This continues the little “It’s absurd to suggest that most historians have not considered the strongest case for mythicism” series inspired by the unbearable lightness of the wisdom of Professor James McGrath. The previous post saw how Professor Larry Hurtado’s source for the comprehensive rebuttal to all arguments mythicist, H.G. Wood’s Did Christ Really Live?, in reality explicitly points out to the reader that it is not a comprehensive rebuttal to all arguments mythicist. The next candidate for a publication having considered “the strongest case for mythicism” that I consider is A. D. Howell Smith’s Jesus Not a Myth (1942).

This continues the little “It’s absurd to suggest that most historians have not considered the strongest case for mythicism” series inspired by the unbearable lightness of the wisdom of Professor James McGrath. The previous post saw how Professor Larry Hurtado’s source for the comprehensive rebuttal to all arguments mythicist, H.G. Wood’s Did Christ Really Live?, in reality explicitly points out to the reader that it is not a comprehensive rebuttal to all arguments mythicist. The next candidate for a publication having considered “the strongest case for mythicism” that I consider is A. D. Howell Smith’s Jesus Not a Myth (1942).

Curiously I have not seen this book mentioned by any modern scholars who emphatically declare that mythicist arguments have long since been addressed and decisively demolished. This is curious because Howell Smith really does address the major mythicist arguments of his day. Similarly surprisingly few anti-mythicists today cite Schweitzer as having delivered the death-knell to mythicism. We will see an interesting similarity between ways S and H-S each argue their case for Jesus’s historicity.

I will save some of the details of Howell Smith’s arguments for my next post. Here I want only to introduce A. D. Howell Smith to those of us who only dimly recall my post on his Preface three years ago. I have reformatted it and added subheadings and bolding. Jesus Not a Myth was published in 1942, not long after the appearance of H. G. Wood’s title with the same purpose.

I conclude with a summary of the various Christ-myth views widely known at the time.

Something was sometimes different back then

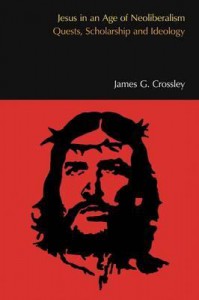

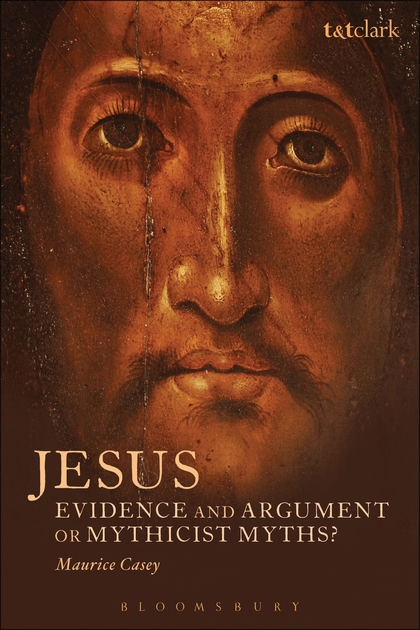

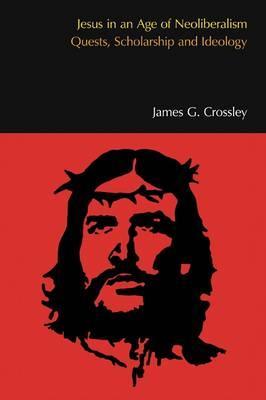

Notice the way our author actually has some positive things to say about the mythicists he is about to debate. It sounds surreal to read such things given our familiarity with the demonization and gratuitous insults we routinely expect from the McGraths, the Hurtados, the Caseys, the Hoffmanns etc. McGrath, Hurtado and Casey would have readers think mythicism is no more rational or informed than are flat-earthers or moon-landing hoaxers. Seventy years ago Howell Smith (along with Goguel and Wood and Schweitzer and other critics) actually acknowledged the rational spirit infusing mythicism and the names of several prominent and esteemed scholars and others who at the very least toyed with the plausibility of the Christ myth idea. Today’s critics — are there any exceptions? — are far more universally savage in their personal attacks and far more dogged in their refusal to allow any mythicist proposition to be accorded the faintest touch of rationality. Is this a sign of some desperation that the idea just won’t ever seem to go away? Or is it a symptom of the crudeness of an American-Christian dominated scholarship by contrast with the kind of religious ambience of Europe in an earlier generation?

Within perhaps the last twenty years the denial that Jesus ever existed has been changed from a paradox to almost a platitude for an increasing number of Rationalists, and occasionally a Christian of strong modernist leanings shows himself more or less sympathetic to it. Continue reading ““It is absurd to suggest. . . “: The Overlooked Critic of Mythicism (+ A Catalog of Early Mythicists and Their Critics)”