Let’s imagine that oral traditions among today’s bedouin Arabs may be able to guide us in understanding how oral traditions worked in the days when the Bible stories were being originally told. — But don’t misunderstand. The Bible stories, even if they were originally sourced from pre-literate oral tales, have been artfully constructed to convey theological messages. But even the pre-literate oral traditions among Arab tribes have been re-written (sometimes for modern film) in ways that bear little resemblance to the themes of the original. What I am trying to imagine here is the evidence for the original biblical tales and how they compare with what we know of

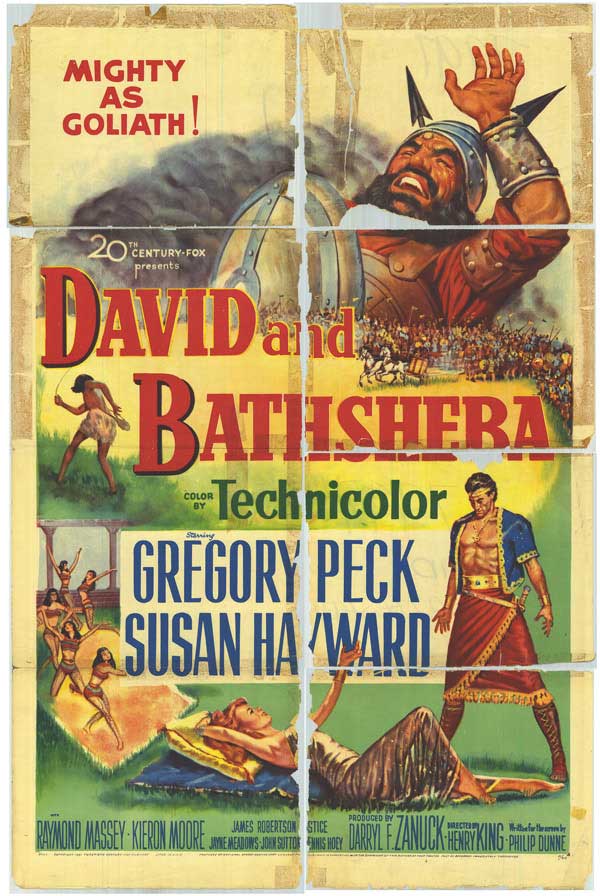

Let’s focus on one Bible story for exercise, the story of David, and compare its elements with what we know about story-telling among peoples with long traditions in the Middle East. Incidentally, let us ask how one can know if an oral tradition has any historical basis at all.

That’s what Eveline J. van der Steen did when she wrote “David as a Tribal Hero: Reshaping Oral Traditions”, a conference paper eventually published in Anthropology and the Bible: Critical Perspectives (edited by Emanuel Pfoh). (I’ve added my own little asides reflecting on potential relevance for what we read in the Gospels.)

That’s what Eveline J. van der Steen did when she wrote “David as a Tribal Hero: Reshaping Oral Traditions”, a conference paper eventually published in Anthropology and the Bible: Critical Perspectives (edited by Emanuel Pfoh). (I’ve added my own little asides reflecting on potential relevance for what we read in the Gospels.)

Arabs had and have a plethora of vernacular traditions: various forms of poetry, genealogies, epic legends and tribal histories. Oral traditions are a rich source of information, provided they are eventually written down and preserved. (p. 127)

And written down and preserved many have been since the 20th century when literacy pervaded a critical mass of the Arab world. Until then they relied entirely upon storytelling, citing and singing for their preservation.

One form of oral tradition that can be traced back to pre-Islamic times is the akhbar, “short stories, recounting the adventures and battles of the various bedouin tribes.” Again going back to pre-Islamic times story telling competitions were held among the various tribes.

.

Features of the stories

- Usually focused on one tribal hero

- Eventually grew into tribal heroic cycles

- Recited by professional storytellers

- Recited in desert tents and coffeehouses of towns and villages

- Told or chanted (often a mixture of both) in prose or rhyming prose, interspersed with poetry.

Every Arab knew parts of these stories: they were, and still are, part of the national culture. (p. 128)

Nineteenth century Orientalist Edward Lane described how storytellers would come into coffee houses in Cairo, recite and/or chant their stories about tribal heroes, then — at an appropriate cliff-hanger moment — stop for the evening to ensure an audience for the next day.

That way a story session could last well over a year.

The storyteller would develop the story as he went along, borrowing from his repertoire of other stories and formulas, adapting the story to the audience and situation. So the audience itself played a critical part in the development of the story:

they expressed their approval or disapproval, and discussed the story with the narrator. In town the stories reflected life in the town, in bedouin camps the context would be the camp. Only the main storylines, and the heroes remained the same. (p. 128) Continue reading “What Makes a Good Bible Story?”