Thanks to Jim West I was informed of the public availability of a new article by the well-known New Testament scholar John S. Kloppenborg.

Kloppenborg, John S. 2017. “Disciplined Exaggeration: The Heuristics of Comparison in Biblical Studies.” Novum Testamentum 59 (4): 390–414. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685365-12341583.

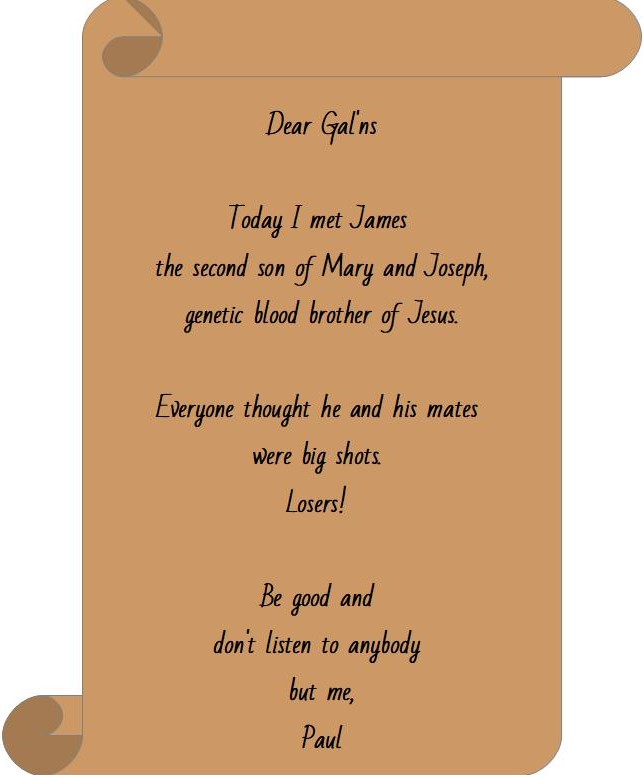

I think the article should always be cited whenever reference is made to Samuel Sandmel’s 1962 article warning of the flaws of uncontrolled “parallelomania“. Together they warn against either extreme.

Some quotations from Kloppenborg’s article (with the usual notice that formatting and bolding is mine):

By contrast, comparison in the historiography of early Christianity has had a peculiar history: comparisons were often employed either to establish the difference and, indeed, the incommensurability of Christian forms with anything in their environment; or, as Jonathan Z. Smith has observed, comparison was used to create “safe” comparanda such as the construct of “Judaism,” which then served to insulate emerging Christianity from “Hellenistic influence.” . . . .

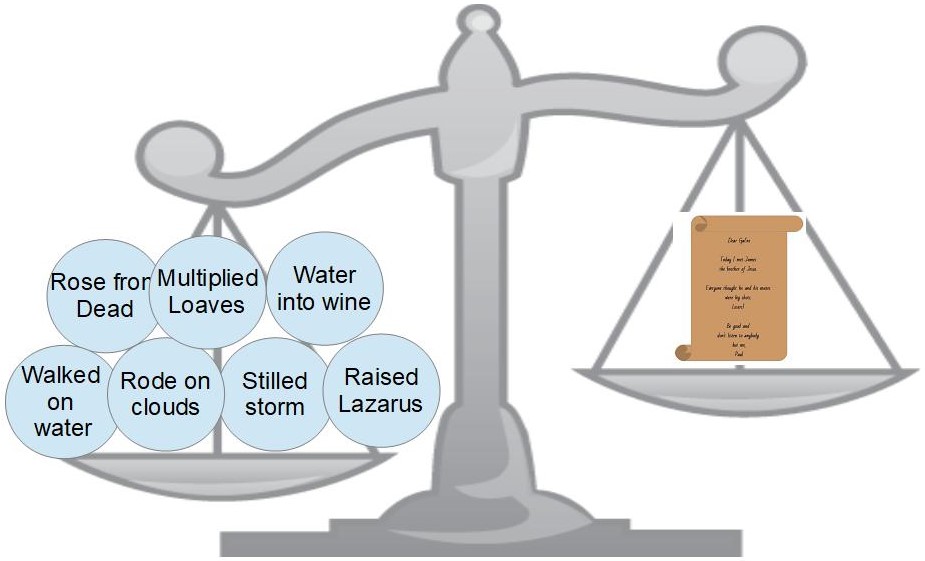

. . . . comparison in the study of early Christianity has often been used to assert its sui generis and incommensurable character. That is, comparison is invoked to rule out comparison or to limit it so that comparison becomes inconsequential. (p. 393)

Some readers will be aware of the work of the Jesus Seminar and the publications of John Crossan, Burton Mack and others pointing out similarities to Q and Cynic sayings.

On this hypothesis, the social postures evident in either the Sayings Gospel Q, or (for Crossan) in for the historical Jesus himself could be fruitfully compared with Graeco-Roman Cynicism. There was no claim that Q or Jesus were “influenced” by Cynicism, but instead that the social postures of Q (or Jesus) were “cynic-like,” in the sense that they constituted a radical deconstruction of the prevailing ways in which Galilean society constructed social and economic hierarchies, moral categories, and the very nature of piety. The reaction to this proposal was immediate and visceral. (pp. 394f)

And continues to this day, I notice.

No! No! No! went the reaction. There was no “archaeological evidence” of Cynicism anywhere in Galilee. Recalling the story that the reputed founder of Cynicism, Diogenes, set up his home in a bathtub (some say wine-cask) Kloppenborg wryly comments:

one wonders what could constitute archaeological evidence of Cynicism: bathtubs?

But K more pertinently notes the evidence of the tendentiousness of this reaction: Continue reading “Scholarly Protection of the Uniqueness of Christianity”