A book that concludes to assign the Epistle to the Galatians and the other main Pauline epistles to the second century requires, more than any other, a few words of introduction. Not that I believe that any preliminary remarks can remove the impression of bewilderment that such an undertaking must initially make on any theological reader, regardless of their direction. However, it is important to me to leave no doubt about the sincerity of my intention, and I hope to achieve this by explaining how I arrived at my view. (Steck’s opening words – translated – of Der Galaterbrief nach seiner Echtheit untersucht nebst kritischen bemerkungen zu den Paulinischen Hauptbriefen, or The Epistle to the Galatians examined for its authenticity along with critical remarks on the main Pauline letters, published in 1888.)

Steck described his university years and his arrival at the firm conclusion that the four main Pauline epistles (Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians and Galatians) expressed the purest thought of earliest Christianity. He had heard of the existence of sceptical views that discounted the authenticity of those letters but ….. in his own (translated) words:

Although I had heard doubts about the authenticity of these epistles, I only received the impression that there were also such oddballs among theologians who had to doubt even the sunniest clarity, and Bruno Bauer appeared to me as an unscientific tendentious writer whose audacity had not shied away from an attack on these most genuine monuments of early Christianity.

Bruno Bauer had such an unsavoury reputation that it took him some time before he was eventually led by circuitous routes to read the words of the devil for himself, and once he had done so….

Only then did I turn to Bruno Bauer’s critique of the Pauline epistles from 1852, which I had previously only known through references. Despite its facile argumentation and often offensive presentation to theological ears, I found in it much that was accurate and previously unnoticed, solidifying my view until it became a full conviction.

A few pages into his first chapter Steck added:

The criticism of Bruno Bauer has so far not been refuted by competent scholars, and although it is of such a nature that no one likes to deal with it, scientific necessity demands a closer examination, even if only to refute it thoroughly.

Ignored, but not refuted. A situation that has by and large continued through to today, unless I am mistaken.

I copy here a translation of Steck’s concluding statement of the findings of the detailed analysis of the preceding five chapters. The formatting is mine:

Consequently, the Epistle to the Galatians must be regarded as

- a literary product not of Paul himself, but of the Pauline school,

- presupposing the existence of the Epistle to the Romans and the two Epistles to the Corinthians.

Its dependency on these predecessors, particularly on the former, has become evident from a closer consideration of many individual passages, leaving little room for doubt. Of course, if the matter were merely that our epistle repeatedly contains expressions, phrases, entire sentences found in other major Pauline epistles, little would be proven. That can happen and, in itself, is not a sign of inauthenticity. It is quite natural for the same writer to use the same thoughts and sometimes expressions repeatedly as opportunities arise. . . . .

However, the matter is not that simple. The passages in our letter that prompted us to look for parallels in other letters were those

- where the context was lacking,

- where thought and expression did not seem quite natural,

- where one had to ask whether the previous explanations had all remained forced and contrived. . . .

(pp 147f)

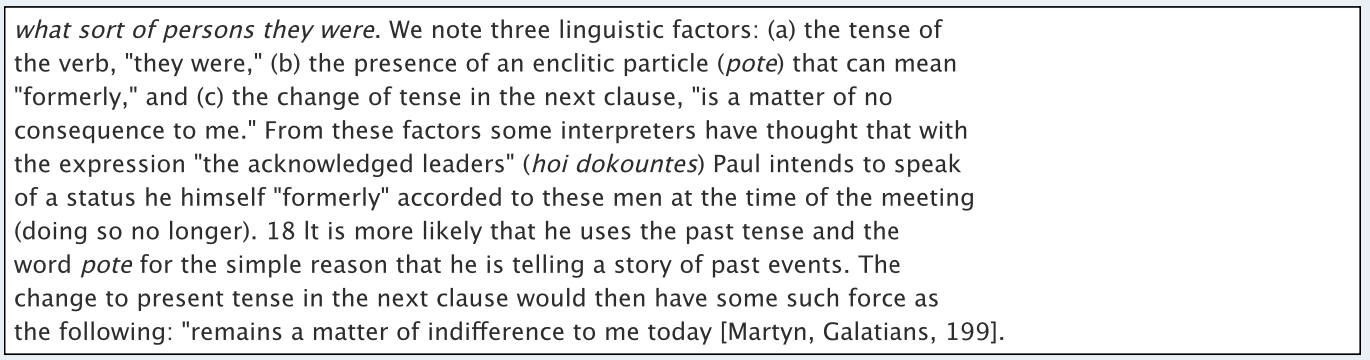

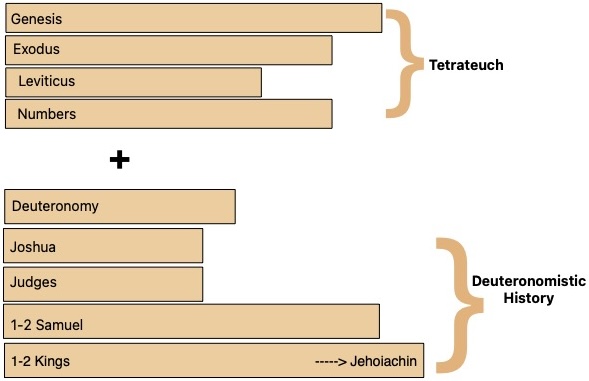

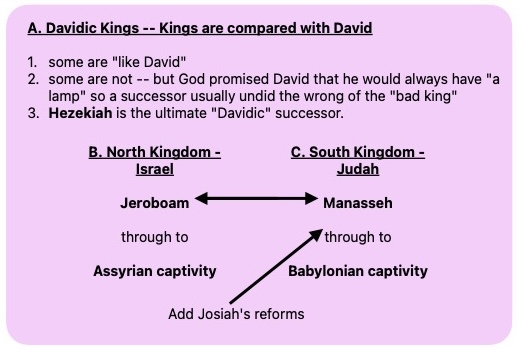

In short, obscurities of argument and puzzling loose ends in Galatians are clarified only when we turn (mostly) to Paul’s letter to the Romans. The author of Galatians presupposed a knowledge of the epistle sent to Rome. In Steck’s view, whoever wrote Galatians had either earlier written or certainly read and embraced the Romans tract and the two letters to the Corinthians. The corollary here is that the author further assumes that his primary audience of Galatians will understand his various points because they, too, are familiar with the other epistles. In the earlier chapters of Galatians where “Paul” sets out historical details from the time of his conversion to the time of his meeting with apostles in Jerusalem, the author was seeking to rebut the account in the Acts of the Apostles.

. . . [The author] addresses this letter as the purest expression of his spirit and opinion to the erring communities, a letter from which one should clearly recognize the Apostle’s actual stance towards Judaism. The letter would thus have been written not only long after the fall of the Jewish people and state (4:25) but also after the Acts of the Apostles. Since the latter writing cannot have originated before the beginning of the second century, as its acquaintance with Josephus proves for the Lucan writings in general, the Epistle to the Galatians is to be placed under the reign of Hadrian, and specifically after 120 AD.

(p. 148)

But how could it be so?

This view will undoubtedly be challenged by asserting that it claims the impossible. A letter as fresh and lively as the Epistle to the Galatians bears the stamp of the Pauline spirit too clearly for it to have been composed by a mere imitator. It is a work of a single cast and does not at all give the impression of a patchwork based on other letters. This objection is very understandable, and the perspective on the Epistle to the Galatians that underlies it was also long shared by the author.

. . . . One does not necessarily need to see in him a mere imitator; he could be a Pauline follower with an independent, sharply defined intellectual individuality who knows how to use the catchphrases of early Paulinism in a new, spirited way and to combine individual elements into a new whole. In such questions, one easily forgets that a letter merely attributed to Paul does not necessarily have to be the miserable work of an unoriginal imitator. If a significant, intellectually powerful personality stands behind it, the work will also bear its stamp despite the partial reliance on earlier material.

(p. 150)

In the second part of the book Steck examines all four major Pauline letters since if Galatians is not by Paul then the argument infers that the others are likewise not by a mid-first century author. To begin with, he analyzes the shared material among these four and demonstrates that it is Galatians that drew upon the others, and that Galatians was the last written and Romans the first. Steck then examines the evidence for the Pauline works drawing upon canonical gospel material. The evidence there is not overwhelmingly strong but in Steck’s view it is suggestive. Next, Steck sets forth the evidence for these letters drawing upon a knowledge of the works of pseudepigraphical writings (in particular the late first century/early second century Fourth Book of Ezra), and Philo and Seneca. If we accept the case for the epistles drawing on a knowledge of these works then we must date them to the very late first century at the earliest. Other arguments include overviews of patristic references to the Pauline writings — including the letters of Clement and Barnabas, the Shepherd of Hermas, the Didache, Justin Martyr, Marcion and other works.

We may even add a knowledge of the Ascension of Isaiah — courtesy of Roger Parvus’s studies.

I may post some of Steck’s evidence in detail in future posts but right now I am still in the process of digesting it all. I need more time to reflect.

I was intrigued to find one part of Steck’s thought running parallel with a certain notion of Christian origins that I had been exploring. Steck confronts the problem of finding an early gentile Christianity in Rome that existed quite independently from the synagogue.

Judaism and Christianity existed entirely separately in Rome at that time. This could not be the case if Roman Christianity had emerged from the synagogue. Thus, we are led to assume that Christianity in Rome emerged very early and somewhat autochthonously. The exclusive use of the Greek language in the Roman community until deep into the second century suggests that the roots of the oldest Roman Christian community lie not in the Jewish, but in the Greek colony of Rome. From this stratum of the population, the Christian doctrine gathered a circle around itself, as indicated in the 16th chapter of Romans, consisting largely of slaves but interspersed with elements reaching into the higher and highest social strata. The “Roman Hellenism,” elevated beyond the ordinary thoughts and pursuits of paganism by the advanced Platonic philosophy represented by Seneca in the Roman capital, had become acquainted with the religious teachings of refined Judaism through the Alexandrian Bible and the writings of Philo. With or without the form of proselytism, it sympathized with Jewish monotheism and its purer moral teachings. This environment became the cradle of the first Christian community in the world’s capital. Just as the Oriental cults of all kinds found fertile ground in Rome—where, according to Tacitus’s bitter expression, “all atrocious and shameful things from everywhere flow together and are celebrated”—so too did Rome become a receptive field for the higher aspirations emanating from philosophy. These aspirations aimed to elevate humanity’s moral consciousness and bring the good and the beautiful closer to realization. Among the driving forces of this new outlook was the belief in the personal realization of the ideal in a living bearer of that ideal. This was parallel to the widespread contemporary religious belief in a helping and saving Savior, as propagated by the cults of Serapis and Asclepius. This belief naturally drew new strength and definition from the messianic prophecies during the study of the Old Testament. Everything was thus prepared, only waiting for the trigger to initiate the realization of these tendencies in a specific community.

(p. 377)

For Steck, that trigger was “the news of the Messiah’s appearance in the East”. (I wonder if a stronger case can be made for the trigger being related to the destruction of “Judaism’s” centre in the 66-70 CE war.)

This trigger would have been the news of the Messiah’s appearance in the East. Here, disregarding chronology, we can almost fully adopt the depiction given at the beginning of the Clementine Homilies. Clement, who had spent his youth in chastity and moderation, had fallen into deep sorrow over the tormenting questions about the origin and destiny of the world and humanity. He turned to philosophy but found no certainty in the conflicting teachings, especially regarding life after death. In this doubtful state, he became aware of news that reached Rome under Emperor Tiberius one spring and kept growing: as if an angel of God were traveling through the world, and God’s plan could no longer remain hidden, the news was that someone had risen in Judea and was preaching the eternal kingdom of God to the Jews, confirming his mission with signs and wonders. This news spread more and more, and already assemblies (συστήματα) were eagerly discussing who the newcomer was and what he wanted. In the autumn of the same year, an unknown man publicly proclaimed: “Men of Rome, hear, the Son of God has appeared in Judea and preaches eternal life to all who are willing to listen, if they act according to the will of the Father who sent him,” and so on. This account in the Clementine romance probably contains more truth than is generally attributed to it. This or a similar scenario must have occurred in the formation of the first Roman Christian community. The news of the Messiah’s appearance spread from the East, found fertile ground in the circles in Rome who were alienated from the world and pursued philosophical ideals, and formed a small Christian community from the Roman population. To this, individuals from the Jewish colony (like Aquila and Priscilla in Acts 18:2) and proselytes may have joined, without affecting the Gentile Christian character of the community. Thus, it would be somewhat like the Reformation—a dual origin of the new religious principle. On one hand, it arose in Palestine through the messianic movement originating from Jesus and his disciples. On the other hand, it was prepared by the development of pagan philosophy and religion in Rome to such an extent that the mere news of the Messiah’s appearance sufficed to bring it to life in the world capital, where it naturally took on a unique character from the beginning and retained it for a long time.

(pp 377ff)

I have been trying to think through how a similar scenario among Jews/Judeans was preparing the way for Christianity but Steck has added a balance to that perspective by reminding us of the evidence for the earliest Christian community in Rome being distinctively gentile in origin. There is certainly much to think through.

Even if this view can only initially present itself as a hypothesis, it is surely worthy of closer examination. At the very least, it easily explains how the Christian community in Rome, at the time Paul arrived, could already be an established and well-founded one, yet not be connected with the Jewish colony there. It then also explains the distinctly Gentile Christian character of the Roman Christian community from the outset, as assumed by the Epistle to the Romans and particularly evidenced by the findings in the catacombs. Moreover, this view sheds new light on the further development of Christianity. If Christianity emerged simultaneously in a dual form—one Jewish Christian and the other Gentile Christian—then this separate existence of the two centers, Jerusalem and Rome, could persist for a time. Eventually, however, as the Christian church continued to grow and unify, these two halves had to merge into one cohesive entity. The integration of the two halves, the Eastern and the Western, could not occur without a transformation process affecting both. The Jewish Christian communities of the East had to abandon their traditions, insofar as these had not already been disrupted by Paul’s activities, for their Christianity to be feasible within the greater church. Conversely, the Gentile Christian communities of the West had to accept certain customs and practices carried over from Judaism if they wished to join the closer fellowship with those communities. Notably, they could not reject a lifestyle aligned with the essential demands of Judaism, as prescribed for proselytes. This process was prefigured by Paul’s historical activities, which first established the connection between the two halves of the Christian population. Accordingly, the process could not unfold easily or naturally; resistance was inevitable on both sides, potentially leading to extremes that pushed the opposition to its peak. This painful but beneficial process of integration is testified by the literature of early Christianity, and specifically, the Pauline letters are symptomatic expressions of the resistance from the more liberal faction in the Roman community against attempts to Judaize them. From the Epistle to the Romans to the Epistle to the Galatians, this conflict escalates to its highest point before subsiding as the extreme demands of the Judaizers fail to prevail, while moderate ones gain acceptance.

(pp 379f)

Steck, Rudolf. Der Galaterbrief Nach Seiner Echtheit Untersucht Nebst Kritischen Bemerkungen Zu Den Paulinischen Hauptbriefen. Berlin: G. Reimer, 1888. http://archive.org/details/dergalaterbriefn0000stec.

English translation is available at The Epistle to the Galatians examined for its authenticity along with critical remarks on the main Pauline letters [PDF – 5 MB, on my vridar.info page]