Multiple sources

Multiple sources

Matthew and Luke did indeed use Mark, but significant portions of both Gospels are not related in any way to Mark’s accounts. And in these sections of their Gospels Matthew and Luke record extensive, independent traditions about Jesus’s life, teachings, and death. . . .

But that is not all. There are still other independent Gospels. The Gospel of John is sometimes described as the “maverick Gospel” because it is so unlike the synoptic accounts of Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

Gospels continued to be written after John, however, and some of these later accounts are also independent. Since the discovery in 1945 of the famous Gospel of Thomas, a collection of 114 sayings of Jesus, scholars have debated its date. . . . [A] good portion of Thomas, if not all of it, does not derive from the canonical texts. To that extent it is a fifth independent witness to the life and teachings of Jesus.

The same can be said of the Gospel of Peter, discovered in 1886. . . .

Another independent account occurs in the highly fragmentary text called Papyrus Egerton 2. . . . Here then, at least in the nonparalleled story, but probably in all four, is a seventh independent account. (Ehrman, 75-77)

Within a couple of decades of the traditional date of his death, we have numerous accounts of his life found in a broad geographical span. In addition to Mark, we have Q, M (which is possibly made of multiple sources), L (also possibly multiple sources), two or more passion narratives, a signs source, two discourse sources, the kernel (or original) Gospel behind the Gospel of Thomas, and possibly others. And these are just the ones we know about, that we can reasonably infer from the scant literary remains that survive from the early years of the Christian church. No one knows how many there actually were. Luke says there were “many” of them, and he may well have been right. (Ehrman, 83)

We have a number of surviving Gospels—I named seven—that are either completely independent of one another or independent in a large number of their traditions. (Ehrman, 92)

Indirectly, then, Tacitus and (possibly) Josephus provide independent attestation to Jesus’s existence from outside the Gospels although, as I stated earlier, in doing so they do not give us information that is unavailable in our other sources. . . . As a result of our investigations so far, it should be clear that historians do not need to rely on only one source (say, the Gospel of Mark) for knowing whether or not the historical Jesus existed. He is attested clearly by Paul, independently of the Gospels, and in many other sources as well: in the speeches in Acts, which contain material that predate Paul’s letters, and later in Hebrews, 1 and 2 Peter, Jude, Revelation, Papias, Ignatius, and 1 Clement. These are ten witnesses that can be added to our seven independent Gospels (either entirely or partially independent), giving us a great variety of sources that broadly corroborate many of the reports about Jesus without evidence of collaboration. (Ehrman, 97, 140f)

. . .

A Single Source

A Single Source

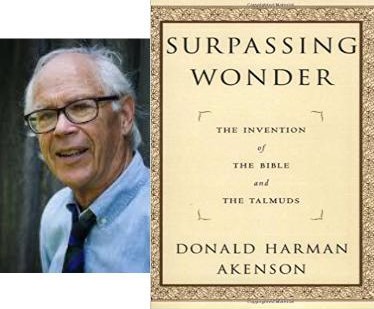

Significantly almost every scholar who pushes for the authenticity, and the early dating, of various extra-canonical items, does so with the argument that these texts were part of the core tradition of early Christianity: in other words, that they are not independent witnesses to the historical Yeshua. (Akenson, 552)

The Synoptic Gospels and the Gospel of John not alternative independent witnesses, but slightly variant editions of a single source: both are found within the Christian interpretative tradition and, as we have seen (Chapter Nine), this tradition required that for Yeshua of Nazareth to be come Jesus-the-Christ, he had to be identified as a Passover sacrifice. Thus, we have here a single tradition, not a multiply-attested set of historical observations. Emphatically, this does not mean that the single-source tradition is wrong, merely that it is not confirmed by the self-repetition of certain points within the Christian scriptures. (Akenson, 553)

Some scholars have suggested that cella in of the para-biblical books – such as the Gospel of Thomas or the Gospel of Peter – intermixed with ”Q” and Mark and the unique portions of Matthew and of Luke in the biblical equivalent of the primal soup from which all life is said to stem. Some few others throw into the stew a “Cross Gospel” which is an hypothetical document, said to underlie the Gospel of Peter. Just how far out of control this is, and unrelated to anything a professional historian would recognize as a testable hypothesis or as having probative value, is illustrated by the following summary of his own theory of the formation of the Gospels, put forward by John Dominic Crossan, one of the best-known of Roman Catholic biblical historian

The process developed. in other words, over these primary steps. First, the historical passion, composed of minimal knowledge, was known only in the general terms recorded by. say, Josephus or Tacitus. Next, the prophetic passion, composed of multiple and discrete biblical allusions and seen most clearly in a work like the Epistle of Barnabas, developed biblical applications over, under, around, and through that open framework. Finally, those multiple and discrete exercises were combined into the narrative passion as a single sequential story. I proposed. furthermore, that the narrative passion is but a single stream of tradition flowing from the Cross Gospel, now embedded within the Gospel of Peter. into Mark, thence together into Matthew and Luke, and thence, all together, into John. Other reconstructions are certainly possible. but that seems to me the most economical one to explain all the data.

– a strange brew indeed. (Akenson, 573)

[E]ven if one finds the heuristic-Gospel “Q” useful in understanding the evolution of the biblical text, it docs not constitute multiple attestation by independent witnesses of the sayings or deeds of the historical Yeshua. All the sayings are derived from a unitary source, the extant canonical scriptures, and just as the canonical scriptures are a single witness, so any hypothetical derivative from the canon is pan of the same single unitary source. To be blunt: one cannot obtain multiple independent attestation of the historical Yeshua simply by chopping up the “New Testament.” (Akenson, 574-5)

Compare Akenson’s point with Schweitzer’s:

Moreover, in the case of Jesus, the theoretical reservations are even greater because all the reports about him go back to the one source of tradition, early Christianity itself, and there are no data available in Jewish or Gentile secular history which could be used as controls. (See Schweitzer in context for full quote and variant translations.)

Akenson, Donald Harman. 2001. Surpassing Wonder: The Invention of the Bible and the Talmuds. New edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ehrman, Bart D. 2013. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne.

While doing a little background research on folklore and oral tradition, I happened upon something written by

While doing a little background research on folklore and oral tradition, I happened upon something written by