The plague of Athens is one of the most detailed, vivid and life-like accounts of any event from ancient times. The historian who penned it (Thucydides) assures all readers that he relied upon eyewitness reports and that he personally investigated what had happened in order to be sure of leaving a record that would be of use (as well as interest) to posterity.

But how historically true is it? Is it hyper-sceptical to even ask that question?

I ask because a few New Testament scholars who study Christian origins claim that those who raise doubts that the author of the two-part prologue to Luke and Acts was really relying upon eye-witness testimony as he appears to be claiming are “hyper-sceptical” and unreasonably biased against the Bible. This post is part of a series showing that such critical questions are indeed applied to works other than those in the Bible and that they are perfectly legitimate and gateways to deeper understanding of the texts.

Further, among ancient historians and classicists we find the rule that we can never be certain of the historicity of a narrative without external or independent corroboration. This, too, is another detail dismissed as “hyper-scepticism” among some New Testament scholars who have built “bedrock history” upon their biblical sources.

Before resuming with Woodman’s discussion of the way the historian Thucydides worked it’s worth pausing to consider an extract by Henry R. Immerwahr from the Cambridge History of Classical Literature:

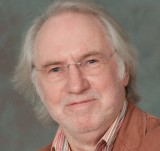

The close association of history and literature produced a distinctive manner of presentation which creates difficulties for anyone who tries to use the ancient historical works as source materials. Especially through the influence of epic and drama Herodotus and Thucydides set a style followed by almost all ancient historians, which may be called mimetic, that is, they write as if they had been present at the events they describe. (An exception is the Oxyrhynchus historian who aims at a more dispassionate narrative.)

When Herodotus describes the conversations between Gyges and Candaules or the feelings of Xerxes after Salamis we can hardly believe that this is based on evidence; it is rather an imaginative, ‘poetic’, reconstruction aiming at authenticity in an idealized sense.

The same is true of Thucydides when he supplies motives for actions by delving, so to speak, into the minds of the participants (e.g. the feelings of Cleon and the assembly in the discussion of Pylos, 4.27*1″.) without mentioning his informants.

The use of speeches is only the most obvious device of the mimetic method; it reaches into the smallest narrative details and tends to destroy the distinction between ‘fact’ and interpretation. This factor, more than any other, gives ancient historiography its unique character. (CHCL – pp. 456-7)

This post does not argue that there was no plague in Athens during the Peloponnesian War — although see the side box for the status of the evidence for its historicity.

What this post examines is Professor of Classics A.J. Woodman’s case for Thucydides having constructed a fictional scene based upon that apparently historical event. We will see the way “historical” writing was conceived in the Hellenistic, Roman and Jewish worlds in the Classical-Hellenistic-Roman eras.

I am focusing on Thucydides because he is generally considered the historian to be most like the moderns, taking scrupulous care to establish the certainty of any fact he writes, avoiding any mythical or miraculous tales, striving for an almost modern form of “scientific accuracy”. If it can be shown that this image of Thucydides’ work is accurate then we may indeed read ancient historical works in hopes of finding that others, too, have at least to some degree written the same way, especially those for whom we have evidence that they aspired to be compared with Thucydides in some way. Thinking specifically here of Josephus and the author of Luke-Acts.

This continues from my previous post on A.J. Woodman’s argument.

Continue reading “How Ancient Historians Constructed Dramatic Fiction: Thucydides and the Plague”