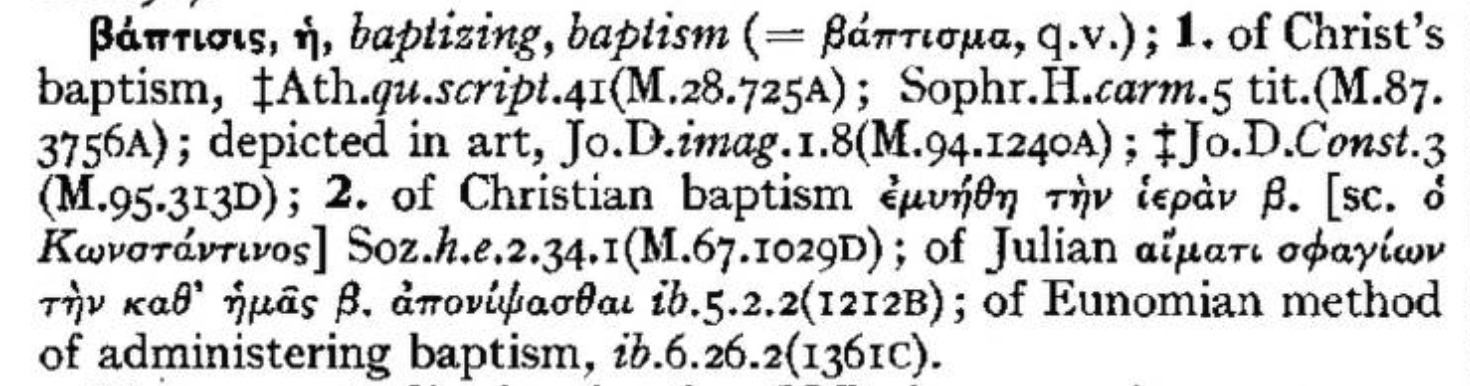

p. 288

p. 288